The best night of Don Kernodle’s life was one when he got beat. It happened August 12, 1983, when Jay Youngblood pinned Kernodle in the middle of the ring in the Greensboro, N.C., Coliseum to end “The Final Conflict,” one of the most memorable and engaging tag team feuds in wrestling history. “Kernodle was so bloody you could only see the whites of his eyes,” longtime Carolinas observer Donnie Mason recalled.

And though Kernodle and tag partner Sgt. Slaughter could no longer call themselves world tag team champions after Youngblood and Ricky Steamboat took the title, there was no question that a previously undercard wrestler had hit the big time. “I still get goose bumps talking about it,” Kernodle said more than 20 years after the program.

But then Charles Donald Kernodle Jr. was as much a fan of wrestling as he was a competitor for two decades, from a kid watching matches in his hometown of Burlington, N.C., to a notable collegiate wrestling career at Elon University to the pro game, which he loved until his death May 17, just 15 days after he turned 71.

He had his eye on the pro ranks since he first saw wrestling on TV at the age of seven. “That’s the only reason I wrestled amateur in high school and college, because I wanted to be a professional wrestler,” he said.

Kernodle started out as a heavyweight at Eastern Alamance High School before going to Elon, where he also worked part-time at Burlington Industries. He captured the North Carolina arm wrestling title in 1972 in the over-225 pound class, as well. But he indeed had his eye on the pro game, and jumped in against former Olympian Bob Roop in 1973 during a TV promotion to see who could go the longest with the star.

Though he lost, he sufficiently impressed tag stars Gene and Ole Anderson that they started training him for a pro career. “You wouldn’t believe what they did to me to try to get me to wrestle. They’d run me about five or six miles to start with and all those stadium steps up there in Charlotte. Five hundred jumping jacks. I would vomit maybe five times in the ring. They’d make you run the ropes till you collapsed.”

“I think he’ll make it. Kid’s got guts,” Ole quietly told Bob Quincy, a Charlotte, N.C., columnist who watched Kernodle do somersaults the length of a football field during one day of training.

Kernodle paid his dues, wrestling mostly in the Carolinas and Tennessee for the early part of his career. In the Volunteer State, he worked with a close friend Sonny Fargo, whom he lost one night as he went to the ring against Dennis Condrey and Phil Hickerson.

“He was behind me. … I went straight to the ring as I normally do and hell, I didn’t see Fargo anywhere. I looked up on the second tier and Fargo was sitting up there with some old woman and he was eating their popcorn,” he said. “He was waiving at me. So that son of a gun jumped up and brought the popcorn down and everything. We started beating up Hickerson and Condrey with popcorn.”

No wonder Fargo affectionately referred to him as “Kernodledoodle.”

Kernodle’s big break came when Slaughter lined him up for a tag team program, saying he was going to forge a mid-carder into an unstoppable wrestling machine. On the face of it, it seemed improbable to elevate Kernodle to that level. “Kernodle was a surprise to me. Until he teamed with Slaughter, he really didn’t have a whole lot going for him. When he got with Slaughter and they sort of jelled together, they became a good team and a good combination,” announcer Bob Caudle said.

As Kernodle recalled, he and Slaughter were on their way from Myrtle Beach, S.C. to Savannah, Ga. one Sunday morning when they touched on a subject familiar to many wrestlers. “We said, ‘Man, we need to think about something where we can make some serious money.’ ” Slaughter ran into a convenience store and purchased a small, one-course composition book. “By the time we got to Savannah, we had written that whole angle. We had a composition book full from the start to the cage match. We wrote out the whole thing riding from Myrtle Beach to Savannah,” Kernodle said.

Steamboat said the plan was perfectly executed — and the doubts about Kernodle’s record actually became a part of the program.

“Sarge had the great idea — it was all his ideas — from recruiting and going through the drill instructor, and all the G.I. stuff. Every week Kernodle would get better. This is a guy that didn’t have a win on TV. The next week or two weeks later, instead of getting beat in two minutes, it took about six or seven. Then the next week after that, he actually wrestles to a draw. Now maybe four weeks down the road, he finally gets his first win.”

Suddenly, he was Pvt. Kernodle, and a force to be reckoned with. “He was a great guy, he worked hard, and like Sarge said, it was the first time this kid was getting a break,” Steamboat said.

The blowoff match in August 1983 backed up traffic for miles in Greensboro. The end came as Kernodle and Youngblood were struggling near the ropes. Slaughter bounced into them, and special referee Sandy Scott, at the same time. He loaded up his elbow guard for a final shot on Youngblood, then placed Kernodle on top of the prone hero.

Scott, arising in the nick of time, pushed Slaughter out of the ring, enabling Steamboat to roll Youngblood on top of Kernodle. Scott recalled that when he counted 1-2-3 for Steamboat and Youngblood, “it was like a gigantic explosion.”

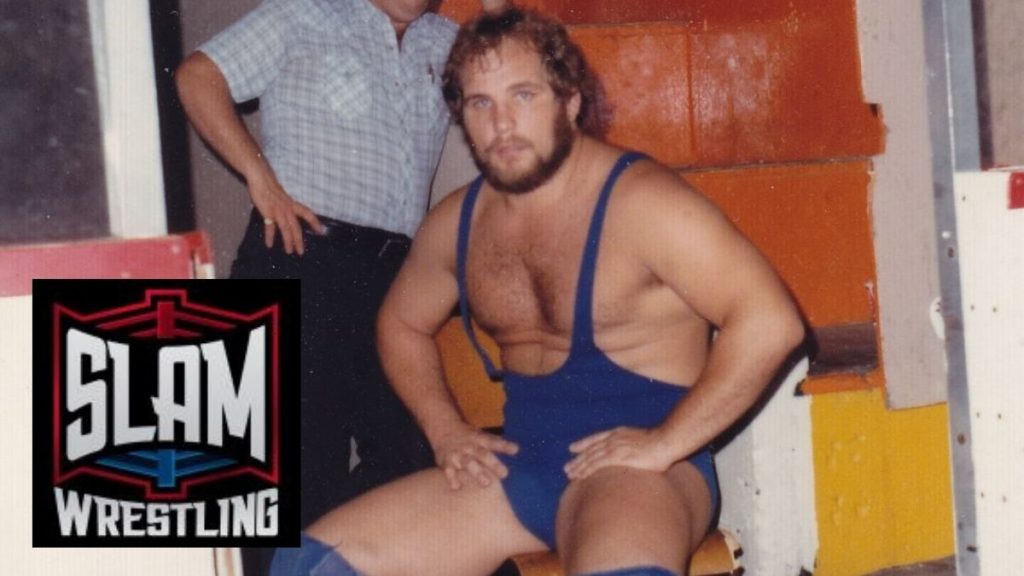

Don Kernodle with the Confederate flag in Toronto. Photo by Elio Zarlinga

Slaughter left soon after for the WWF, but Kernodle gained another big payday as “Pride of the USA” when his tag team partners, Ivan and Nikita Koloff, turned on him, administered a brutal beating in 1984, and turned him into a fan favorite for the first time in his career.

“When I got hurt that time, when the Russians turned on me and per se hurt me, I got my Daddy to come out of the top of the Coliseum to come down to the ring,” he told the Mid-Atlantic Gateway in one interview. “I told [my parents] ahead of time that I wouldn’t really be hurt, but I told them to come down to the ring.”

A change in bookers, though, quashed Kernodle’s momentum, and plans to re-team with Slaughter, though he continued to have quality matches for a few more years. Kernodle wrestled only once with Slaughter and Magnum T.A. against The Russians in March 1985. “Dusty [Rhodes] was booker and he had other ideas,” Kernodle said.

Rocky and Don Kernodle at a Charlotte fan fest in 2008. Photo by Steve Johnson

In retirement, Kernodle worked a variety of jobs, including with Immigration and Customs Enforcement with a push from old wrestling pal Johnny Weaver. He and his brother Wally, who wrestled as “Rocky” Kernodle, were staples of the Mid-Atlantic Legends Fanfest for many years.

Kernodle was to be honored in July at the Lou Thesz/George Tragos Wrestling Hall of Fame in Iowa for his pro and amateur accomplishments.