When news broke of the death of Larry Pitchford, known to wrestling fans as Beauregard or Beauregarde, it called to mind line that “Tough” Tony Borne had once told me about Beauregarde.

“He was different,” chuckled Borne, indicating he probably could have said more but chose not to. “A lot more guys are a lot more memorable around the Northwest here than what Beauregard was. You very seldom hear his name mentioned even when they talk of the oldtimers.”

It’s certainly the case when people talk about music and wrestling, currently having a resurgence of sorts with the talents of Joe Hendry especially.

But Pitchford’s story is pretty great, and his death on July 22, 2024, at age 85, from an undisclosed illness, at the Ellen Memorial Care Center in Honesdale, Pennsylvania, is worth retelling.

I mean, he once threatening the Easter Bunny on live TV!

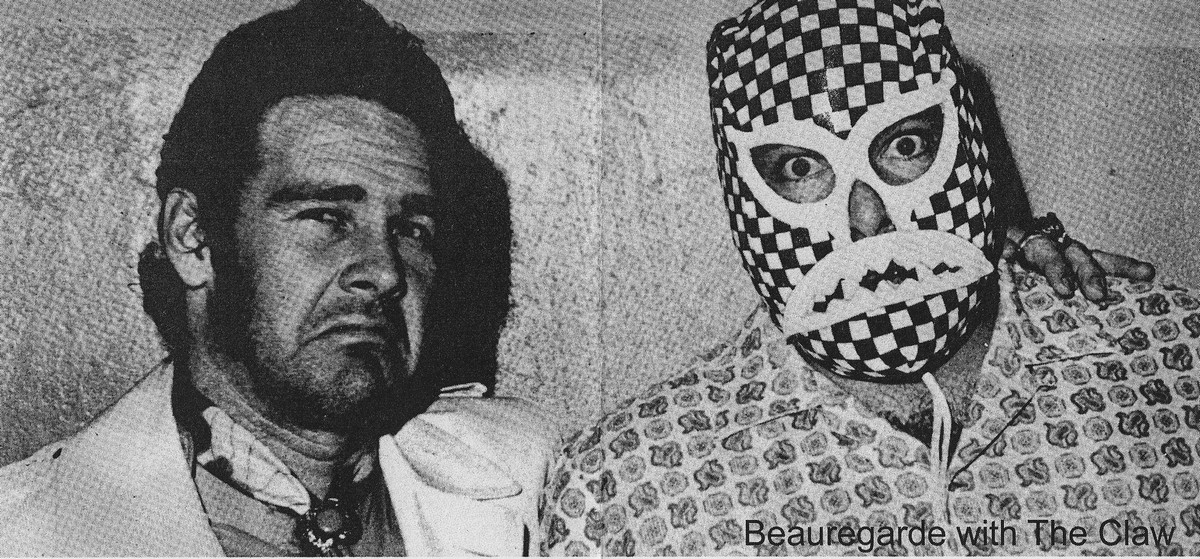

It was the night before Easter in 1970, and Beauregarde was on Portland, Oregon’s KPTV, telling viewers that he was going to let his evil minion, The Claw, loose in town. “All you kids out in TV land are not going to have any candy or Easter eggs tomorrow. I told The Claw to hide in the bushes tonight and wait for the Easter Bunny to come by, and when he does I told The Claw to jump out and put the claw hold on him and squeeze, and squeeze, and squeeze.”

Beauregarde and The Claw. Photo courtesy Larry Pitchford

The Claw was Tom Andrews under a mask, and he hadn’t been clued in on what Beauregarde was going to say. “I was just standing there. He was doing the interview. He came up with that, and I said, ‘Uh oh,'” said Andrews, who died in 2020.

Uh oh is right. The phone lines lit up, and the station representatives threatened to ban Portland Wrestling forever if an apology wasn’t made. “I laughed my butt off,” said Larry Pitchford, aka Beauregarde. “I had to come back on: ‘No, no, easy, I’ll keep him, I’ll cage him. I won’t let him kill the Easter Bunny.'”

That’s just one tale of the nasty vitriol spewed by Beauregarde during his 11-year career, spent mostly in Hawaii and the Pacific Northwest. Truthfully, he’s been almost forgotten by today’s fan, but he shouldn’t be. Beauregarde was a pioneer, both with his outfits and, more importantly, his music. At time when very few grapplers came to the ring with any music, Beauregarde came out to a song, “Testify”, that he wrote and recorded himself in 1970. Plus, he even made a music video for the song, with him mouthing the words to the song as he wandered through Portland, throwing change to winos.

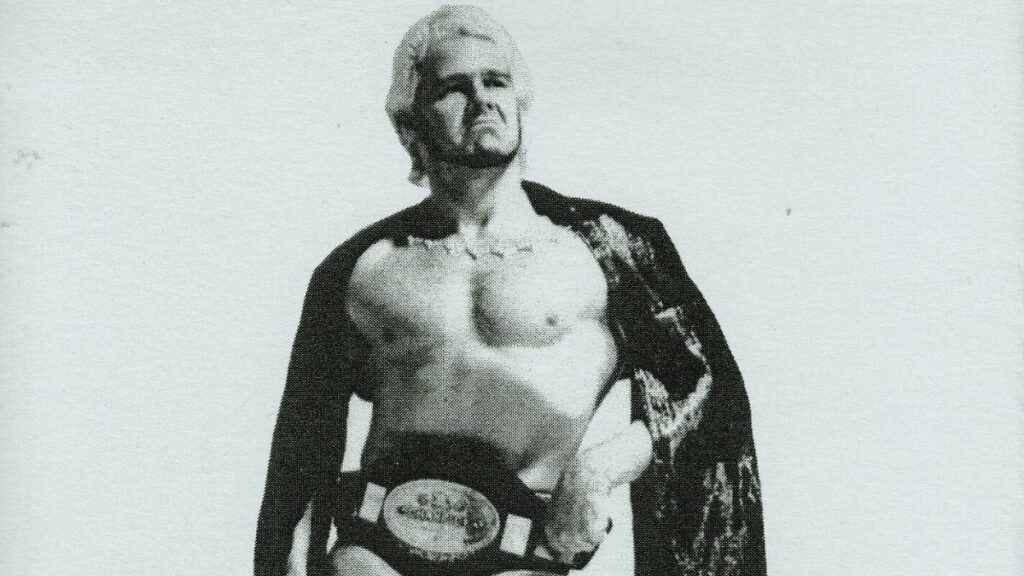

A promo for Beauregarde. Courtesy Larry Pitchford

Greg Sage of Zeno Records did more than anyone to keep Beauregarde’s memory alive. As a 17-year-old, he played on Beauregarde’s LP, and as an adult, he was able to reissue it as a CD. The first time he saw Beauregarde on TV as a teenager, Sage was transfixed. “He was doing an interview, and he had his face right in the camera, and so outlandish costume on … it was just hilarious. I was just glued to it,” Sage said. “He was so hilarious, and his insults so clever, I just started watching him.

The music called to Pitchford.

“I always did like music, all the time we were driving from town to town. I wrote a couple of poems. I’d make them up as I was thinking about them. Then I thought, ‘Hell, I could turn these into a song,'” explained Pitchford. The single of “Testify” became so popular in Portland that he was invited to record a full album. “I started the whole thing,” he said of the rock ‘n’ wrestling connection. “I was the first rock and roller, and the first guy to record an album, record it and sing it.”

Well, that could be debated, as music had long been used in pro wrestling, and even back to the 1950s, wrestlers like Sweet Daddy Siki and Frank Townsend were putting out singles.

It’s not like Pitchford planned it all out. Born April 29, 1939, in Lima, Ohio, he wasn’t a big wrestling fan. After high school, he and some buddies left for warmer climes, and eventually ended up in Hawaii and in the ROTC program at the University of Hawaii to avoid full draft notices. “I kept messing up with the Reserves, so they drafted me into the regular navy. I failed my physical, so they let me out,” Pitchford said in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels.

Spotted at Dean Higuichi‘s gym by Neff Maivia, Pitchford was offered a chance to give pro wrestling a try, as Maivia wanted to open up a new promotion in the Philippines. Pitchford became Eric the Golden Boy, and worked alongside Harry Fujiwara, Nick Bockwinkel and Ricky Hunter. The Philippines were a crazy place to start a new career. “You couldn’t get enough fans. Some of the places we went to, you flew to one of the islands where the airport was just a goddamn grassy runway. There weren’t even paved roads in the town we went to wrestle in. Oh, man, it was really breaking new territory,” Pitchford said. “So that folded. That was just a quick dry run, because we ran out of money and had to come back.”

Beauregarde and Ripper Collins. Photo courtesy Larry Pitchford

In Hawaii, Pitchford was paired up with Roy “Ripper” Collins, who had been working with the nickname “The Southern Rebel.”

“He used to pass out this Confederate money, little fake Confederate money, and it was signed by General Beauregarde,” said Pitchford. “Ripper looked at it and he said, ‘Beauregarde, that’s a good name.’ I said, ‘Aw, that’s a faggot name.’ He said, ‘Now wait a minute, listen to me. One name stays better with you than two names — Liberace, Donovan, Fabian.'”

Johnny Barend, Beauregarde and Ripper Collins. Photo courtesy Larry Pitchford

But Collins was right. As a part-time valet and part-time partner to the likes of Collins and “Handsome” Johnny Barend in Hawaii, Beauregarde got lots of screen time. The Hawaiian promotion was a popular stopping point for talent on its way to or from the Orient, and Beauregarde worked with many of the greats during the measly 10 shows or so a month. The rest of the time was spent on the beach. One of Beauregarde’s gimmicks would be to bring high school girls onto the TV show and show off the latest dance crazes. “I was young, nice body, good-looking. I could get girls any time,” he said.

There was a feud with Mr. Fuji in Hawaii. The memory brought laughter. “He was crazy. Oh yeah, he was always crazy. Hee hee hee. Sneaky little Japanese guy. Harry, he was funny. I liked Harry,” said Pitchford, launching into a story:

Me and Fuji were doing a thing like we were going to fight each other, and building up to a big match. I got the idea for a song, “Fuji, stoogey, Fuji stoogey.” I just took little things and made up little songs. I’d play them on my interviews. “These boots are made for walking, and they’ll kick the shit right out of you.” I started doing that, and got me thinking when I went into Oregon, “Well, hell, I’ll just make some records.” It’s funny, the way things happen, the sequence that makes things happen.”

Pitchford had learned that being a wrestler was akin to being a salesman: “What you’re selling, is you’re selling yourself. So you’ve got to be able to make the people believe what you want them to believe, whether you want them to like you, you want them to hate you, or you want them to think you’re a prick. It’s like a salesman trying to sell a car. What the wrestlers do is they’re selling themselves to the public. The better you can sell yourself, the more money you can make.”

In Portland, the Beauregarde character really took off. “The thing that got me over so good in Portland was I got on TV and I told everybody that I was related to all the greatest people in the world. I went down to the theatrical place there, and every week, I’d rent a new outfit” — as Cleopatra, as the Pope, as Marc Antony, Julius Caesar, Al Capone, Hell’s Angel, the Caveman, Nathan Hale — “Every week, I would rent a costume and tell everybody I was related to that person.” Beauregarde would wear the same outfit for all the spot shows that week, then hand the bill to Don Owen.

“Beauregarde was a nifty little heat-generating machine during his stay here,” said Dutch Savage, a former tag partner in Oregon.

The surfboard finisher — a reverse double armbar, where he put their head between his legs and grabbed both arms and pulled them back up, so they would level — started in Oregon. But it didn’t work especially well in the non-surf hotspot. “That didn’t really get over, so that’s when I switched to the thumb, because the thumb was a lot more devastating, and we got a lot more out of it,” said Pitchford.

Beware the thumb. “I would always walk around and hide my thumb behind my back. People would say, ‘Referee, referee, he’s got his thumb.’ I would put my hand behind my back and stick my thumb out, just straight out, like I was getting ready to use it, I’d cock it. I’d say, ‘Yeah, I’ve got my thumb. It’s on my fucking thumb.'”

In one angle with Lonnie Mayne, his former partner, Beauregarde’s thumb was “broken” in the turnbuckle. “Then I had to wear a cast on it. That even got over a lot more because here I had this fake cast on my thumb that was sticking out three inches — then it was really a lethal weapon,” Pitchford recalled.

“Beau was a lot of fun even though we didn’t associate too much outside of wrestling. We stayed at the same place and he was sort of a legend there. He had his room all painted up with the psychedelic stuff,” Roger Kirby told Ring Around the Northwest. “He was single and he had a waiting list to get in to see him as far as the girls were concerned. He was a fun guy to be around.”

Nick Kozak recalled the women around Pitchford, telling Ring around the Northwest, “He was a hell of a manager. He was kind of green but he picked it up real quick. We were in Park Haviland. The guy who owned the motel was a wrestling fan. Top of the Park with a swimming pool. We got to be pretty friendly and the girls coming around, it got to be pretty lucrative. Beauregarde had his room done in leopard skin.”

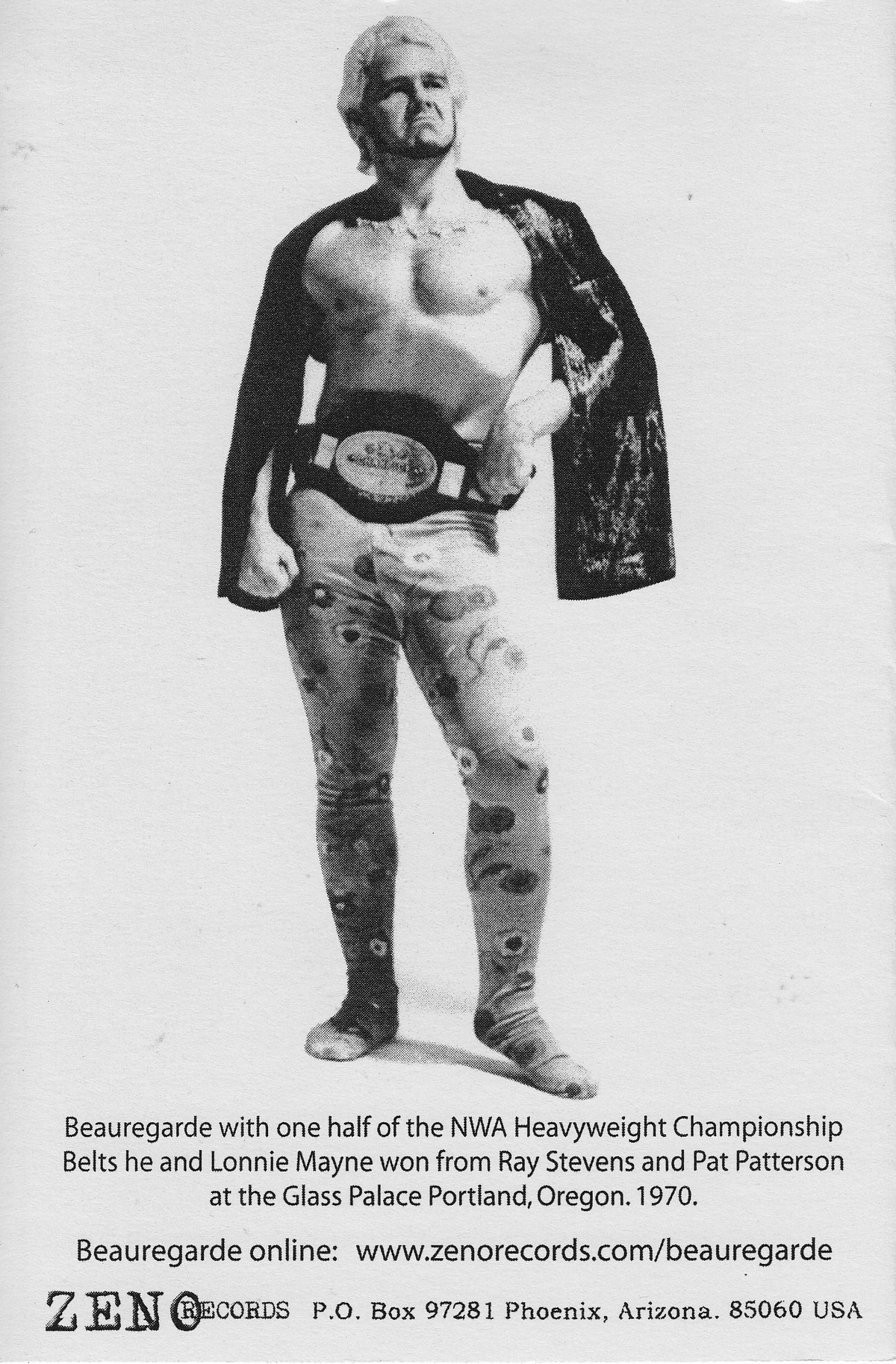

Beauregarde the singer. Photos courtesy zenorecords.com

But when the 5-foot-9, 200-pound Beauregarde left Portland, whether it was Australia, Arizona, North Carolina, Japan, or California, it wasn’t the same, and he wasn’t a main eventer. As time went on, he was dwarfed by the newer generation of wrestlers. “Everybody kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger. I wasn’t that big. I had to wrestle Ernie Ladd a lot. Shit, Ernie was 6’9″, 320. So when the guy’s 100 pounds heavier and a foot taller, it’s just not believable,” Pitchford said.

“After you’re in a territory for three years, four years, wrestling on the opening match getting beat every night, they just can’t use you no more. You’re all used up,” Pitchford said.

A short-lived marriage brought him to Florida, where he helped run a few towns for Eddie Graham’s promotion. “I would just go to the arenas and bring them the card for next week, pick up the receipts and the money, and I had all the finishes. He sent me a tape that all the matches on it, how they were going to go, what the finish holds were going to be, how he wanted them to go into them, and who was going to do what. I was the coordinator,” explained Pitchford. That included theme music, taping the cassette tapes to the voice booth to get played when, say, Dusty Rhodes or Dick Slater, walked to the ring.

Pitchford worked construction and wrestled three nights a week, and saved up enough money for a nice condo on the ocean. He ran a drywall and sheet rock business for years, saved his money, and enjoyed fishing every day.

There were no fan fest appearances or reunions for Pitchford.

Still in the conversations with this writer, he was more than content with the way things worked out: “It was fun. I loved it.”

The funeral arrangements were private, and the obituary listed survivors as his “friend and caretaker Robert Zabady, RN and his wife Terry of Hamlin and countless friends and admirers.”

— with files from Steven Johnson