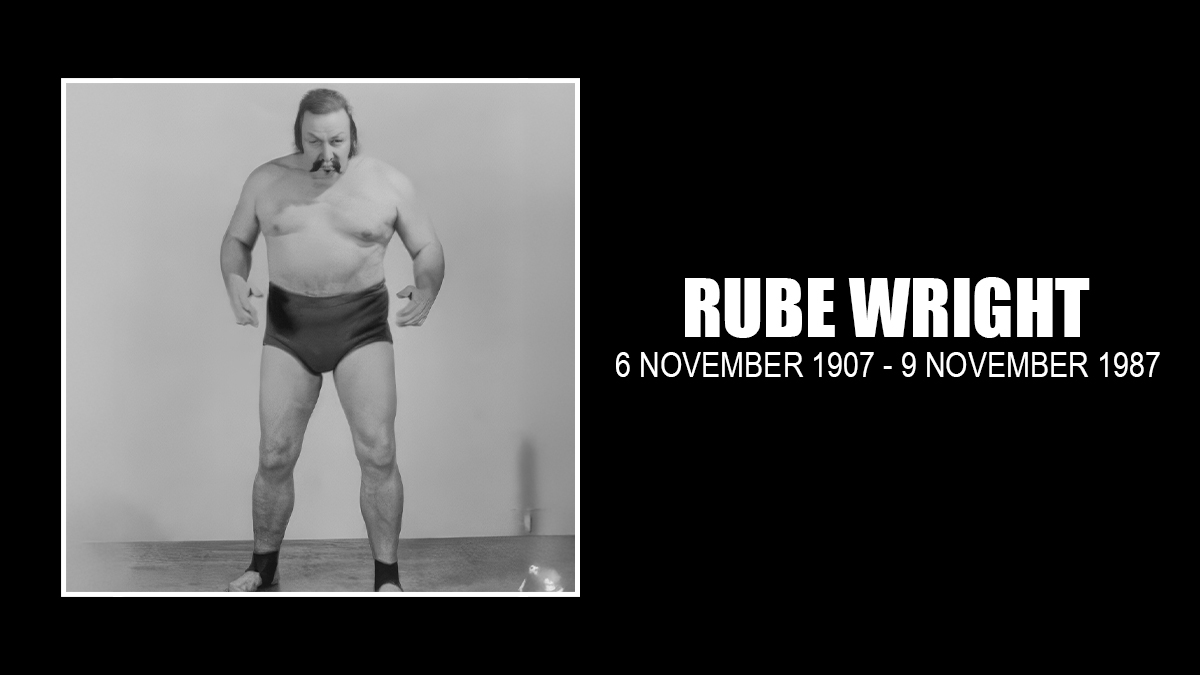

For a few months in 1942, “The Preacher’s Son” Rube Wright had as strong a claim to the world heavyweight championship as any of his pro wrestling contemporaries. Wright was born in Texas in 1907. He was one of 11 siblings born to James King Wright, described as a “rough-house bronco-buster” and farmer. At some point in his life, the elder Wright turned to the Lord and became a Holiness preacher and moved his family to various locations around Arizona. Rube followed one of his older brothers who had gone to Pasadena, California, to attend Bible school. Wright found his way to Hollywood, worked in a pie shop, and started wrestling in the amateur clubs.

Wright won the 1932 Southern Pacific AAU “over 191 lbs.” championship and hoped to try out for the Olympic team. Unable to raise the funds to travel east for the try-outs, he turned pro instead. He gained a reputation as a tough mat man in the smaller venues and was considered the “club champion” of Southern California. Wright toured around the US and Europe through the 1930s. He recruited a younger brother Big Jim Wright to join him on the pro circuit. Jim initially used the name Kolo Stasiak. In the summer of 1936, Wright traveled with Danno O’Mahoney to Ireland where they had a big match in Dublin with the Wigan catch-as-catch-can legend Billy Riley serving as the referee.

The Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles was one of the main pro wrestling venues on the west coast and in 1940 was under the control of Jack Daro. Daro’s older brother “Carnation Lou” had “retired” when the California State Athletic Commission (CSAC) had placed him under investigation. Toots Mondt and his brother Art were involved with the Daros’ operation in an “unofficial” capacity as well.

The Daros and the Mondts launched a “world heavyweight championship tournament” and invited all title claimants and contenders to participate. Jimmy Londos, who claimed to be “the undisputed world heavyweight champ” declined to take part, but offered to meet the winner of the tourney. Competitors included Rube Wright, Vincent Lopez, Dean Detton, and Woody Strode. The Daro/Mondt tournament went on for 32 weeks and ended on May 15, 1940, with Lee Wykoff defeating George “KO” Koverly in the final. The Daros were nearly bankrupt and many of the mat men had not yet been paid. Wright, Lopez, and Hardy Kruskamp formed the American Wrestler’s Association and tried to recoup their back pay. Boston-based promoter Paul Bowser entered the fray and filed suit against the beleaguered Olympic Auditorium, citing that he had been owed a share of the earnings as well.

The CSAC pulled the promoter’s license of Jack Daro. The Mondt boys, never officially licensed in the first place, were left out in the cold, at least for the moment. Wrestlers George Zaharias and Nick Lutze were granted licenses as promoter and booker, respectively. Zaharias’ run didn’t last long and veteran promoter Ray Fabiani moved in, keeping Lutze and bringing Toots Mondt back into the picture. The Olympic’s top three stars at the time were Sandor Szabo, Rube Wright, and Pat Kelley. Wright’s persistent challenge to Londos was heavily ballyhooed, and the Golden Greek reportedly left the Golden State rather than face him in the ring.

In April of 1942, the CSAC dethroned Londos, removing their recognition of him as the world heavyweight wrestling champion. Fabiani was quickly on the scene to announce a tourney to replace him and crown a new king. Tournament matches were held on the weekly Olympic cards and a veritable who’s who of the current mat stars took part, including Danno O’Mahney, Ali Baba, Vincent Lopez, Iron Mike Mazurki, Jumping Joe Savoldi and the old war-horse Ed “Strangler” Lewis, in addition to Fabiani’s “big three” Szabo, Wright and Kelley. Latter reports noted that, “Londos had refused to meet Rube Wright, who was king of the outlying clubs, and had been chasing ‘Jeemy’ all over the place demanding a showdown.” (Los Angeles Daily News, 8/19/42) Another sportswriter commented, “Wright is really responsible for the tourney, as he was the man who forced Londos’ hand and caused him to run…” (Los Angeles Times, 8/19/42)

A couple months into the tourney, San Francisco promoter Joe Malcewicz entered his top man “Powerhouse” Frank Sexton. This was followed by the irrepressible Jack Pfefer who showed up with the Swedish Angel (Phil Olafsson) and Karol Krauser and declared that they would “force their way into the tourney.”

The Swedish Angel was given a “test match” with Strangler Lewis. The grand old man of the mat agreed to attempt to throw the Angel twice within 30 minutes. They met on July 1, at the Olympic. Lewis tossed his challenger in 11:07, but was thrown himself a little less than eight minutes later. They pushed, pulled, and tugged for the remaining time with no additional falls being registered. It was noted that Fabiani, Mondt, Lutze, all the wrestlers in the house, and a state athletic commissioner all sat glued at ringside watching the contest. The Angel and Krauser were both admitted into the tournament.

Sexton was shaping up as the favorite to win the tourney. Wright returned to the tourney for the first time since late May on July 22 and knocked Kelley out of the competition. The following week Wright defeated Szabo, Sexton beat Zaharias, and Lewis won over Krauser. Zaharias and Krauser were eliminated. Karl Pojello with the French Angel (Maurice Tillet) in tow, arrived on the scene and threatened to chase the Swede version of the “angel” gimmick out of L.A. It was too late for the French Angel to enter the tourney but Fabiani booked him for some non-tournament matches. Pojello’s Angel debuted on August , and defeated Kolo Stasiak (Jim Wright). On the same card, in a tournament contest, Szabo beat Wright with a leg-strangle. The loss didn’t put Wright out of the competition, as the rules stated that a wrestler remined in the running until he had lost two matches to a seeded opponent.

They were re-matched on the next card, and this time Wright proved the victor, vanquishing Szabo with his pet maneuver, the step-over toe hold. The tournament was down to three finalists — Wright, Sexton and the Swedish Angel. Wright and Sexton were scheduled to square off on August 19, the 19th week of Fabiani’s tournament. Sexton ducked out without any notice or explanation. Did Sexton fear that Wright would “shoot” on him? Fabiani, apparently perplexed, was ready to cancel the whole shebang. Mondt and Lutze convinced Fabiani to bring it to a conclusion and to go ahead and pit Wright and Pfefer’s Angel as the final bout with the winner to be proclaimed the world heavyweight champ. Wright was certainly not Fabiani’s top choice to be the champ. He was considered a “troublemaker” since his rebellion against the Daro brothers a few years earlier. Plus, Rube had a reputation as a tough “shooter” with an independent streak.

Wright and the Swedish Angel met for the title and belt on August 19 with no less a personage than Bull Montana handling the referee chores. There were 9,500 fans were on hand to witness the crowning of a new mat king. A total of 51 wrestlers had participated in the tournament and it was now down to the last two men standing. It proved to be a rough, grueling battle. At the 41:30 mark, Pfefer threw in the towel as his man writhed in agony from Wright’s step-over toe hold. Olafsson suffered an injury and was unable to continue. He forfeited the second fall and thus the match to Wright.

An in-ring ceremony was held and CSAC commissioner Everett Sanders presented Wright with the trophy diamond belt and he was announced as the new world heavyweight wrestling champion. Wright shared that designation with four compatriots: Wild Bill Longson (National Wrestling Association), Roy Dunn (National Wrestling Alliance-Kansas), Steve “Crusher” Casey (American Wrestling Association-Boston), and Orville Brown (Mid-West Wrestling Association).

Wright defended his title around Southern California briefly, but plans were underway by the “powers that be” to weed him out and bring Londos back. His “world tile” was reduced to a “California state title.” Determined to make hay while the sun was shining, Wright accompanied Pfefer’s merry band when they returned east. Under Pfefer, Wright made appearances from Washington DC for Joe Turner up into New England, billed as the world champ. Londos was back in southern Cali by November of 1942, and, as if he never left, enjoyed the billing of “world heavyweight champion.”

In 1943 Wright returned to Los Angeles content to accept his role as the state titleholder. Sexton also re-appeared and was ballyhooed as “the uncrowned wrestling champion of the world.” A series of matches between the two bruisers was held, resulting in Sexton taking the state crown.

At the 2010 Cauliflower Alley Club reunion, veteran wrestler Ted Tourtas, then in his eighties, recalled Rube Wright for a collection of historians:

Rube was a good friend. Another tough wrestler. Rube was 275 pounds, he had wrists about this wide, his ankles were about that wide, you couldn’t get an ankle hold or a wrist hold to beat him. Huge guy and he was a very tough wrestler. When I met him, I never even dreamt I could beat him; I just wanted to look at him. And we became pretty good friends. He was a lifeguard in Santa Monica. We used to go to go abalone hunting. They don’t have abalones too much more in this part of the country. They’re a shellfish on the rocks. You’ve got to dive by, get a crowbar and pull them up. They’re pretty good. Well, I went with him a couple of time. I wasn’t too much of a diver or a swimmer. We’d go out in the rowboat and I tried to dive a couple of times and I did this [simulates drowning]. “You go down for abalones and I’ll scrape them off the rocks.” So I’d sit in the boat and he’d bring them up to me in a gunnysack. Rube stayed down there like a fish. Rube loved to have them for breakfast.

There was a guy called Johnny Goldsmith. He was a one-eyed guy. He lost an eye in the war. And Johnny would have made a light-heavyweight champion, but when he lost the eye he had some problems getting his boxing license. Anyway, those were two of the guys who used to go abalone fishing. All of a sudden, we see something and we turn around and Johnny says, “Geez, Rube is probably wrestling with that shark.” There was a shark down there, pretty good size. All of a sudden we saw that fin going swish. He beat the shark in a shooting match!

The Teamsters Union when they were fighting in California before they killed Hoffa and all that, they hired him as a bodyguard for the West Coast. San Francisco, I forget his name. The leader of the Teamsters hired Rube as a bodyguard. So, there was a pier there and Rube happened to be by the pier when somebody’s hit men were gonna hurt him. So he wasn’t going to fight all of them. He just pulled the telephone and all off the wall and started throwing it at them and then he dove in the water because there were hit men there. That’s how tough Rube was.

Wright kept active on that mat and in 1952 he re-emerged as the Manchurian seafarer Lu Kim, “the Sinbad the Sailor of the mat.” He offered $1,000 to anyone who could pin him. A publicity release stated that Kim “combines jiu jitsu tactics with the American catch-as-catch-can style. Furthermore, unlike most foreign heavyweights he wrestles ‘cleanly’ in his exhibitions.” He kept up the Lu Kim gimmick for the rest of his career, into the mid-1960s.

Bob Orton Sr., who toured Japan with Wright in 1960, spoke very highly of him as both a tough and skilled mat man. Stu Hart told historian Don Luce that in his opinion Wright “would have taken Lou Thesz in a shooting match.” Karl Gotch stated that Rube “was one tough SOB.”

Wright retired to San Francisco, where he was an avid scuba diver and abalone hunter. He sometimes found work as an underwater welder. He died on November 8, 1983.