About a year ago, my passion for Houston Wrestling hit the tipping point and I started a program collection in earnest. More about that in the years to come, I hope. However, in the first big score of the collection came a twin set of Houston history: the last programs of the Morris Sigel era and the first programs of the Paul Boesch era.

I grew up on Paul Boesch’s Houston Wrestling. As a journalist and nascent wrestling historian, I strive to never think I know everything. However, quickly with Morris Sigel, I realized how much there was I did not know. (Donald Rumsfeld called this a known unknown!)

At the same time, I was watching the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame process play out from afar, tracking the trends on the HOF Tracker and rooting for my guy, the Junkyard Dog. I couldn’t help but notice Morris Sigel there, somehow not in the first class of gimme, no-brainer Hall of Famers, somehow not getting in again last year.

I wanted to do something for him this year. So, with a newspaper.com account and a list of books I had read once without ever noting the name Morris Sigel, I read and reread everything I could find. To be honest, after a year of research, I am even more amazed Sigel wasn’t put into the Hall by decree in its first year. However, I hope this year’s efforts land him and JYD in the Hall (along with Paul Orndorff, who came so close last year, he doesn’t seem to need a hand), so I can move on to helping Bull Curry’s HOF credentials, and do some more research on Whiskers Savage and also the 1950s Texas wrestling war.

Whiskers Savage

This spring, I wrote a seven-page talking points memo for Sigel’s candidacy in the non-performer category. In addition to the newspaper research, my paper was shaped by books by Peter Birkholz, Tim Hornbaker, and Lou Thesz, listings on Cagematch, Wrestlingdata and Ain’t It Cool, and discussions with wrestling historians. Greg Oliver, Al Getz, Mark Coale, Mike Sempervive and Lance Peterson, among others, got editing cracks at those notes, and Steven Johnson was called in for his expertise and research on tag teams, as well. I am grateful to all of them for their time and knowledge.

Twice SlamWrestling.net asked me to share my ideas in a guest column, and now that it is Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame season, I am honored to do so. Instead of reprinting those notes, I have summarized them into a few categories:

Houston Wrestling

Houston Wrestling began in 1916. The Sigel Brothers, Julius and Morris, New York natives who moved to Houston as teens, got involved soon after. Morris also worked at a lumber yard for more than a decade, but when he got laid off, he turned to promoting full time. He and Julius took over the business in the mid-20s but Julius left for Shreveport before decade’s end. Morris then promoted Houston until his death in 1966.

Morris Sigel

Morris Sigel was the first person licensed to promote wrestling and boxing in Texas. Decades later, he was the first promoter to be honored by proclamation by the state legislature.

In 1953, Houston Post columnist Harold Young wrote about Houston Wrestling:

Mr. Sigel figures that he has had six million paying customers in 38 years and has staged at least 7,500 wrestling cards. Only two Sigel shows have been canceled. Once when the bayou flooded clear up to Travis Street — Sigel customers bear with him in many things, but he has never tried to cajole them to take a rowboat to the City Auditorium.

And the week Texas City blew up, he canceled. It was too appalling even to think of going on.

The end of the Sigel-McLemore feud in May 1954.

Texas Wrestling Agency

The success of Houston Wrestling inspired a Texas circuit. Set up in the 1930s, Sigel, Karl “Doc” Sarpolis and Frank Burke owned the agency, which developed local promoters across a huge stretch of Texas, from Corpus Christi to Wichita Falls.

Several times, allies and friends, wrestlers and other promoters, tried to take away Sigel’s promotion or booking agency. In fact, Sarpolis and Dallas promoter Ed McLemore tried to take the booking office twice, leading to the Texas wrestling war of the 1950s. Sigel prevailed every time. He lost a few battles but won every war. There were at least three suspicious fires during these wars, including the Dallas Sportatorium burning in 1953. By the end of that year, McLemore was just hanging on in Dallas and losing everywhere state wide. The NWA intervened and forced a truce in 1954. (Upon Sigel’s death, McLemore, with Fritz Von Erich‘s help, finally took the booking office).

The Sportatorium burns down in May 1953.

Sarpolis seemed to get out of wrestling for a short span before buying the Amarillo territory the next year.

Sigel, McLemore and Sarpolis all died in the late 1960s. All three were eclipsed by their proteges, Boesch, Von Erich and Dory Funk Sr., respectively. However, forgetting Sigel is probably the biggest wrestling history blind spot, given what he did for Boesch.

Paul Boesch starts promoting in Houston in February 1967.

Paul Boesch

A wrestler and World War II hero, Boesch returned home safe from war, only to suffer a career-ending car accident before the end of the decade. Sigel hired him and made him the voice of Houston Wrestling, first on radio and then on television. Boesch worked for Sigel for more than 16 years and bought the promotion from Sigel’s widow in 1967.

Boesch wrote this tribute to Sigel:

Morris’ strength as a promoter lay in his ability to bring good business practices into the sports world. He paid his bills promptly and had an unparalleled reputation for honesty. … From the beginning of Sigel’s promotion, Houston fans saw the best wrestlers in the game.

The thing I love about that tribute, is it is exactly what most people in the business ended up saying about Boesch. Despite the nice guy label, it isn’t true that everyone in the business had good things to say about Boesch — Gary Hart, Jim Ross and Bruce Prichard all had their moments with him, certainly — but overall, his reputation is as an honest promoter, a fair payoff man, and a good businessman, with deep ties to his city and state.

Boesch sounds a lot like his mentor, doesn’t he?

In fact, just about everything I remember and love about Houston Wrestling in the Boesch era actually started in the Sigel era. Weekly Friday shows, with a storyline emphasis on making attending a regular habit for the fans, began in the 1940s. Houston Wrestling got TV in 1949, and when showing full shows live hurt ticket sales, the promoter reinvented the broadcast, switching from live shows to taped ones, creating a formula Birkholz described as a TV show meant to “tease” and a live show meant to “please.” The promotion started running the Sam Houston Coliseum as its main home in the 1960s, and 1965 is the year it really pops, as Von Erich became a huge star in Houston. The promotion briefly lost TV in 1966, when ABC 13 had too many network obligations to run the show regularly. Before Sigel’s death, Houston Wrestling signed a deal to move to KHTV 39 (39 Gold), where it aired for the rest of its run.

Of course, Boesch wasn’t the only person Sigel helped or influenced.

Lou Thesz, Buddy Rogers, Fabulous Moolah, Ric Flair, Woman Nancy Sullivan, Rick Rude and John Arezzi at the 1991 Weekend of Champions. Photo courtesy John Arezzi

Star-maker

Herman Rohde became Buddy Rogers in Texas. His first title was the Texas title Sigel and Sarpolis created.

After learning about a phenom from South America, Sigel gave Argentina Rocca his first break in North American. Rocca ended up jumping to New York and no-showed a string of Texas matches. For about a year, Houston and New York argued over Rocca returning to make restitution. Finally, Sigel got Rocca’s license suspended in Texas, and began to campaign for the suspension to be honored in the northeast. Rocca returned to Texas in 1949 to put over Lou Thesz and Leroy McGuirk.

Verne Gagne in Houston in 1949.

Verne Gagne was an amateur with just a handful of professional matches when he arrived in Houston in 1949. His first title was the Texas title. Birkholz said Sigel strapped it around Gagne’s waist himself.

In his book, Hooker, Thesz said something interesting about Gagne’s early career:

Verne once told me he came close to getting out of the business at the time because he wasn’t making any money at it. What changed his mind, he said, was a date we worked together in Houston, in the fall of 1950, where Sigel paid him $900. He said it was the first time he had made any real money, so he decided to stick it out.

Can you imagine wrestling without Verne Gagne?

How about Gorgeous George? Sigel discovered George Wagner busking on the streets of Houston, challenging people to fights for money.

George Wagner.

Adnan Al-Kaissey was a football player at the University of Houston that Sigel recruited into wrestling, along with his teammate Hogan Wharton. Wharton was the bigger star at first, but he ended up playing in the NFL for the Oilers. As Billy White Wolf and then Sheik Adnan, Al-Kassie had two great runs in the business.

And while Lou Thesz was fully formed when he met Sigel, there is a curious note in the Hornbaker cannon about the history of wrestling and the NWA cartel. Thesz and his dad were promotional rivals to Sam Muchnick in St. Louis, and Thesz was a rival world champion to the NWA’s Orville Brown. While the NWA was courting Sigel and his Texas allies, a historic partnership was forged in Houston. Thesz and Muchnick happen to be there the same day, and it was Thesz who asked for a meeting.

In 1950, Houston hosted the NWA convention. Muchnick was elected president and Sigel vice president. When Brown was injured, Thesz became the NWA champion. And while Thesz seemed to always have had an uneasy alliance with the Alliance, there was a period where Sigel appeared to be the peacemaker.

And did I mention the ultimate Depression-era babyface, Leo Daniel Boone “Whiskers” Savage? Perhaps I will tell his story another day.

Innovator

Actually, remember Whiskers?

Savage and Milo Steinborn lost to the evil Hindu Brothers, Tiger Daula and Fazul Mohammed, in a Texas Tornado match in Houston in 1936. It was the first team match in Texas history, just a year after a Milwaukee tag team match Johnson has flagged as the first known tag.

In 1950, Sigel brought the Parade of Champions concept to Houston, filling up the Coliseum for a special event. (Buffalo apparently was the first to run a PoC, way back in 1939.) Parade shows became a special event concept Sigel continued to use, including sending it to other markets. In 1961, a Parade in Houston had all title matches. To celebrate McLemore’s 22th anniversary, Dallas ran the Parade show 11 days later, with almost the exact same card.

It is hard to say in wrestling who invented what or who did something first. However, Houston Wrestling during the Sigel era featured cage (“fence”) matches, animals, “lights out” matches, battle royals, mixed tags, integrated matches, loser-does-something-embarrassing matches and two-ring matches. Because Houston Wrestling typically ran only 50 weeks a year under Sigel, the first January show became a big, heavily promoted event. The use of battle royals, two-ring battle royals and two-ring team matches in Houston all began under Sigel as a way to hype the annual restart of the promotion and lure fans back to their weekly attendance habits.

A Morris Sigel combination show with wrestling and the symphony.

Civic pride

Sigel’s Houston Wrestling was a part of the community. He raised money for Leader Dogs for the Blind after McGuirk lost his eyesight. Sigel sold war bonds during WWII, even staging a event featuring wrestling and the Houston Symphony Orchestra. Young and the Post reported the efforts led to Houston Wrestling selling $30 million in war bonds.

Sigel was known for his charity work and his involvement with local organizations, especially those for troubled kids. If you look at the work of Sarpolis in the Amarillo territory and the people his charity work influenced — Funk Sr., Eddie Graham, Bill Watts — you can trace some of that back to Sigel’s example. Obviously, the same can be said for Boesch’s deep ties to the Houston community.

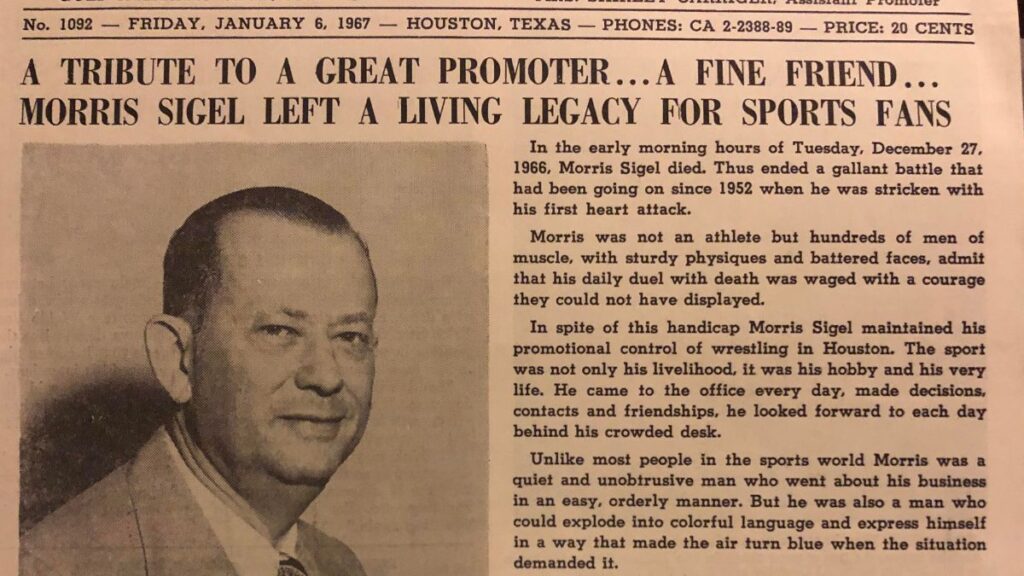

The tribute program after Morris Sigel’s death.

Conclusion

I could go on. Believe me I like going on, but I think I have stated Sigel’s case already. His protege is a Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Famer for a career essentially half as long, and the successful formula for Houston Wrestling was set long before Boesch bought the promotion.

Morris Sigel is the forefather of Texas wrestling. He is partially responsible for several of the greatest wrestlers and some of the most innovative promoting concepts of the 20th century. Few promoters drew as many fans to as many shows as he did, or promoted successfully for as long as he did. The Houston Wrestling he created is remembered fondly to this day, often associated with his protege.

So, please vote for Morris P. Sigel in the non-performer category for the Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame.

RELATED LINK

Greg Klein is an actor-writer-producer who lives near Cooperstown, NY. He is the author of three books, including the Junkyard Dog biography, The King of New Orleans. (Vote JYD!) He is the film commissioner for Otsego County, NY. Although he grew up in suburban Maryland, he spent his summers and holidays at his dad’s house in Houston, where Houston Wrestling at the Sam Houston Coliseum changed his life. He also was a professional wrestler for a few years in the 1990s, trained by Adrian Street and mentored by Jerry Grey. He has a podcast, Greg Klein’s Old School Rasslin Talk, where he mostly talks about southern rasslin.