Though extremely well respected by his peers in the wrestling business and widely acknowledged as one of the top shooters of his era, Winnipeg-born wrestler George Gordienko isn’t widely remembered by North American wrestling fans of the current age. Because he spent the majority of his career overseas—based for many years in England but a frequent traveller to numerous countries around the world—Gordienko was never a household name to the majority of North American fans even during the height of his outstanding career. That would have changed dramatically, however, had Lou Thesz managed to get his way in the mid-1950s.

The first meeting between Thesz and Gordienko appears to have taken place on March 5, 1948, when both appeared on a show in Buffalo. At the time, Thesz was a major star who would capture his first National Wrestling Alliance world heavyweight title the following year, and Gordienko was a 20-year-old phenom believed by many to be on his way to the top among wrestlers in the United States and Canada. But then, just a few months after meeting Thesz, Gordienko was out of wrestling entirely.

The next four years, from 1948-1952, represent a pivotal and somewhat mysterious time in the life of George Gordienko. The short account of those years is that he attended the University of Minnesota; dipped his feet in organized Communism; got married; left university and worked at a flour mill; decided to leave the United States when he seemed to be on the authorities’ radar for his Communist connection; returned to Winnipeg with his wife and their young son; worked at odd jobs in Winnipeg both before and after the breakup of his marriage in 1951; got barred from reentering the United States; moved to British Columbia and spent about a year working on a log boom; and got a phone call from Stu Hart in the summer of 1952, asking whether he’d like to get back into wrestling.

Gordienko answered affirmatively and made a successful comeback after four years out of the ring, establishing himself as a top contender in Stu Hart’s Big Time Wrestling (later Stampede Wrestling). From the time of his return to the ring in the fall of 1952, Gordienko performed exceptionally well, losing few matches and impressing fans and fellow wrestlers with his Olympic-caliber power and grappling skills. When Thesz came through the territory in the spring of 1953 to defend the NWA title against the top contenders in the Prairies, Gordienko came out on the losing end of his first challenge for a world title—on May 26, 1953, before 3,000 fans at Edmonton’s Sales Pavilion—but clearly made a big impression on the man who, over the course of his amazing career, would hold the NWA world heavyweight title more than twice as long as anyone else.

Gordienko continued to excel in the Alberta-Saskatchewan circuit until the following spring, when he had the opportunity to wrestle for several months in Australia. Although he was expected to return to Western Canada when his Australian tour ended in August 1954, Gordienko decided instead to board a liner for Naples, Italy, and to spend several months in Europe travelling and attending art school. He didn’t wrestle during that stay—his first of many—in Europe.

When his money was running out, Gordienko crossed the Atlantic by sea and returned to Canada, and by the early spring of 1955 he was back in Alberta working for Big Time Wrestling. Positioned strongly from his first night back in the promotion, Gordienko ran off a series of impressive victories before being rewarded with his second-ever chance to face Lou Thesz for the National Wrestling Alliance Heavyweight title. The first time they met—in Edmonton on May 26, 1953—Gordienko had lost cleanly to Thesz. Their second career meeting—also in Edmonton, exactly 23 months after their first matchup and just four weeks after Gordienko’s return to the ring following his excursion around the world—ended in a time-limit draw.

Two days later, in Regina on April 28, 1955, Thesz and Gordienko fought to a no-contest. From there, Gordienko went on a tear and put himself first in line to challenge Thesz again when the NWA Heavyweight champion came back through the territory two months later. By then recognized as the Canadian Heavyweight champion by virtue of a June 13, 1955, victory over Earl McCready, Gordienko lost his NWA title challenge the following week but, by all accounts, continued to impress Thesz with his skill set, professionalism, conditioning, and sheer power. In an endnote in Thesz’ autobiography Hooker, Thesz’ coauthor Kit Bauman writes, “Thesz and Gordienko first met in the early 1950s when Gordienko was working for Calgary promoter Stu Hart—a famous shooter who rated Gordienko as one of the three toughest men he had ever seen—and were twice booked together in Edmonton [in 1955]. Thesz was so impressed [and said,] ‘We once worked a 60-minute draw [on April 26, 1955], and I couldn’t run him out of gas, which almost never happened.”

The grind of travelling from territory to territory to defend the National Wrestling Alliance Heavyweight title often became an ordeal for Thesz and many of the NWA champions who succeeded him. Usually within a couple of years, champions, living out of hotels and often not getting home for weeks or even months at a time, were ready to work with the alliance to ensure a smooth transition to a new world champion who’d become the face of the alliance and tour the territories until he was ready to step aside or NWA directors and promoters decided it was time for a change.

With the champion’s body on the line in the ring night after night, it was considered wise, when possible, to have a substitute champion groomed or waiting in the wings in case a quick title change had to be made. NWA promoters were often in disagreement over who that designee should be, and they often backed wrestlers who’d been working for them, hoping some of the prestige and money associated with the NWA title might rub off on their home territories. While final say on who’d be the next NWA champion was out of the current champion’s hands, NWA directors and promoters listened very carefully to a champion who’d represented the alliance well and earned substantial respect and goodwill inside and outside the professional wrestling community.

By any measure, Lou Thesz—National Wrestling Alliance titleholder for about six years before dropping the title to Whipper Billy Watson, via countout, in Toronto on March 15, 1956—was such a champion.

But Watson wasn’t Thesz’ first choice to succeed him as the NWA titleholder. While Watson had enjoyed great success over the course of a 20-year career going into his 1956 NWA title shot in Toronto—where he was already a legendary wrestler—he wasn’t a grappler that Thesz, known as a tough critic of fellow wrestlers, held in high regard.

Wrestling historian J Michael Kenyon, editor of the updated Crowbar Press edition of Hooker (based on Thesz’ original 1994 bound manuscript edition), told George Gordienko’s nephew Ted Gordienko in 2010, “There were only a handful of wrestlers that Thesz put in that category of guys who were somewhere on a plane close to him. … George Gordienko was one of those guys he would put practically on an even plane.”

Thesz’ respect for Gordienko, of course, had grown out of their encounters in Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1953 and 1955. Kenyon said, “[Thesz] had some good 60- and 90-minute tussles with Gordienko, and Thesz would not go 60 or 90 minutes with anybody unless they were either a great performer like a Buddy Rogers [or a great] wrestler like a Luther Lindsay or a George Gordienko … those kinds of guys.”

Koji Miyamoto, another noted wrestling historian but one who had a close association with Thesz and managed his affairs in Japan for many years, notes, as far as Thesz’ plan to drop the NWA World Heavyweight title for a time in the mid-1950s was concerned, “[Thesz] mentioned to me that the [desired] successor was Gordienko.” Following his series of matches with Gordienko in the Canadian Prairie provinces—well before he suffered a skiing accident in 1956 and had to pass the title to his successor quickly—Thesz, according to Miyamoto, told Gordienko, “Come to the United States. I’ll let you be champion.”

But Gordienko’s exclusion from the United States was still in effect, and any hope of his having a run with the NWA world title rested on the willingness of American authorities to review his case and grant him a visa to wrestle in the United States. Though only a few years had passed since Gordienko had been deemed inadmissible to the US, Miyamoto says Gordienko, backed by key players such as Thesz and NWA president Sam Muchnick, filed a visa application which was rejected.

In an endnote in Hooker, Lou Thesz is quoted: “George was a salty dude, one of the best I ever saw, and it’s a shame we couldn’t get him into the country. … That was during the McCarthy era, though, and it just wasn’t going to happen.”

Regarding the quick NWA title change on March 15, 1956, following Thesz’ skiing injury, Miyamoto says Thesz agreed to drop the title to Watson in Toronto as a favor to local promoter Frank Tunney. “He liked Frank Tunney very, very much,” Miyamoto says.

While Watson isn’t generally remembered as a first-tier NWA champion, his title reign certainly helped boost business in Tunney’s Southern Ontario-based circuit, as about a third of Watson’s 120 or so NWA title defenses, prior to his dropping the title back to Thesz in St. Louis on Nov. 9, 1956, took place in the Tunney loop. Tunney also owned a share of the St. Louis promotion in 1956 and throughout much of his promotional career, and Watson had a successful series of title matches in that city as well.

It can only be speculated how a Gordienko NWA title reign might have stacked up against Watson’s, but Gordienko’s years of stadium-filling success around the world strongly suggest it would have stacked up well. Seemingly beyond debate, however, is that a Gordienko NWA title run would have cemented Gordienko’s legacy to wrestling fans, past and present, across the United States and Canada … if only Lou Thesz had gotten his way.

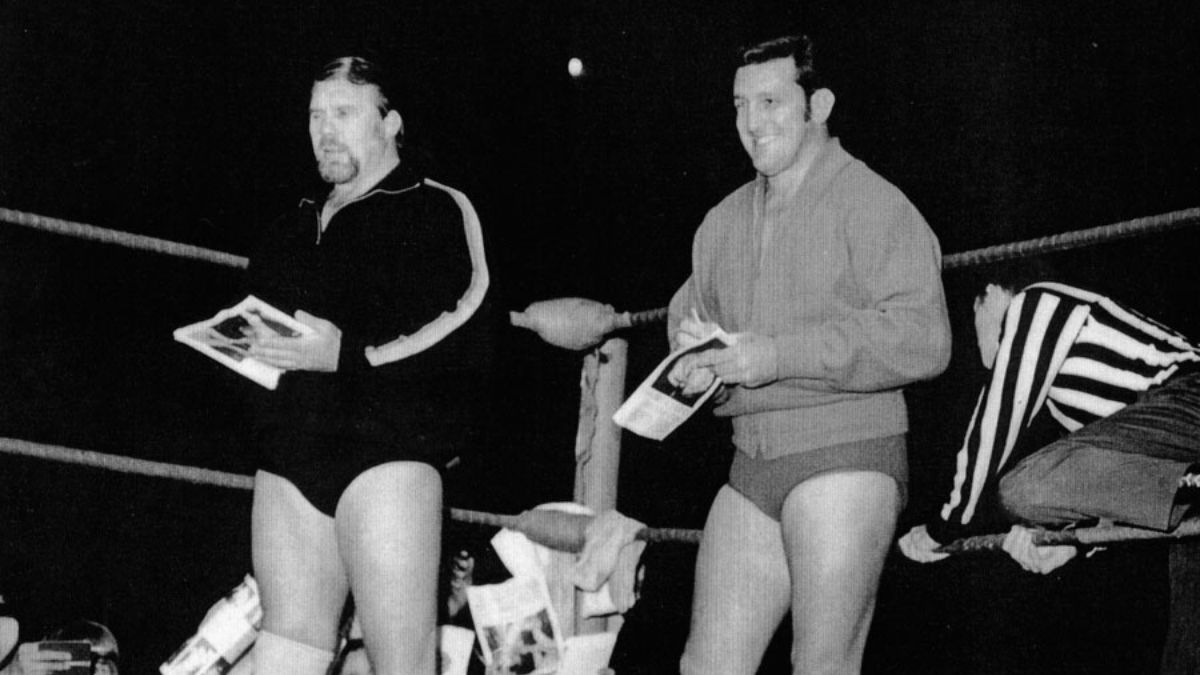

TOP PHOTO: George Gordienko and Billy Robinson. Chris Swisher Collection.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Watch for more from Steve Verrier previewing his George Gordienko biography in the coming weeks. Steve Verrier has also contributed in the past to SlamWrestling.net.

RELATED LINKS

- Dec. 20, 2022: George Gordienko finally has his day with great biography

- Apr. 25, 2022: Gordienko was destined to be an artist

- Jan. 10, 2022: Gordienko: Canada’s top wrestler worldwide from the 1950s-1970s

- May 12, 2004: Nephew aims to boost Gordienko’s legacy

- Buy George Gordienko: Canadian Wrestler, Artist and Renaissance Man at Amazon.com or Amazon.ca