Before we get to the garlic-eating, the power of the mustache, and the non-Turkish origins of the Ali Bey with roots in Canada who could speak seven languages, we need to establish that there were, in fact, more than one Ali Bey … or a variation thereof. It’s almost like being promoted as a Turk meant you had to use the name.

Koca Yusuf / Yousouff set the standard for all Turkish wrestlers, becoming The Terrible Turk, perhaps the first real, true gimmick wrestler in the late 1800s. Many followed after he died in 1898.

Some others: Hassan Nuhammed was another The Terrible Turk; Rick Miller was just The Turk; Oscar Mollinar worked in the early 1980s as Turk Ali Bey; Ali Ahmet Capraz primarily wrestled abroad in the 1950s as Ali Bey or Hassan Ali Bey, including in England, Australia, and New Zealand, but was usually billed from Egypt; Bairam Bey was also Pasha Bairam Bey and Pasha Bey; Robert Manoogian, aka Bobby Managoff Sr., was even another Terrible Turk; who was the Ali Bey in 1939 in Arizona, or the Hassan Ali Bey in Ontario and Quebec in 1954?; there’s a Mohamed Ali Bey in 1962, then gone. Or Google Tito Kopa, and at first glance, he is a dead-ringer for our subject, and Kopa worked as Hassan Bey. As one might guess, it’s a bit of a mess out there if you search just “Ali Bey,” with many sites confused about who was who.

With this piece, we will be setting the record straight on Ali Bey, born Georgios Stefanides in April 1912 to Cosmas and Sofia Stefanides, who lived near Sparta, Greece; he later was a referee in southern Ontario, known as George Kanelis.

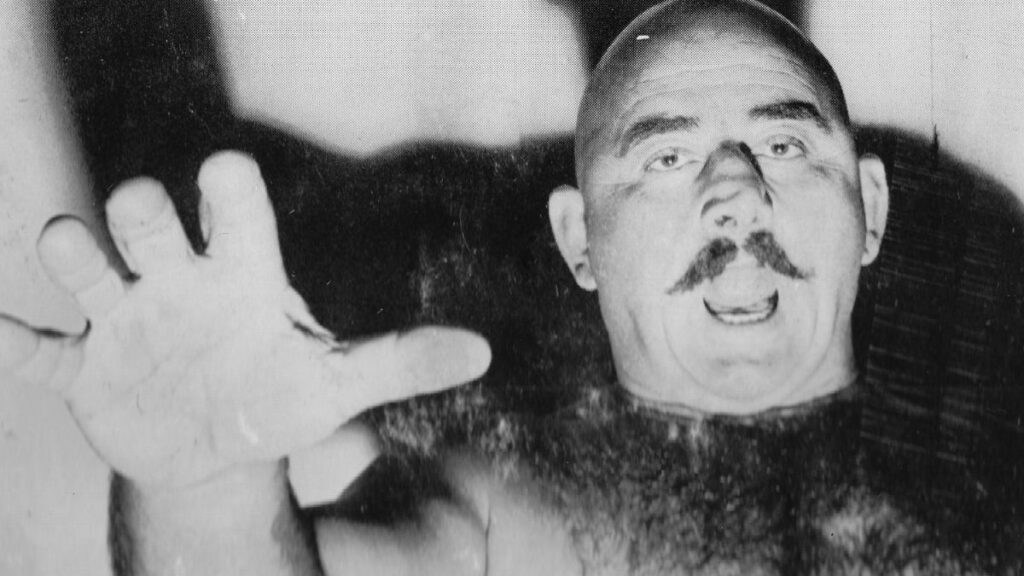

That’s George Kanelis as the referee as action takes place in Maple Leaf Gardens. Photo by Roger Baker

* * *

Georgios Stefanides grew up with brothers Michael, Gus and Alex, and a sister, Sofia, so it’s a fair assumption that there was some roughhousing going on.

How much truth was there to the oft-told origin story of Ali Bey?

Ali is an honest to goodness Turk, hailing from Sumsunda, Turkey, which is a small fishing village on the Black Sea. As a youth and a young man, Ali was a fisherman, same as his forefathers. It was one day after his fishing chores were done that Ali accidentally became a wrestler. Some Turkish amateur champions were working out in the sand and needed partners for a good workout, they invited the boy to take part. He not only took part, but took the champs apart. From that day on it was no more fishing for Ali Bey.

Probably none, but it’s a cute tale.

At some point, Georgios became interested in Greco-Roman wrestling. The family was led to believe that he competed in the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, but he did not.

World War II was tough on Greece, and the Stefanides family separated, going their different ways. Siblings Michael and Sofia ended up in Australia, and Georgios didn’t reconnect with them for decades.

Georgios himself arrived at Ellis Island, in New York City, on November 18, 1937, via the S.S. Conte Di Savoia, sailing from Naples, taking seven days across the Atlantic, and he worked on the ship for passage shoveling coal in the steam room — a job he had done for a few years previously on various merchant ships.

But it wasn’t the first trip to North America for Stefanides. In 1932, he arrived in Halifax via a merchant ship, but then hopped the border and made his way to Chicago. Stefanides excelled at running card games, working in some of the less-than-legal casinos. When officials caught up with him, and he had no papers, he was deported back to Greece, waiting five years to try again.

The family doesn’t know much about what Georgios did immediately after arriving in New York in 1937, other than he got into wrestling.

What they do know is that Georgios met Diamantina Santrizos, of Montreal, and they married in 1942. Under their Anglicized names, George and Diamond, had six children: Sophia, Connie, John, Kathy, Angie, Andy.

Consistent with the life of a traveling wrestler, the children were born across North America: three in Montreal, two in Texas, the last in Ohio. Diamond stayed home as the homemaker, no matter where they lived.

Andy Stefanides is the youngest and the most passionate about his father’s wrestling legacy. “We were always on the road in different states. The majority of time we were in Ohio living, but we lived in Texas, South Carolina, New Mexico, but majority of it was in Ohio,” he told SlamWrestling.net.

However, Andy missed out on his father’s active wrestling career, instead only getting to see him as a referee in and around Toronto, where the family settled in the late 1960s.

He has lived vicariously through the stories handed down to him from the rest of his family. “In the summer time, some of them would go with him a week here or there with wrestling. They would travel with him when he was working locally,” noted Andy.

The exception was their brother, John, who had been diagnosed with Cerebral palsy.

“My brother didn’t go to school,” said Andy, “so he was mostly with my dad, and the wrestlers, always, traveling throughout the year with him.”

The wrestlers all looked out for John, and Papa George became obsessed with keeping the Cerebral palsy at bay. “They worked [with] him and did all the stretching and all the moves in Arizona, the salts and the mud baths and that. My brother became what he was, he was able to walk and talk and everything. Nothing was wrong with him. You couldn’t even tell that my brother had Cerebral palsy, because over those years, he was always with him, working where they were wrestling,” said Andy.

Now, the wrestlers may have looked out for John, but that doesn’t mean they smartened him up to the inner workings of the wrestling business. “There were stories where my brother took it a little too serious because he didn’t know that the guy wasn’t hurting him, but the old man got hit in the head and got cracked and was bleeding,” said Andy. “And there was a story where my brother jumped in the ring and a couple of other wrestlers had to go get him because he was beating up the other guy with a chair. He didn’t know between the right and the wrong at some points.” (John passed away in 2015.)

Usually, the family had a pet budgie — so the bird came on the summer treks too.

* * *

The thing with looking back at the in-ring career of George Stefanides / Georgios Kanels / Ali Bey / Alli Bey / Hassan Bey / Hassan Ali Bey / Abdullah Bey (and other variations) is that he was both a villain and a hero, his natural charisma often transforming him during a run in a territory into one of their own, someone to be cheered. Coming in at only 5-foot-5, with a pot-belly, he was more common man than many of his peers.

A 1955 Tucson Citizen description was as visual as words can be: “Ali, better known as the Turkish Delight, is another crowd pleaser, with his zany tactics, one of which is bouncing like a rubber ball when he gets hit.”

One undated, unidentifiable program from the family scrapbook tried to explain the appeal:

For a stocky man … weighing 216 … Ali darts around like greased lightning to the consternation of many an opponent. He never stops moving once he climbs between the ropes into the squared circle.

Fans find him tremendously colorful, even though they don’t always approve of his antics in the ring.

Ali Bey is one of those amazing fellows who can wallop his opponent between the eyes during a scrap and then step out of the ring and calmly discuss it with the fans in at least six languages.

Another undated Stampede Wrestling program wrote something similar:

A short stocky guy, he is something of an enigma to most fans.

He uses villainous tactics on occasion, yet somehow frequently makes the audience like him. He has been good for plenty of laughs, yet is too effective to be rated as just a clown.

That’s his main beef.

“You laugh at me. You think I am no good because I am little guy,” he has declared. “But I am good little guy. I am yet to be beaten. I am tough Ali Bey and nobody yet is man enough to prove I am anything but first rate.”

His father was indeed a polyglot, said Andy. “My dad had a Grade 3 education but he could speak six languages from traveling all over the world.” Then he listed the languages — Greek, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Ukrainian, English — and realized it added up to seven. That could be used for storyline too. In a Stampede Wrestling program, from Regina, Saskatchewan, on September 18, 1950, there were questions: “Prior to (his) match, there was some doubt as to whether or not Ali Bey could speak English. He was said to be fresh from his native Istanbul. But somehow the big groaner has picked up a few words here and there. ‘Me, I hail from Buffalo,’ he announced, without a trace of any accent, a few moments before he left the dressing room.”

As for the look itself, in his early matches, under his real name, George Stefanides has black, curly hair. Then, in 1950, he arrived upon the gimmick he’d use for the next 25 years, shaving his head, wrestling barefoot. Being a Greek man pretending to be Turkish was not a stretch, said Andy; “That was his shtick, and that’s what he did. It wasn’t something that wouldn’t bother him”

One program even dug up the “then” and “now” photo, in a rare example of breaking kayfabe:

Ali Bey then and now

“Ali’s head is neatly shaven and he sports a handlebar moustache. His opponents sometimes take advantage of his moustache, however, by pulled it at both ends. Ali, obviously, takes exception to this,” noted a Stampede Wrestling program from Regina, Saskatchewan, adding, “One of Ali’s favorite diversions away from the wrestling ring is smoking cigars. And he presents a striking appearance walking about Regina avenues puffing on one of his stogies during his showings in the Queen City.”

Another story, undated, had the insightful headline: Ali Bey’s Mustache Secret to Success.

Twirling his pitch black moustache — which contrasts sharply his bald head, Ali Bey confessed with all outward signs of complete seriousness that a moustache to a Turk represents manliness and strength.

“If somebody should shave my moustache,” said Ali, “I would give up wrestling. Without it, I were to feel stripped of my power.”

Houston, Texas, referee Tommy Fooshee got to know Ali Bey. “He could make you laugh. He’d stand up in front of the hotel, looking at everybody. ‘What you looking at!?’ with his handlebar mustache. He was a great card player too,” said Fooshee.

The gimmick would include, at various times, manager Count Rossi, a harem girl named Princess Aida, a fez, a carpet. Promoting his arrival for Larry Kasaboski Northland Wrestling territory in northern Ontario, the hoopla noted “many in the audience will come especially to see Ali Bey, pot-bellied Turk. This little fellow stalks his opponent like a wild bull and can be just as dangerous.” And in a North Bay newspaper column, writer Britt Jessup, ballyhooed, “It is reported Hassen Bey, newest addition to Larry Kasaboski’s sideshow, will arrive by flying carpet late today for his bout with rough Rufus Jones tonight at the Gardens.”

* * *

It’s not the norm to see a wrestler in featured positions in New York City and Los Angeles within a short period of time.

Though Ali Bey never worked in Madison Square Garden, he’s all over the smaller shows in and around New York City, including the Jamaica Arena in Queens and Brooklyn’s Ridgewood Grove Arena, and over into New Jersey, like Trenton and Asbury Park.

But it was in Los Angeles where Ali Bey seemed to develop a following and where he befriended Hollywood stars. The “newcomer from Arabia” arrived in April 1951 and makes appearances around California until the end of 1953.

“My sister told me a story when she was like five years old and my other sister was seven. He knew Judy Garland, and Judy Garland used to come over and cook at the house with them. My dad used to teach her cooking, and they were cooking together and they were friends for years,” recalled Andy, referring to the star of The Wizard of Oz. “And my sister was saying, ‘We went to school, and used to say, “My dad knows Dorothy,”‘ and people were laughing. We’d get into fights. … ‘Stop lying. You’re making stories up.'”

Pat O’Brien and Ali Bey. Courtesy Stefanides family, photo by Thurston

There are photos of George Stefanides with Phil Harris (The Phil Harris-Alice Faye Show) and Pat O’Brien, who was affectionately called “Hollywood’s Irishman in Residence.” Andy said he was tight with Mickey Rooney, director Cecil B. DeMille, one of the original Tarzans, Elmer Lincoln, and even boxer Jack Dempsey, who refereed plenty of wrestling matches through the years. Early in his career, Stefanides befriended singer Cab Calloway, who attended and played at his daughter Sophia’s baptism in Montreal, and was the conduit to the Greek grappler becoming friends with baseball’s legendary “Splendid Splinter” Ted Williams.

There are also a couple of great letters in the family’s collection from fans that date from that time period. “My fellow workers and my entire family consider you the most outstanding and colorful wrestler who graced our city and state. We want to express our thanks for the many pleasant hours of enjoyment you provided for us through your outstanding skill,” wrote Frank Hoffer on July 8, 1951.

But a letter from some US Marines, dated July 23, 1952, that takes the cake. “We would like to know in advance when you wrestle so that we could come out and support you,” requested the “Alli Bai Fan Club” signed by more than a dozen Marines.

Letter to Ali Bey from the Marines

It’s a gem of a letter. Andy wishes he had more fan club information. He can remember his mother mailing out 8×10 signed photos to fans, but not a lot more.

* * *

Though the bright lights of Hollywood were one thing, the biggest run of Ali Bey’s career came in Texas — El Paso more specifically — and across the border in Mexico.

In 1950, when Andy Tremaine took over as the El Paso promoter, he created a World Light-heavyweight title for himself. It’s that title that Ali Bey wrested from the legendary Gory Guerrero — yes, the father to Chavo, Mando, Hector and Eddie — in 1963.

Stefanides had been in the territory in early 1953 — cut on the head by a fan with a can, late 1954, so had already gotten to know Guerrero, who took had taken over promoting in the city. He was back in 1958, headlining against Gory. It all set the stage for their 1963 battles.

On August 6, 1963, at the El Paso Coliseum, in front of 2,872 rabid fans, Ali Bey beat Gory Guerrero to win the title, taking two out of three falls over 42 minutes. During his title reign, Ali Bey turned around the likes of Omar Atlas and Juan Garcia, until dropping the title back on September 24, 1963, on a truly stacked card:

(Coliseum, att.-5,510) … (World Heavyweight Title) Lou Thesz (c) drew Rito Romero (both co) … Referee: Mike Burnell … (World Light-Heavyweight Title) Gory Guerrero beat Ali Bey (won title) … (Ladies World Title) June Byers (c) beat Millie Stafford … (International City Tag Team Title) Juan Garcia and Mad Mongol (c) beat Nikita Mulkovich and Joe Turco … Paul Harrison beat Omar Atlas

To add to the pain of losing the title, on October 1 of the same year, Mad Mongol beat Ali Bey in two of three falls in a “Battle of the Claw Holds” match, meaning the Turk lost the right to use the claw hold in El Paso.

Gory Guerrero and Ali Bey took their act on the road too, including into New Mexico.

Naturally, father had shared plenty of stories about Texas with his son.

The young Guerreros would be part of the promotional team, driving around town promoting the matches, giving out some free tickets to the matches. If Ali Bey was in the car, it reeked.

You see, Stefanides loved garlic. “The old man would eat raw garlic, one after another, like peanuts,” laughed Andy.

The idea was that it was healthy, and Stefanides was an early proponent of proper eating. “He lived off the Earth. He was always eating fresh fish, vegetables,” said Andy.

A young Gino Brito was one of those unfortunate few who drove Ali Bey around, in this case, in the Detroit territory. “I hated that he used to eat so much garlic in the car. People knew, ‘Oh, you took Ali Bey in your car? It smells like garlic all over the place,'” Brito chuckled. “It would take two, three days before the smell went away.”

When the wrestlers were settled in a hotel or an apartment, rather than a quick baloney blowout as they went town to town, it would be Stefanides doing the cooking, like fresh pasta with olive oil and a boiled egg. “My dad was the cook for all those guys. He used to do the cooking, because as I said he traveled around the world, so he learned to cook,” said Andy.

As for Mexico, there are some fabulous posters with Ali Bey on them, though the records themselves are even tougher to figure out than which Ali Bey was which.

* * *

There were plenty of other of highs and lows throughout the long career of Ali Bey … who would return to being George Kanelis when he worked in Ontario for Frank Tunney, circa 1955, and then again in 1965 in Toronto and Montreal. For that ’65 stint, one newspaper hyped “The Great Greek”: “Kanelis, once a regular feature on North American cards, is becoming well known in his latest comeback attempt and is expected to present a fine show.” Kanelis was often seen laying down for bigger stars on Maple Leaf Wrestling, taped at the CHCH studios in Hamilton.

The in-ring death of 31-year-old Dennis Clary (Vincent Lizdenis) during a bout on January 30, 1955, in Tuscon, Arizona, was something that haunted Stefanides. Clary had been having some health issues, but had been cleared to wrestle Ali Bey at Tuscon’s Sports Center. Instead, he collapsed during the match; a tumor at the base of his brain caused his death. Clary and Stefanides had worked together plenty before the match, though the California bodybuilder Clary only started wrestling in 1949. As upsetting as it was, what was worse was that Arizona promoter Mike London wanted to advertise Ali Bey as a killer, and Stefanides wanted none of that, and didn’t work the territory for years and years.

Stefanides himself never suffered any major, major injuries. On a New Year’s Day show in El Paso in 1953, he was cut in the head by a post-match can thrown by a fan, and required medical attention. Maybe he learned? In October 1959, he ducked chairs hurled by fans in Detroit that hurt two police officers.

In North Carolina, working for Jim Crockett Sr., Stefanides found plenty of work, competing from late 1951 to early 1952, then returning for the fall of 1956, and staying the next two years, even as he made his way lower down the cards.

There weren’t a ton of title belts around the waist of the “5×5” Ali Bey, but one was the Rocky Mountain tag team titles with Danny “Bulldog” Pletches in February 1953 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. When he arrived in the state, he’d been hyped as “claimant to the Turkey national heavyweight crown.”

* * *

By the late 1960s, the active wrestling portion of Ali Bey’s career was winding down, and he and his family settled in Toronto, where George Kanelis was an oft-used referee for promoter Frank Tunney — his hair having grown back. Related, Stefanides found work as a security guard at Woodbine racetrack with other Toronto veterans (and referees) Pat Flanagan and Tiger Tasker. Stefanides worked there until he turned 75.

“When he got out of the business, he got out of the business and he was retired from the business,” said Andy. He might call Chris or John Tolos on occasion, or drive to Niagara Falls, Ontario, to visit with Tony Parisi at his Big Anthony’s restaurant. Wrestler turned painter George Gordienko would call, and the proof of the friendship is that the Stefanides family have a number of Gordienko originals.

Which made it a surprise when, in the late 1980s, wrestling was on TV, and father turned to son and said, “Let’s go to the matches.”

Ever dutiful, Andy, who worked in sales for 30 years, took his father to a WWF show in Hamilton on July 13, 1986, at Copps Coliseum. As he was at the ticket window, one of the WWF agents, Rene Goulet, recognized Stefanides. Goulet started crying and said, “I thought you were dead. We didn’t know where you were.” Instead of buying regular tickets, the Stefanides duo sat backstage.

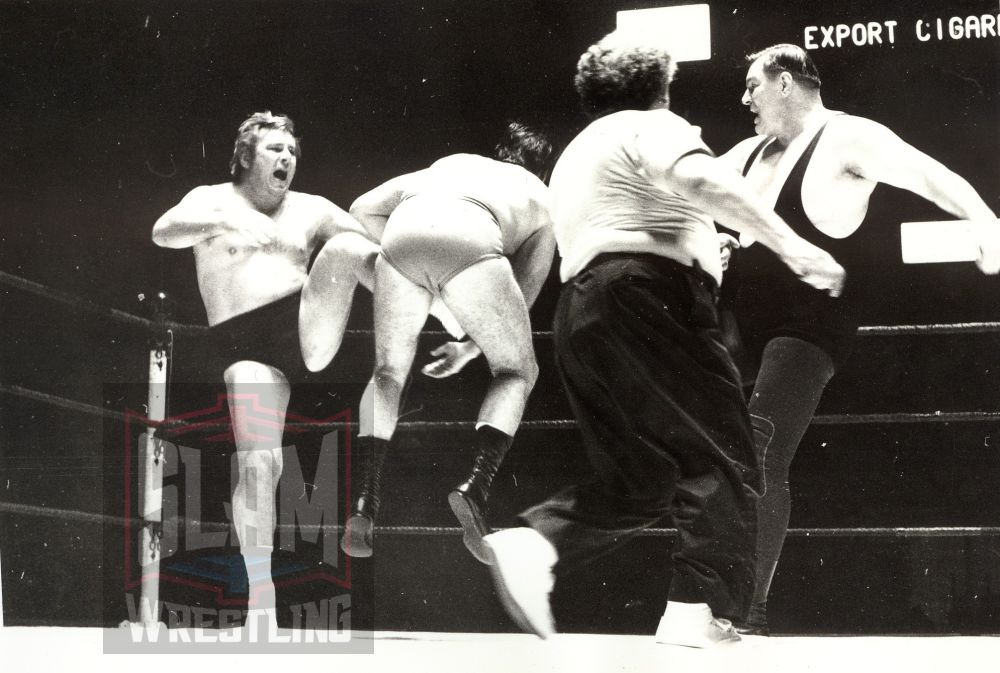

Ali Bey in a tag bout against Fred Blassie in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on March 6, 1953.

Fred Blassie was there and Stefanides started dropping names from the past that they’d both know. Blassie was floored. “Who the hell are you? How do you know these names?” Stefanides revealed himself — and more. “They get up and they start doing their thing,” said Andy. “He says, ‘I’ve still got, I’ve still got it. I’ll still knock the shit out of you,’ and Blassie’s laughing.”

Stefanides was also able to remind Randy Savage — who was with Miss Elizabeth — that he used to change his diapers, back when he was on the road with Angelo Poffo. Savage vowed to call his father later that night.

While Stefanides wasn’t a regular at the shows after that, it lit a fire for Andy, who wanted to know more about his father’s career.

In 1955, George Kanelis heads to the ring with Sweet Daddy Siki in London, Ontario. Terry Dart collection

They went together to see Sweet Daddy Siki at a Toronto bar where he hosted karaoke. Andy went up to Siki and, pointing to his father, said, “The old man there says he knows you.” Siki promised to come by later, and, when he did, he started crying. “The old man’s like, ‘Get off me, stop crying ya baby,'” said Andy. It turns out that Siki was just a young pup in Los Angeles, and Stefanides had been kind to him, inviting him to Muscle Beach, showing him a few moves.

Andy had the idea to take his father to a Cauliflower Alley Club meeting in Los Angeles, before it had been opened to the fans. As an industry-only event, including boxers and actors, it was a unique club. What Andy didn’t know was that his father had been a Day 1 member, as wrestler/actor Mike Mazurki had been a close friend in Los Angeles and had signed up Stefanides as a Lifetime Member.

It remains a fond memory for Andy, as his father died in 2001.

Since then, he has spread the gospel of Ali Bey at other wrestling events, like the Cauliflower Alley Club, the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame when it was in upstate New York, and the Titans in Toronto dinners.

* * *

Georgios and Diamante Stefanides.

Georgios and Diamante were married 56 years, and he died two years after she did. “They were a very happy couple, with lots of grandchildren,” said Andy. For Diamond, it was complications from diabetes that ended her life, on January 26, 1999.

Andy moved back from the US and took care of his father for two years. His memory was an issue. “He couldn’t remember what he had in the morning to eat, but he could tell you where he was in 1940, at this street, and who he was with, that’s how good his memory was,” said his son.

The old wrestler fell, broke his femur. The surgeon at Etobicoke General Hospital was stunned at his physical shape, amazed that an 89-year-old man could have the muscle tone of a 25-year-old. Three days after the surgery, his kidneys weren’t working right, which complicated things, and the next morning, December 4, 2001, he had a heart attack in the morning, and a fatal one that evening.

* * *

It’s a complicated career to sum up, admits Andy Stefanides. Ali Bey was on top of the card here, but not there; he gave up the gimmick every so often to work near his Toronto home. The wrestlers he has talked to at various reunions always had lots of great things to remember about his father — once they realized which Ali Bey they were talking about.

ALI BEY PHOTO GALLERY

[modula id=”153733″]