Almost two decades after he retired, Stan Hansen continues to be a true legend in the wrestling business. Not only is he widely considered the greatest gaijin wrestler in Japanese puroresu history, but he has also been inducted and honored several times by different organizations.

He is a member of the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame, the WWE Hall of Fame, the Texas Wrestling Hall of Fame, and The Wrestling Observer Hall of Fame, among others. The George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame is next.

Stan Hansen and Barbara Goodish, widow of Bruiser Brody, at the 2016 George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame induction weekend. Photo by Greg Oliver

During induction weekend July 20th-22nd, at the National Wrestling Hall of Fame Dan Gable Museum in Waterloo, Iowa, Hansen will be honoured with the Frank Gotch Award, a prestigious recognition reserved for those wrestlers that, “through their athleticism and toughness in the ring, brought a higher level of respect to professional wrestling from both inside and outside the business.”

Honourees into the Tragos/Thesz Hall of Fame this year are “Mr. Wonderful” Paul Orndorff and “The American Dream” Dusty Rhodes, and Magnum T.A. is receiving the Lou Thesz World Heavyweight Championship Award.

Hansen was asked about his latest honour, and after some though, considered that “being honored makes me feel better about this whole thing [his wrestling career].” He mentioned how he got to work with some of the finest amateur wrestlers in his day, stating that, “although I’m not an amateur wrestler myself, I got to work with many of the best amateurs of my day. I’m glad that people think my wrestling style had a positive impact.”

This honor fits Stan Hansen perfectly. He is a wrestler that, over the decades, brought legitimacy to a sport that was long derided as phony, cartoony, and low-class. Though he started his wrestling career in the United States, he spent the majority of it in Japan, working for the two biggest promotions of the 1980s and 1990s, New Japan Pro Wrestling and All Japan Pro Wrestling.

Stan Hansen never took his reputation seriously as a wrestler. In his mind, wrestling was his job, and his bosses asked him to put his best effort into his wrestling. That was it. Hansen was only serious when it was in the ring, and took his competition as seriously as possible. He didn’t care much about his reputation as much as so many people do today.

With the Frank Gotch Award in his near future, Hansen spoke about his time in Japan, what he thinks of himself, and some of his fondest memories of his wrestling career across the Pacific Ocean.

Like many of wrestling’s most notorious tough guys Hansen’s first exposure to pro sports was in football, though he didn’t stick. That sport helped him develop proper conditioning and endurance, which became critical to his incredible wrestling style. In fact, Hansen’s style in Japan was so intense that his former partner Ted DiBiase said that Hansen was ‘on go’ all the time.

“One had to be in the best shape possible if they hoped to go toe-to-toe with Hansen,” said DiBiase, who, like Hansen had a substantial run in Japan, and was presented with the Frank Gotch Award in 2007. (Other honourees in the past are Tom Drake, Dan Severn, Jesse Ventura, George Scott, Gene LeBell, Nikita Koloff, Ted DiBiase (2007), Penny Banner, Mick Foley, Jim Duggan, Joe Laurinaitis, Jim Brunzell, Diamond Dallas Page, Beth Phoenix, and Lex Luger.)

Hansen said football that helped him considerably, as the endurance that he developed allowed him to work out to such an extensive degree that it made even the notorious workhorses of Japan turn their heads. Hansen described several times when he was in the gym working out and pushing his endurance even further at 6 a.m., while the other wrestlers still slept.

This incredible endurance became a theme in Hansen’s bouts in Japan. If one were to watch his matches, the thing that would stand out most would be how much energy Hansen has, even as the match wears on and both he and his opponent beat each other savagely.

But it wasn’t out of malice or hatred that Hansen hit so hard. He was notorious for having poor eyesight in the ring, and he took the concept of “strong style” very much to heart. Even today, long after the deepest of secrets about pro wrestling have been exposed in North America, wrestling is treated more or less as a sport, a legitimate athletic contest in Japan. As such, the in-ring action and athleticism was always seen as paramount in Japan, which is why one rarely saw any cartoon character or outlandish gimmicks in Japanese wrestling promotions.

Stan Hansen was living proof of this. His toughness in the ring could not be overstated. This was a man who could take an incredible amount of punishment in the ring and dish it out with just as much force. To this day, Hansen’s Western Lariat is considered one of the stiffest and most vicious versions of the move. It has also been emulated by many wrestlers over the years, from Hansen’s erstwhile opponent Kenta Kobashi, to fellow Texan John “Bradshaw” Layfield.

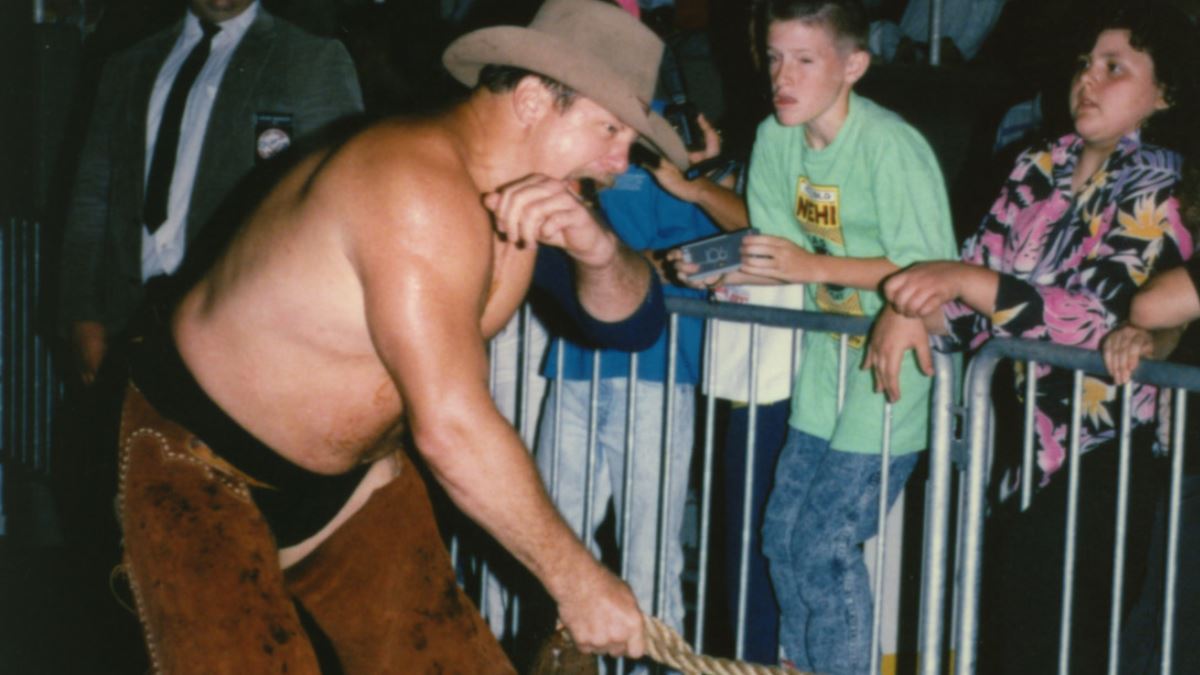

A rope-swinging Stan Hansen during his WCW days. Photo by Terry Dart

But this toughness and endurance were facets of an underlying philosophy that Stan Hansen followed all the time. “I tried my hardest in the biggest shows in front of 40,000 people, or in the smaller venues with 250 people. It didn’t matter to me; I worked as hard as I could to give the fans a good match,” he said. Hansen was of the mind that the fans deserved to see a good match, and he was determined to put one on for them. He made his opponents fight hard in the ring to match his stamina, even if they didn’t want to.

“The Lariat” never expected his career to take off in the way it did. “I gave myself three years for wrestling, and if it didn’t work out, I’d go back to teaching and coaching,” he said. But instead of doing that, Hansen became a multi-time World Champion in All Japan Pro Wrestling, a certified legend in Japan, and one of the most revered wrestlers alive today. Even the lariat, a basic clothesline wrestling move that’s seen virtually everywhere, is more synonymous with Hansen than anyone else.

“Thankfully,” he said, “things worked out, and I got one opportunity after another.”

While his in-ring career ended in 2001, Hansen’s legacy in pro wrestling still lives on. His book, The Last Outlaw, was published in 2012, and he makes occasional appearances here and there for wrestling conventions and special ceremonies.

When asked about how he feels about all of these awards and recognitions, Hansen chuckled.

“I cannot even begin to stop and look at this organization or that organization. To be recognized by anyone is an honour. I’m pleasantly surprised for being recognized in this respect, and am really honored,” he said humbly.

It is not hard to see why people still praise and honour him even now at age 67; through his own iron will and nearly-unmatched toughness, Stan “The Lariat” Hansen brought a level of respect and admiration to the professional wrestling industry. Given all that he has done, it seems only fitting to honor him with a distinction named after a man, Frank Gotch, who was to wrestling what John L. Sullivan was to boxing. After all, Hansen dominated the wrestling world in a country where it was treated as a pure athletic contest.

TRAGOS/THESZ CLASS OF 2017 STORIES

- July 23, 2017: Tragos/Thesz HOF induction ends on a Wonderful note

- July 22, 2017: Tragos/Thesz Hall of Fame: Chuck Taylor wins inaugural HOF Classic tournament

- July 17, 2017: ‘Athleticism and toughness’ defined Stan Hansen

- Apr. 7, 2017: Rhodes, Orndorff top 2017 Tragos/Thesz HOF class

RELATED LINKS