It’s impossible not to start at the end for Dennis Clary, his death coming in the ring just six years into his promising wrestling career.

Yet it wasn’t a wrestling-specific fatality, but instead a brain tumor that had been lurking and chose the Tucson Sports Center on Thursday, January 27, 1955, to make its presence known.

Clary was in the ring against Ali Bey (George Stefanides), whom he’d faced numerous times. The match had only just begun, the babyface Clary flinging his rule-breaking opponent against the ropes, when he collapsed.

It wasn’t part of the script.

Medics were summoned, and Clary was taken to St. Mary’s Hospital in Tucson, Arizona, where he died three days later, on January 30.

Clarence Vincent Lizdenis – Clary’s real name – was 32. His body was returned to his native California, where he was tended to by Reilly’s Funeral Home and a service held at Chapel of the Oaks in Oakland.

* * *

Born on December 28, 1923, to Vincent Lizdenis and Alfrida Medeiros, young Vincent—he never went by Clarence—grew up with a brother, Brian. Little is known about his early days, though some of the promotional material for his wrestling matches note that he “had hopes of becoming a concert violinist during his childhood days. Then he became a saxophone player with a Los Angeles dinner club orchestra.” Apparently, he could also play the clarinet as well. For sports at Fremont High School in Oakland, he played football, basketball and wrestled.

There are numerous references to Lizdenis serving with the Army as a paratrooper during World War II.

Post-war, Lizdenis seemed to focus on his conditioning and became a veritable Adonis, a 220-pound beach-loving workout fiend espousing the benefits of a healthy diet, before entering professional wrestling in late 1949.

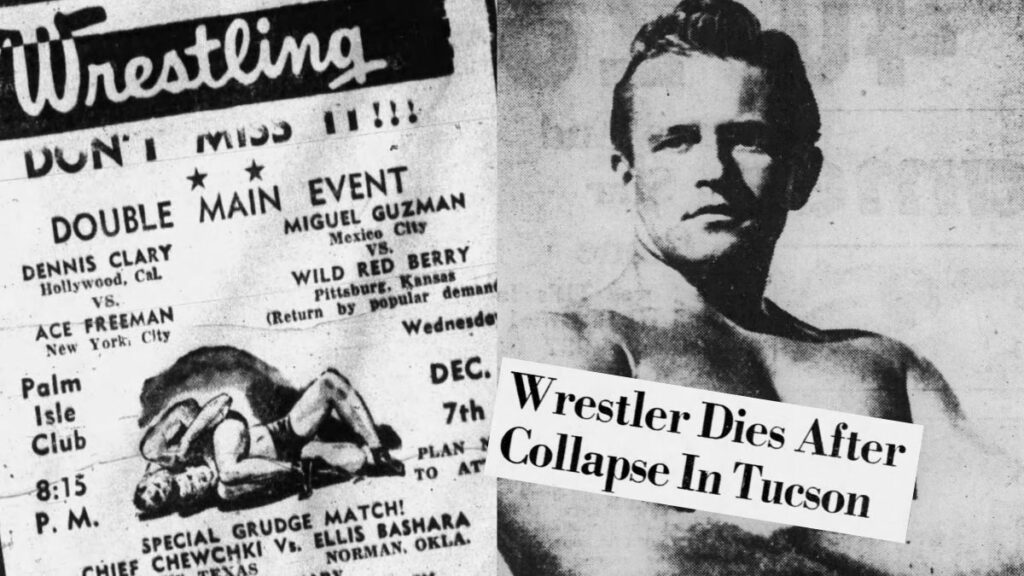

Early in his career, Dennis Clary was already a headliner. This card is from Longview, California, on December 7, 1949.

Naturally, that attracted attention from Hollywood, or so the story went. In the St. Joseph Gazette, on December 22, 1950, columnist George Sherman wrote that:

Dennis, according to Promoter Gust Karras, had a promising future in the films but decided he didn’t like the Hollywood way of life in which a fellow’s chief exercise consists of pushing a blonde around nightclub dance floor.

His hobby of daily exercises and a rigid diet just didn’t fit in with the flighty life of the flicker folk. So Dennis and the movies parted company.

The Longview News Journal on November 29, 1949, had something similar: “Dennis Clary—the Hollywood, Calif., Adonis. Clary, who owns one of the finest physiques in the country, turned down a motion picture contract in favor of the wrestling pastime. He is one of the most handsome men in sports and should prove a great favorite with the feminine fans.”

Hitting the road out of California, the newly rechristened Dennis Clary is on cards on Texas, where he is called “the Irish physical ed instructor”, before heading east, wrestling into Ohio, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and even down to Kentucky.

Dennis Clary, circa 1950.

He lived up to the hype—”has been a professional wrestler only for a year but is already reported as farther advanced than many grapplers who have been in the game much longer.”—in St. Joseph, Missouri, and found a mentor.

Gust Karras, who promoted the territory, saw something in Clary, and started him off with a draw with the star Tarzan Kowalski (the future Killer Kowalski), leading to the newspaper writing, “He should make a strong bid for the No. 1 position locally.”

The former NWA World champion, Orville Brown, who had been injured in a 1948 car crash and was forced to relinquish the title, met Clary, and, in May 1951, it was announced that Brown and Clary had agreed to “a new 5-year contract calling for Orville Brown to serve in the full capacity as his coach and business manager.” There is, however, little detail on the contract and little comes up down the road connecting Brown and Clary.

Dennis Clary and Orville Brown. Courtesy Chris Swisher Collection

Instead, Clary was on the road again, California and back to Kansas. In October 1952, Clary won the Pacific Coast tag team titles with Rikidozan in San Francisco’s Winterland Arena. Rikidozan — sometimes billed as Riki Dozan in the US — would become the cornerstone of Japanese wrestling when he imported American wrestlers in 1954, though Clary never did wrestle in Japan.

Clary was also in Hawaii for early 1953, with promoter Al Karasick having ties to both San Francisco and Japan.

A year later, however, and Clary was back in California—on trial.

* * *

Nestled in the agricultural San Joaquin Valley, Visalia was a small city south of Fresco, that saw wrestling on occasion, promoted by Louie Miller out of Oakland. The Visalia Municipal Auditorium hosted a show on the night of June 23, 1951, with Wild Red Berry against Danny McShain in the main event. During the bout, Clary came out to challenge the winner. Chaos ensued, and Berry won by countout in the third fall.

Mrs. Dorothy Mae Berri filed a personal injury suit after she ended up in the mix, on the floor under the wrestlers. She asked for more than $120,000 in damages, from Miller, McShain, Berry and Clary. Wearing a neck brace in March 1954 as the trial began before Judge Cecil Edgar, Berri, a mother of four and aged 28 at the time of the trial, testified that her memories of the night were “vague.”

Miller took the stand, as recounted in the Visalia Times Delta:

He said that there was a crowd of women attempting to hit wrestler Danny McShain. He said McShain was leaving the area of the incident with two Visalia police, whom he hired as floor guards for the evening.

He related that that sort of occurrence is not unusual at a wrestling match.

Miller stated he was acquainted with Mrs. Berri and her husband and had noted their presence in the front row seats prior to the start of the evening bouts. He stated also that later in the evening he observed them sitting “about five rows back from the ring.”

He said he didn’t note anything unusual, but in passing asked them “what was the reason for them sitting there,” to which he said Mrs. Berri stated, “There is too much commotion up there” and pointed in the direction of the seats they sat in at first.

Berri ended up under the wrestlers, and testified: “I don’t know what happened. McShain fell on me. I was on the floor. When I was on the floor I saw Clary. I couldn’t get up. They were fighting. Then somebody picked me up and took me to the water cooler at the side of the building. I remember leaving the building with my husband and another man, one on each side of me, and we went home.”

On the second day of the trial, it was announced that Miller and Berri had settled, her claim against him as promoter dismissed. Though not divulged until after the trial, Miller paid $3,750, $550 to Berri and $3,200 to his insurance carrier.

Also on the second day, Berry took the stand. Berry stressed that there was “no fix” in wrestling matches, and said that he and McShain were not friends, but that he was “a business competitor.”

The Times Delta detailed an exchange:

[Berry] said it was an unwritten law of the business that wrestlers shall not abuse spectators, adding: “But there is no rule the other way around.”

“You are not supposed to strike spectators?” queried [plaintiff counsel Roger] Walch.

“Supposed?” he snapped with rising impatience, “you just don’t.”

Dr. John Pace, of Fresno, took care of Berri and said that she had been hospitalized from early June 1951 until early October. Wrote the Times Delta: “He testified under cross examination that Mrs. Berry’s nervous condition could have been caused by female disorders, resulting in the operation she stated she underwent while a patient in the hospital but that in his opinion her physical condition was result of injuries received when the wrestlers allegedly fell upon her.”

On the Friday, Clary was on the stand, and admitted that he “pulled McShain from the ring with the help of others.” McShain himself followed and confessed that he did not know who it was that initially pulled him from the ring.

After a weekend recess, the case continued, and Berri made a spectacle, having near-fainting spell and “as she left the witness stand she unsteadily moved along the jury box rail with her hand covering her eyes.” Later on the Monday, the case against Wild Red Berry was dropped.

The next day, Tuesday, March 10, 1954, the case came to a conclusion, and the jury of six men and six women debated from 5 to 8:30 p.m., ruling that Berri was entitled to nothing. The key was defense counsel, Noel H. McDermott, in his closing argument, saying that a “spectator at a wrestling match is familiar with the possibility of the contestants carrying their battles to the floor or being pitched out of the ring into their laps.”

The headline in the Visalia Times Delta on Wednesday, March 10, 1954.

In retrospect, the case is fascinating for a few things—and not just Berry apparently reciting Shakespeare while on the stand. For one, a defense counsel for the wrestlers was Robert Eaton, son of Los Angeles wrestling and boxing promoter Cal Eaton, and Robert was married to Marilyn Knight, the daughter of then-California Governor Goodwin Knight. The kayfabe denial by the wrestlers was true to form as well.

And it ended the way a wrestling trial should, as the Times Delta reported:

In the wrestlers camp jubilation at being absolved of blame broke forth in sophomoric hilarity.

The wrestlers grabbed their counsel, Noel H. McDermott, Visalia Judicial District Judge, who took leave from the bench to try the case in superior court, hoisted him to their shoulders and mauled him affectionately as they marched back and forth in the hall outside the court.

Weeks after the trial, Berry faced Clary in Wichita, Kansas. Though the trial wasn’t mentioned, the hype was on point, with former heavyweight boxing champion as the referee. Reported the Wichita Eagle:

The decision to rush Clary here will probably come as a surprise to many Wichita mat fans. However, Dennis was a tremendous drawing attraction here two years ago and competed in a score of featured contests in the local arena.

Matchmaker Orville Brown said that he decided to call on Clary for a return here because the Forum patrons “have all wanted to know when Dennis would be back here and I believe there’s no time like the present.”

Brown added that he thinks the matching of Clary against Berry will produce one of the season’s best mat events. “They both are clever strategists in the ring and great crowd pleasers,” the matchmaker remarked.

* * *

Dennis Clary promoted as Mr. California in a promotional photo, circa 1950. Courtesy Chris Swisher Collection

Immediately after the in-ring incident with Clary during the bout with Ali Bey, there was discussion on what happened.

Promoter Rod Fenton stressed that Clary collapsed “with not a blow being struck.” Previous bouts were examined including one from the week previous, where Clary didn’t even have a match, the villainous Don Evans having attacked him before the bell.

There was an Associated Press report that Los Angeles booking agent Pat O’Brien had said that Clary had trouble passing a recent physical in L.A., but that X-rays followed and he was allowed to compete. Fenton himself said that Clary had been looked at by three doctors in three different cities (Phoenix, El Paso and Tucson) before his matches in the territory.

At the time, Arizona did not require boxers or wrestlers to undergo any kind of a physical examination before competing, and there was no state athletic commission. A few politicians used Clary’s death to try to change that, noting that there was no way of knowing about the brain tumor.

Back in St. Joe, where he’d been on top as the Heart of America champion, Karras praised Clary as a “very good wrestler and was popular with the fans.”

“I’m very sorry to learn of his death,” said the St. Joseph match maker. “Dennis was a steady performer and a real gentleman.”