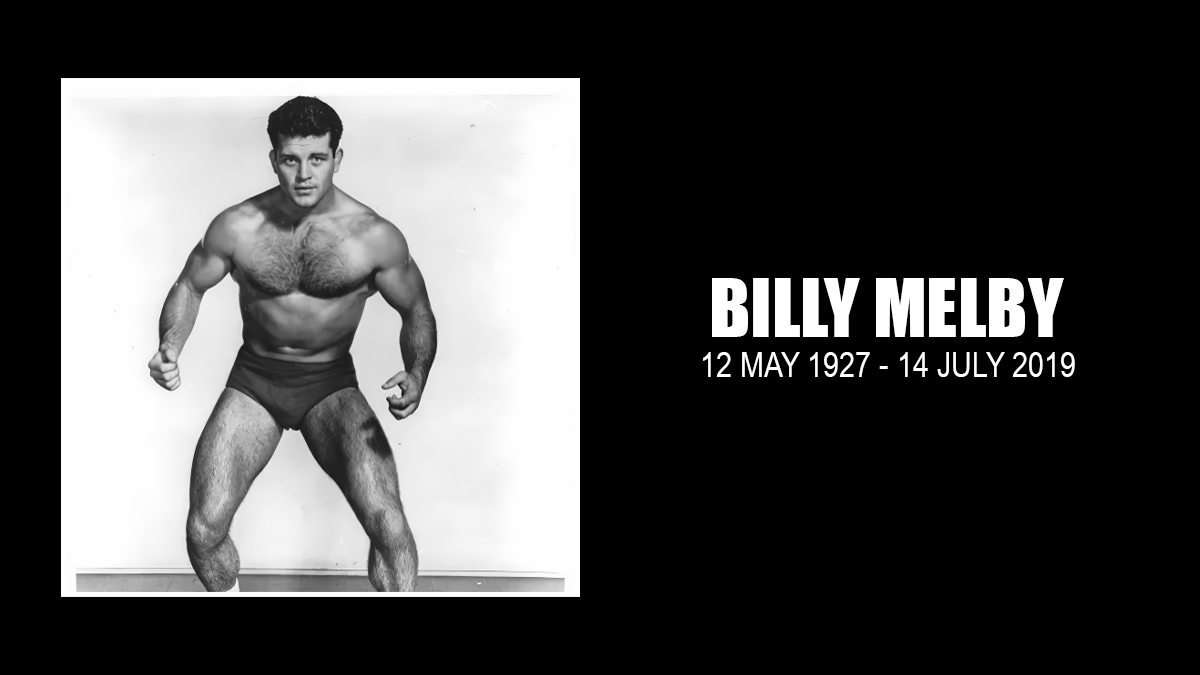

Bill Melby had one of the most memorable physiques in professional wrestling of the 1950s. A competitive bodybuilder before he ever got into the grappling game, Melby carved out a headlining career in whatever territory he appeared in.

Yet his death on July 14, 2019, in Salt Lake City, Utah, made no headlines. There was no obituary in the newspaper despite his fame, nothing listing his accomplishments in 92 years on this planet.

Born May 12, 1927 in Salt Lake City, Utah, Arnold William Melby Jr. was active as a youth. His father was an avid skier and encouraged Bill to be physically fit. At Granite City high school in Salt Lake City, Melby won a city wrestling title. He also got into weightlifting as a teenager, training at the LoZan physical culture studio, and was winning contests by 1948. Among his titles were Mr. Utah and Mr. Pacific Coast, and he finished third in a Mr. America competition.

He got some press in the Salt Lake Telegram in April 1947. “A newcomer to the weight-lifting competition this year is Bill Melby of Holladay, who has lifted 280 pounds in the clean and jerk already this year. Melby has been interested for some time in weight lifting as a body builder and he has competed, and placed high, in several ‘Mr. America’ contests. He is rated one of the strongest men in the state, potentially.” The local papers would continue to cover his weightlifting competitions.

Utah promoter Phil Olafsson (who had wrestled as The Swedish Angel) took notice.

“He got interested and wanted me to wrestle. I tried it and I liked it,” Melby recalled in 2006. “He didn’t teach me a lot. He just basically got me started.”

It appears that he debuted on June 8, 1949, beating Ray Stevens, at the Fairgrounds Coliseum in Salt Lake City.

Melby had done amateur wrestling, which helped. “It came real easy to me. … you either know how to move or you don’t. It came real easy.”

Pretty soon, the good-looking babyface was on the road, to Idaho, to Oregon, to Washington, before finding greater fame.

“TV was just starting, and wrestling just grew like crazy with TV,” he explained. “They sold a lot of TVs with wrestling, and TV helped wrestling.” Melby recalled that it was Verne Gagne who recommended him to Chicago mat men Fred Kohler and Jim Barnett, who ran the TV show that was seen across the continent, from the International Amphitheater or the Marigold Arena.

“I guess most of my action was out of Chicago. Of course, when you were out of Chicago, you were all down the east coast, and a little bit of Canada, and the Midwest,” Melby said. Such was the strength of the Dumont network: “Wherever [it] went, we went.”

Melby was one of the most recognizable mat stars. “I’d walk down a street in a town I’d never been in, and people would say hi to me. That’s weird.”

It wasn’t just the TV exposure, either. He was easy copy for the newspaper men: “popular and handsome wrestling heavyweight from Salt Lake City”; “Bill Melby, one of Utah’s greatest big time wrestlers”; “Melby, who sports the features of a movie star.”

Always a babyface, Melby would defeat his opponents with his Cobra Twist: “a hold that can numb the stomach muscles if the opponent does not quickly concede the fall.”

“I used that my whole career,” Melby said of the modified abdominal stretch. “You hook the leg, and you’re in the back of them. Then you hook under the arm of the head and just twist them. It twists and stretches their abdominals. That’s a good-looking hold, and it’s an amateur hold too.”

Perhaps Melby’s best-known pairing came alongside Billy Darnell, in 1953-54. The two young wrestlers with the carved-from-stone physiques were in demand everywhere in the country as NWA World tag champions from the prominent Chicago promotion.

“It was a hectic year. That’s the thing that really sticks out in my mind,” said the late Darnell, a New Jersey native, in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Tag Teams. “Usually you’d be in one territory for while and then move on. We were booked in one territory this week and another territory the next week. And we drove; we didn’t have superhighways. I was based out of my car, living in a hotel, but based out of a car.”

Darnell and Melby got together at the hand of Barnett, who saw box office appeal in a young, good-looking tag team. The tandem beat Lord James Blears and Lord Athol Layton for the Chicago World titles in October 1953, then swapped the belts with Ben and Mike Sharpe.

After a year on the highway, Melby and Darnell jointly agreed to take a hiatus. “We were traveling in Bill’s coupe on roads going 85 mph so we could get to town and get some sleep, get to a gym and work out,” Darnell said. “That wears you down.”

Peers recalled Melby as an easy-going sort.

“He was a guy that always had a hello for you, he always had a handshake, and he had a friendly attitude about him,” said Stan Holek, who worked as Stan Neilson and Stan Lisowski as well. “He did his job quite well. He was quite athletic. He was a good looking guy. He had it all going for him.”

“Bill’s a good guy. He’ll give you an honest opinion of the business,” said “Handsome” Johnny Barend. “He was a good performer and everything else.”

Melby concurred that he didn’t rock the boat. “I was just going along with the program, and making money was something I liked.” Part of the groundedness came from the fact that he generally had his family with him in the dozen or so cities they lived in.

His last prominent run was in 1960, as Roy Shire started promoting in San Francisco. Melby was key for an angle with Mitsu Arakawa, where he so tightened his abdominals that Arakawa couldn’t use his famed stomach claw.

“When Roy first opened that territory, when he kind of forced Malcewicz out, Bill Melby was semi-retired and wanted to get out of the business,” recalled “Moondog” Ed Moretti. “Roy convinced him to stay on and they built him up to be a big, big star. He was Roy’s first real babyface that was kind of hanging around the area, along with the Brunetti Brothers, a tag team.”

In 1965, Melby stopped wrestling completely after a part-time schedule, moving into real estate. “In the early ’60s, I started building apartments. I ended up with about 72 apartments. I’d build them all, maintain them, run them myself, my wife and I did,” he said, adding that the last batch was sold in 1998. “When I discovered real estate, that just really interested me and I just went all out on that. You’ve got to find something that piques your interest.”

“I was always a saver. I didn’t end up with a lot of money out of wrestling. It took me a while to make the transition to be a saver. But then when I got into the apartments, if you’ve got the right thinking about that, you know that you’re getting ahead every year. They appreciate by themselves, and the rents go up, and your costs don’t go up a heck of a lot. That worked out really well.”

Melby and his wife Eda — who he called Ede — had two sons and a daughter. She died in 2005, succumbing just after a heart operation. “Ede was just my whole life, and when you lose that, you’ve got your kids and friends and everything, but it’s just not the same,” he confessed of the woman he was with for 59-1/2 years.

Details on Melby’s death are non-existent other than a FamilySearch.org link that confirms all the information that had been on file, and that he died in Bountiful, a city north of Salt Lake City.