Fritz von Goering, who died at the age of 94 on August 13, 2024 from heart failure, could be cantankerous both in the ring and out of it.

Just days after the long feature that was run on this site in 2009, written by Steven Johnson — For von Goering, a long journey to Hall of Fame — von Goering sent in an email:

Over the years Slam probably never said more than 2 words about me if they said any.

That’s ok as anything you would say would mean shit to me.

I never kissed ass with any one in wrestling or any goddamn reporter including slam or promoters.

I did like the few 3 short lines you wrote about me as you probably were forced to say because the wrestling Hall of Fame in Iowa inducted me.

Bottom line is fuck you – do not mention my my name on your web site.

Fritz von Goering

Yet two years later, he was on the phone with this author, sharing stories like nothing ever happened.

Like in the ring, you never knew what von Goering you’d get.

Noted columnist Bob Greene wrote about von Goering over the years. In 1978, Greene penned a sweet column praising memories of “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers, where von Goering came up, and in 1985, as wrestling hit mainstream heights, Greene recalled seeing Fritz around Chicago:

Fritz Von Goering was an alleged Nazi whose hometown was always announced as Berlin, but who in actuality lived above a bar over on Town Street and could often be seen shopping at the Lazarus department store.

Then in a CNN.com article in September 2010, Greene outed von Goering — for being on Facebook. “Fritz von Goering on a social network … something just seems wrong. He always seemed to be the most anti-social human being on the face of the Earth,” wrote Greene.

In short, von Goering may not have been a huge, nationally known wrestling name, but he knew how to make an impression.

As the late Seattle promoter Dean Silverstone once wrote in an email, “Fritz von Goering is quite a unique individual.” Silverstone had annual wrestler reunions at his home outside of town. “He really enjoys himself in Issaquah and we all enjoy hearing his stories. His been here maybe ten times and never told the same story twice.”

With that in mind, much of the story of Fritz von Goering is told in Johnson’s 2009 story, how he was a Chicago boy who fell into the wrestling game.

But the obituary, published on August 23, 2024, introduces a number of new details:

– Real name Harold Ray Jennings (Hal) (It had been reported to be John Gabor and Eric Pederson; there are legal documents where he is John Gabor, further complicating issues.)

– Born at UC Hospital, San Francisco, California, on March 31, 1930, of adopted parents Floyd and Lela Jennings. (It had been reported that he was born in 1928.)

– “After finishing high school and some college, Hal enlisted with the California National Guard at San Mateo while working as a draftsman for Ceco Steel in San Francisco. He completed three years with the California National Guard and transferred to the US Air Force as a Surgical Orderly in the 99th Medical Group. Hal was sent overseas to Great Britain and was stationed with the Royal Air Force for two years and eight days. One day he had a coke with Princess Elizabeth while she visited the troops.”

– While enlisted overseas, he developed a love for performing.

In the 2011 interview, von Goering went in depth on his training with Joe Pazandak. Three of them lived with Pazandak: George Gordienko, Pat O’Connor and von Goering.

Fritz von Goering and Jason Sanderson in 2008 at the Tragos/Thesz Hall of Fame induction. Photo by Greg Oliver

“We lived with him for a while, while we were being trained. I had to work my contract off with Joe, heh, heh, so that meant getting up every morning at six o’clock and we were mixing concrete in a wheelbarrow the old, hard way with a hoe. We worked from six to 12 every day, and then we trained,” said von Goering. The concrete was poured around the house, as Pazandak was improving his home out in the country outside of Minneapolis.

von Goering was on a different deal than Gordienko and O’Connor. He said that Tony Stecher paid Pazandak to train Gordienko, and O’Connor had already paid off his contract.

The training “was rough. He didn’t pull any punches, he didn’t hold back. Like, let’s go for a walk down to the end of the road with 300 pounds on your shoulders — try that with a 300-pound weight. I remember that was tough. But if you did it, then he’d ease off on you.”

Pazandak didn’t have mats set up—they’d go to the Y in town for that aspect of training. It was mainly about getting stronger. “He believed in physical endurance, was his gimmick, endurance. When the other guy’s breathing hard, you’ve got to win the match. If he runs out of gas, it’s all over.”

There was a mat in the garage, though, for some simple demonstrations.

The main takeaway from the wrestling-specific training was “how to protect myself when I fall,” said von Goering. “You always protect your head, and your lower back if possible. Try to take all the pressure on your feet or toes, and your shoulders.”

San Bernadino, California, May 17, 1958.

Pazandak reputation brought out lots of people to learn, but there were really just Gordienko, O’Connor and von Goering that were his true pupils. “He worked out with a lot of guys, he’d push around with them. But the three of us, he trained, put special time with. It was good. I don’t regret it.”

While Pazandak was his main trainer, von Goering noted others that helped along the way. Larry Hennig helped a bit around Minnesota, and then there was Ben Northrup, an Olympic amateur wrestler, when they were both in San Francisco, and “Judo” Gene LeBell in L.A.

von Goering had a successful career, but for whatever reason, never made it to the truly national consciousness of storied villains.

Therefore, when he began showing up at events like the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion or the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Hall of Fame in Iowa, fans and historians alike had to scramble to catch up on his career.

San Bernadino, California, May 3, 1958.

von Goering was a long-time resident of Campbell, California, where he lived with his wife, Kay. Eight years his junior, they had been married more than 50 years. Kay Gabor bred, raised and sold show dogs, especially poodles.

In 2018 von Goering, under his real name of John Gabor, and his wife Kay sued Rebecca Harris, Kristin Humphrey and Miriam Dreshler. The Defendants (a married couple and their mother/mother-in-law) were principles at a trust company and gave seminars to the public about financial and estate planning. The defendants recommended that the Gabors place their assets into a trust. Throughout the 1990s they established a series of trust for the Gabors’ assets overseen by the Defendants. Over time the Gabors had deposited almost all of their assets into these trusts. While the Defendants repeatedly assured the Gabors that their money was safe, between 2005 and 2012 they allegedly stole almost all of the Gabors’ money by transferring it into other trusts they held for their own benefit, on real estate schemes or most brazenly through a series of cashier’s cheques. Amid considerable procedural wrangling, the Gabors were eventually able to recover most of their money, when the Court created a constructive trust “to include all assets traceable” to the funds taken by the Defendants.

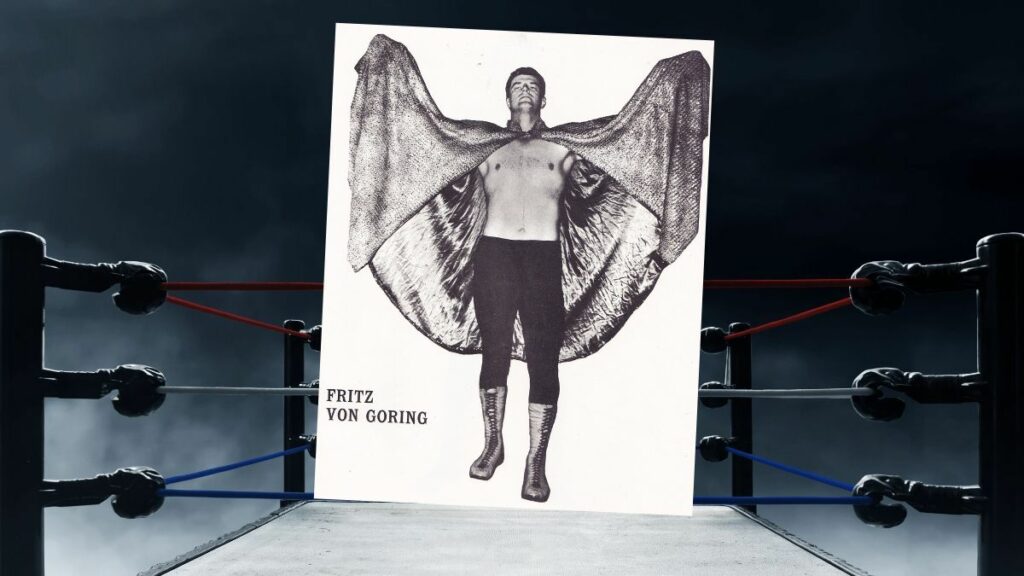

Fritz von Goering in 1964.

von Goering had been largely out of the wrestling-related spotlight over the last number of years.

He is survived by his wife of 63 years, Kay, who reached out to Lou Thesz’s widow, Charlie, to share the news of Fritz’s passing. His children were: daughter Joy (Marc) Strahm, daughter Linda (deceased) and her spouse Patrick Wright; son John Christopher Gabor. His grandchildren are: Stephanie (Rich) Horner, Robert (Beth) Hartmann; plus four great-granddaughters and twin great-great-grandsons.

There will be a private military burial service for family and friends.

— with files from Steve Johnson

RELATED LINK