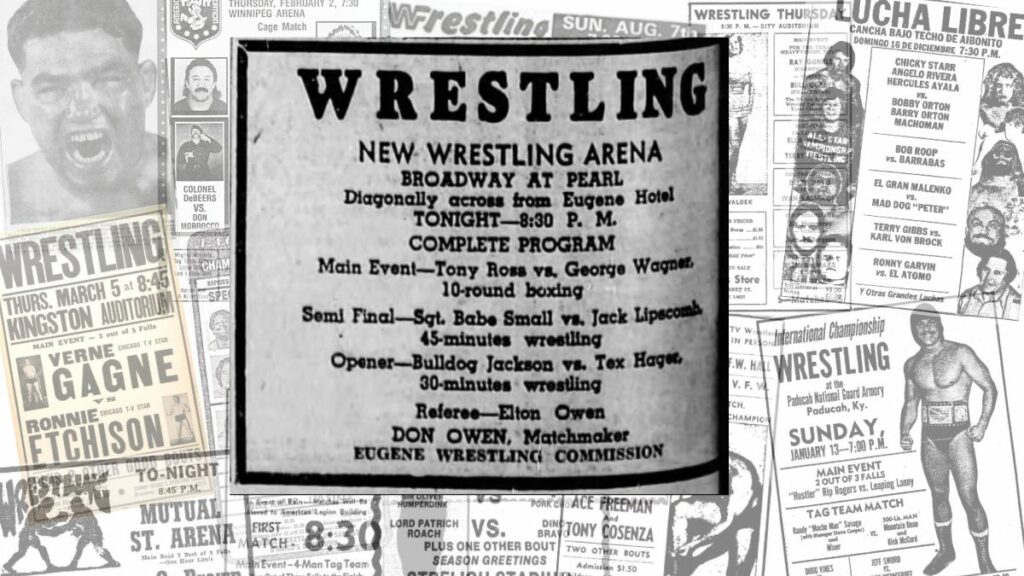

Hi, all. Welcome back to another edition of Card Exam. This time we’ll dive into a strange card from Oregon in early 1943. This was the year’s inaugural show in Eugene, with local promoters Don and Elton Owen keen to boost their business fortunes heading into a new year. Here’s the lineup and results.

January 14, 1943, at the Pearl Street Arena, Eugene, Oregon.

- Tony Ross def. George “Crybaby” Wagner via KO in round 3 of a 10-round boxing match

- Sgt. Babe Small vs. Jack Lipscomb, 45-minute time limit draw

- Tex Hager def. Bulldog Jackson

This card is unique for a few reasons. First and foremost, this is a very early example of a card promoted by Don Owen. While Owen had started selling popcorn years earlier, by the early 1940s, Don and his brother Elton began promoting shows in their hometown of Eugene, including this card at the Pearl Street Arena.

If Don was a natural at promotions, Elton was more geared towards getting in the ring, usually as a referee. But Elton never shirked physical confrontation, due in no part to his impressive background in football, boxing, and even as a wrestler, having debuted in 1938.

Elton Owen.

Elton had lengthy, bitter feuds with the two men he was refereeing in this main event – Tony Ross and George Wagner. Owen feuded with Ross in 1942, eventually getting the better of the gruff grappler, before turning his furies on the “crybaby,” George Wagner, later in 1943.

But getting back to what makes this show an oddball – the arena where it took place is something of a mystery. There’s very little information on the Pearl Street Arena (sometimes styled the Pearl Arena), but that’s likely because it had a very short wrestling shelf life. Initially opened in the summer of 1942, Don and Elton Owen had switched venues to the larger Eugene Armory by the end of 1943.

So what was the problem with the new arena on Pearl Street, in the heart of Eugene? It seems the costs of running the building and its reduced capacity were a headache for the Owen brothers, who sought better returns almost immediately.

An August 1942 story in the Eugene Guard highlighted the Owen brothers’ concerns. Owen explained that a “combination of circumstances have caused him to boost the prices, including higher rent and limited seating capacity at the new Pearl Street arena, and increased travelling expenses of the wrestlers. Repairs to the building, including ventilation and toilet facilities, have placed a financial burden on the matchmaker. And in the near future, he will add a modern public address system and more adequate seating.”

Despite the price increase, Eugene fans still paid half of what Portland fans were charged. Still, finances were tight, and Don was realistic: “I hope to bring some outstanding attractions to Eugene soon, and unless the revenue increases, this would be prohibitive,” Owen said. Judging by the short stay at the venue, revenues did not increase.

That’s not to say the brothers were running boring shows – far from it; but in terms of quantity, they were lacking. Take this three-match card to start the year: the two wrestling matches comprised a total of 70 minutes of wrestling, with the 10-round boxing match not going the distance.

That 10-round bout, a grudge match, pitted Tony Ross and the “Toast of the Coast” himself, George Wagner. Wagner had already begun wrestling under the Gorgeous George name, having already won the West Coast World title and adopted some of his preening and primping, he retained enough of his original character for the Oregon fans to root him on, at least in the short term.

Writing on his return to the area in the summer of 1942, the Guard said that Wagner showed “crybaby tendencies, but his refusal to fight fire with fire won for him some of his lost popularity before the match ended.” But Wagner would quickly find himself a hated villain before the end of 1942, not just because of his Gorgeous George gimmick. Instead, Wagner would defend his war record – or lack thereof.

George Wagner.

Despite his fitness, age, and profession, Wagner received multiple exemptions during the war, including a peculiar 4-F exemption, which stated he was unfit for military service for ‘physical, mental or moral reasons.’ With so many serving their country, many bristled at the thought that a world-champion grappler was physically unfit for combat. But Wagner fought back, arguing wrestlers were an “essential industry.”

“I’ll soon be in the war if that’s what you mean,” he told the Reno Gazette-Journal in August 1943, when responding to a question of if wrestlers should be at war. “I’m in 1-A now. And I’ve been in the war industry, ship building and repair, for the last two years.”

“Wrestling turns out the best soldiers.” Wagner continued. “For hand-to-hand combat, you can’t beat wrestling tactics.

“All branches of the service teach wrestling tactics for commando use,” he continued. “Jack Dempsey has a corps of wrestlers as instructors in the navy. There are wrestlers in all branches of the service.”

As noted, Wagner was handsome, for sure, but had not turned fully “Gorgeous.” His hair was still dark and slicked back, for one. He was a pretty boy but lacked the preening and pageantry. And, he needed that “Gorgeous” part, which would come soon, in Eugene no less, as Steven Verrier recounts in this Slam article discussing the Gorgeous One’s links to the Pacific Northwest:

Betty, seated at ringside at the Eugene, Oregon, National Guard Armory while George made his ring entrance and proceeded to twirl and model his blue satin robe, said to her mother, “He’s gorgeous!”

Squaring off against Wagner was Tony Ross, the villain of the Oregon mats and all-around tough customer. Ross, known as the “Toledo Terror,” was out for revenge against George Wagner. Having lost their previous matchup around Christmas, Ross sought revenge in a 10-round boxing match.

Ross and Wagner placed a $200 side wager as an added wrinkle. Local bookies also got in on the act, offering even odds for a match lasting less than six rounds and 5-to-3 odds that either Ross would knock Wagner out in less than five rounds or that Gorgeous George would get the judge’s decision.

In the end, Ross fans were happiest, with the Ohio grappler knocking George out in just three rounds. However, it wasn’t a one-sided affair – far from it, with Wagner easily winning the opening round and both men hitting the canvas. In fact, Wagner barely made it past the start of the third round before being awoken by the crowd’s jeers, the arena’s lights, and a lighter pay packet than he had hoped for.

The semi-windup for the evening pitted two more dastardly devils in a one-on-one contest. Babe Small, born Broni Smolinski, was a Portland-born rule bender currently acting as a wrestling instructor for the US Army at Fort MacArthur.

While serving, Sergeant Smolinski kept in fighting shape through his teaching but didn’t stay quiet. Like other wrestlers-turned-soldiers, Smolinski took wrestling bookings, such as this Eugene date. Beyond that, however, he also found success overseas, including winning the

Al Karasick trophy for the Central Pacific Area All-Service professional wrestling championship in 1944, as detailed in Ring Magazine (and seen below).

Sgt. Babe Small in Ring Magazine in 1944.

Opposing Sgt. Babe Small was Jack Lipscomb, current Pacific Coast Junior Heavyweight Champion, in a 45-minute non-title match. Lipscomb was another career light heavyweight, with the Indiana native earning his “Hoosier Hotshot” nickname with his temper and arrogance. The Eugene Guard noted, “As in the headliner, both men are meanies.”

That’s the final oddball thing about this card – it’s almost exclusively heel vs. heel matchups. Fortunately, that sole bout between “good” and “evil” made no mistakes in letting fans know who was virtuous – and who was not.

The virtuous? The “Creswell Cyclone,” Tex Hager. Hager was a popular light heavyweight from Texas who found success in the American northwest. Perhaps he is best known for his Tri-States promotion in northern Utah’s rugged Rocky Mountain corridor and up into Idaho and eastern Washington. Like Hager himself, the NWA promotion favored the lighter-weight classes.

Hager’s opposition for the evening was the evil Ernest “Bulldog” Jackson. And yes, I know the nickname “Bulldog” doesn’t do a great job of establishing his evilness. Fortunately, the Eugene Guard had a more fitting moniker for Jackson: “Cop Beater.”

Ernest Jackson was a wrestler of the old school, having proven himself in the carnival circuit, taking on all comers. He quickly graduated to the pro circuit, finding his greatest fame in the northwest, where he was known as the “John Barrymore of the ring” due to his handsome visage and smooth attitude with the press (and women).

Bulldog “Cop Beater” Jackson.

But if his face was pretty, his antics were anything but. Bulldog Jackson was feared for his “stomper hammerlock,” with the hold taking him to several accolades over his 31-year career.

The “cop beater” nickname is actually not as spectacular as you might think – this was no proto-Nailz. Instead, he was the victim of six Portland officers who had hauled him off to jail a few weeks prior on a drunk and disorderly charge – two officers armed with “saps.” For this beating, Jackson earned the name “cop beater.” Maybe he was a proto-Nailz after all.

A fourth bout, a preliminary matchup, was a late addition to the card but seemed to have never happened. That contest was set to pit the popular Chinese wrestler and Jiu0jitsu expert Walter Tinkit Achiu against Buck Davidson, a Texas tough guy who was another frequent face on the west coast for decades.

Cards like this are an interesting look into the early career of Don Owen, the one constant throughout the history of territorial wrestling. Owen was synonymous with Oregon wrestling for nearly seven decades, so seeing his early efforts are a great insight into the difficulties of growing a business in the depths of world war.

RELATED LINK

GORGEOUS GEORGE STORIES

- Mar. 16, 2023: IPWHF Class of 2023 both ‘Great’ and ‘Gorgeous’

- July 2, 2019: Retro review: Alias the Champ (1949)

- Oct 30, 2017: The legend of Gorgeous George began in the northwest

- Mar. 28, 2010: Hall of Fame ceremony a serious event

- Dec 1, 2008: Music Legend resurrects Gorgeous George film

- Sep. 8, 2008: ‘Gorgeous George’ tells the story of a man who struggled with fame