It was 3 a.m., and I couldn’t get to sleep. The Killer Elite (1975) was on some basic cable movie channel. It had been on for a while already but it was just getting to the good part where James Caan battles a gang of ninjas at the Suisun Bay Ghost Fleet, a graveyard of World War II era warships rusting away in a sleepy pocket of the San Francisco Bay. The Killer Elite was a Sam Peckinpah film, so swords and bullets soon flew from all angles in dramatic slow motion. In the melee, a curiously red-headed ninja got drilled by a submachine gun with blood-packed squibs exploding across his chest as he sunk to his drawn-out death.

It was just another late night action flick but a wave of sadness came over me because I knew that ninja.

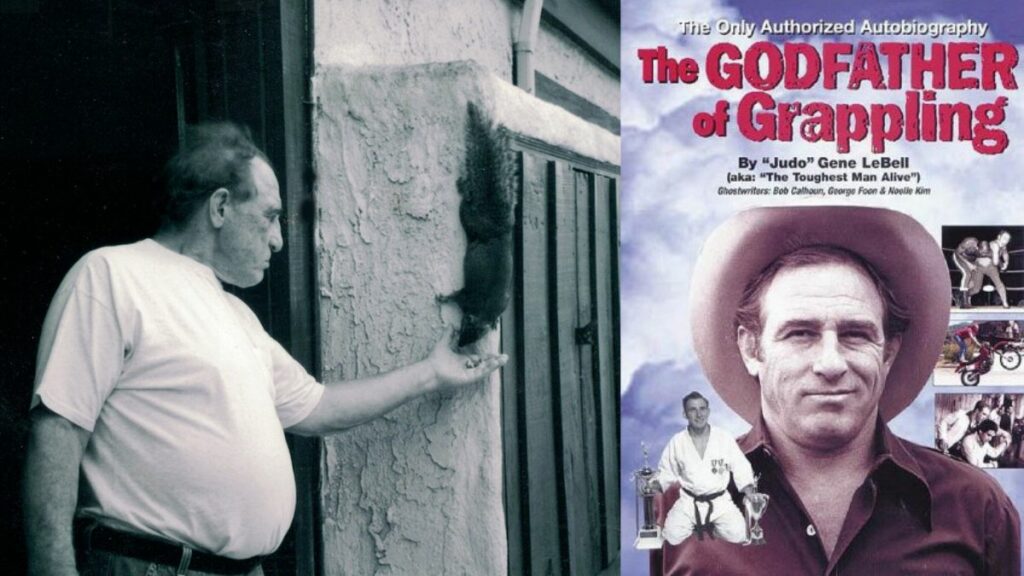

He was “Judo” Gene LeBell, and he had been like a grandfather to me since I collaborated with him on his autobiography, The Godfather of Grappling in 2003.

With his long career as a stuntman going from the late 1950s through 2010, this was hardly the first time he’d bought it onscreen, but most of us will never see our grandads get gunned down in a Sam Peckinpah movie. As silly as it sounds, I called him the next day to check on up on him.

“How’s it goin’ champ?” he said when he answered. He was fine for a few more years yet.

I just found out through a friend’s Facebook post that Gene LeBell died on August 9, 2022. I don’t have details but he was 89, so I doubt it was in a shootout with ninjas on a battleship, although anything is possible with the life he led. Gene was an ass-kicking renaissance man who had lived enough macho for 100 regular Hollywood tough guys. He was a two-time national judo champion, who became a pro wrestler because that’s where the money was and then added crashing cars and setting himself on fire as a Hollywood stuntman to his repertoire for good measure.

He managed to maintain all three careers simultaneously, adding one dangerous enterprise to another in a house of cards that only he could keep from collapsing. He’d wrestle John Tolos at the Olympic Auditorium on Saturday, got thrown off a cliff by a horse while doubling James Whitmore in a Big Valley episode on Monday, and taught judo at his dojo near Paramount Studios in between gigs. In fact, he still taught leg locks and sleeper holds at his protégé Gokor Chivichyan’s Hayastan MMA Academy in North Hollywood almost till the end. Bruce Lee, Chuck Norris, Bob Wall, Roddy Piper, Ronda Rousey and several decades’ worth of aspiring stuntmen, pro wrestlers and mixed-martial-artists were among his students.

James Caan chokes Gene LeBell.

But even the most detailed litany can only scratch the surface of this man’s legacy. He was in hundreds of films and TV shows, and that’s not counting all of his appearances inside the ring and out while broadcasting wrestling from the Olympic. He gets chucked in the pool by Steve Martin in The Jerk (1979). He’s the cabbie that pulls a pistol on Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker in Rush Hour (1998). He got tossed around by Elvis Presley during a bar fight in Paradise, Hawaiian Style (1966), and body slammed repeatedly by Mike Mazurki in 4 for Texas (1963) with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. And he’s in just about every one of the original Planet of the Apes movies.

“What was that like?” I asked while we worked on his book, hoping to get some great anecdote about Charlton Heston.

“It was just a bunch of stuntmen in monkey suits riding around on horses,” he said, and that was it. End of story. Stuntmen in monkey suits.

After taping several of our long conversations, I quickly found that what were fondly-held cult movie memories to a doughy nerd like me, were just residuals to Gene, won from another call to the Sony or Universal backlots. He didn’t give me a whole lot on being directed by Scorsese in Raging Bull, but he regaled me with tales from the set of The Fall Guy, a 1980s action show with Lee Majors as a stuntman who moonlights as a bounty hunter. Gene loved The Fall Guy because he and all the other stunt guys got to realize every crazy car crash and motorcycle gag they ever dreamed up of over the course of its 112 episodes. And its kitschy theme song about being “the unknown stuntman who made Eastwood look so fine” was like Dylan to the people who had lived that life.

If you watch enough TCM or MeTV, you’re going to see Gene tussle with James Garner or Jim Brown sooner or later. “I made a lot more money from losing fights than I ever got from winning them,” he told me more than once, though he did win more than a few. He choked out top-ranked light heavyweight boxer Milo Savage in what many consider the first mixed-marital-arts fight back in 1963. Before that, he bested legendary judoka Johnny Osako in the National AAU Judo Championships in San Francisco in 1953, and won another national title in Los Angeles in 1954. Did I say he wrestled a bear? Yeah, he wrestled a bear.

Did the bear tap out?

And then there are the Hollywood urban legends: Gene choked Steven Seagal unconscious back in the 1990s, or he was the real “Cliff Booth” who put Bruce Lee in his place on the set of The Green Hornet in the 1960s. There’s more than a bit of truth to both rumors, but they were the things Gene least wanted to talk about, even though they were the stories that would have sold the most books for us. “That’s braggadocios,” he’d say when I’d bring them up. When I asked him if he did choke out Seagal, he raised his eyebrows and looked at me like I was the dumbest man he’d ever met. End of story.

And there again, the curriculum vitae gets in the way of the man’s life. Who he was gets obscured by NWA championship matches in Amarillo or car chases in old Starsky and Hutch episodes. To write about Gene is to feel like you’re perpetually burying the lede and don’t know where to start. Writing about his mother, Aileen Eaton, the boxing and wrestling promoter in Los Angeles from the 1940s to her retirement in 1980, sends me off tangents I can’t easily return from. There’s seven-year-old Gene learning how to grapple from Ed “Strangler” Lewis while his mother balanced the wrestling promotion’s books, or Gene at the same age seeing his father die from a swimming accident during a beach trip. Is there a way to cram in Gene’s friendship with George Reeves, TV’s first Superman who died from a gunshot to the head in a Hollywood mystery in 1959? There probably isn’t, but I really should.

Gene’s life is a Zen garden, even though he eschewed martial arts’ more spiritual side. “Don’t call me sensei, sifu or shihan,” he often told his students. “Just call me Gene.”

Gene loved grappling more than anything, except for maybe motorcycles. I had to do something to gain his confidence when I was working on his book, so grappling it was. I sure as hell wasn’t going to get on a motorcycle around him after hearing so many stories of him, Gary Busey and several stuntmen all trying to kick each other off of their bikes while riding through the hills overlooking Big Bear Lake. But going to Gokor’s dojo for Gene’s Monday night submission holds seminars wasn’t going to be pain free either. Every time I went there, Gene attempted to demonstrate these excruciatingly painful bone-breaking finger locks on me.

“Gene, I need my fingers to type your manuscript,” I pleaded. Gene could see I had a point so he showed me some knee locks instead. I walked around with what he called a “Transylvania twitch” for a while after that, but hey, I could still type.

The first time I visited Gene’s townhouse in Sherman Oaks, he ushered me into a parking spot on the street and had me come around to the side of the house with him to his garage, which was crowded with a red Cadillac, an oversized Honda motorcycle, stacks of grappling books, and several jars filled with assorted nuts. Gene poured some shelled walnuts into the palm of his hand and walked into his driveway. Pigeons descended from the palm tree adjacent to his property and a squirrel scurried up his leg to get the nuts from his hand. He had names for all of them. There was Nibbler and Mrs. Nibbler (the squirrels) and Spot the pigeon, and many more.

Gene LeBell with either Nibbler or Mrs. Nibbler.

“I really want to get Spot and Nibbler to both eat out of my hand at the same time,” he told me. “I’ve almost gotten them to do it, but something always breaks the deal.”

And that’s how I want to remember Gene. He was the toughest man alive and a self-described sadistic bastard who wanted nothing more than than to bring the pigeons and the squirrels together.

Ivan Gene LeBell was born in Los Angeles on October 9, 1932, and he died there on August 9, 2022. He is survived by his wife Midge, his daughter Monica, and son David.

RELATED LINKS

- Buy The Godfather of Grappling at Amazon.com or Amazon.ca

- Oct. 11, 2022: Friends, disciples say goodbye to Judo Gene LeBell

- Aug. 10, 2022: Mat Matters: Gene LeBell, dead at 89, was an old softie

- Aug. 10, 2022: Wrestling, MMA, movie worlds pay tribute to Judo Gene LeBell

- Aug. 11, 2022: Guest column: Gene LeBell was one of a kind

- Nov. 24, 2009: Los Angeles promoter Mike Lebell dies

- Oct. 19, 2006: Straight shooting with ‘Judo’ Gene LeBell

- www.genelebell.com

- Guest Column story archive