“The evidence obtained by the Oversight Committee indicates that illegal use of steroids and other drugs in professional wrestling is a serious problem that the wrestling organizations are not effectively addressing,” U.S. Congressman Harry Waxman, January 2, 2009.

Tiger Khan. Photos all courtesy Franco Frassetti and Evan Ginzburg

People yelling obscenities at each other. People getting heated over wrestling matches. Audience members getting into near fistfights. Sounds like just another night at a good wrestling show. But what is currently being described is a film screening that took place in late October in one of Manhattan’s most prestigious theatres. In this film critic’s many years of attending various film screenings all over the world, this was without a doubt one of the most passionate audiences ever witnessed. The full house at the Pioneer Two Boots Cinema on a Sunday night was debating the merits of documentary clips depicting a man that many of them had known, worked with, wrestled with, or just knew as a fan.

The producer and director fielded some praise, some abuse, and some tears after showing clips from their upcoming documentary about a professional wrestler who died too young. Friends and fans of this wrestler had come not just from New York City, but from New Jersey and Pennsylvania to see clips of it. The filmmakers themselves are no amateurs, either: producer Evan Ginzburg is Associate Producer of Darren Aronofsky‘s Golden Globe-winning The Wrestler, and director Franco Frassetti is the director of an upcoming Bruno Sammartino film. Exclusive clips were even shown from former World Heavyweight Champions, like Superstar Billy Graham. Was the documentary about Mike Awesome? Eddie Guerrero? Sherri Martel? With a crowd this size, one would at least guess that it might be an ex WWE, WCW, or ECW wrestler. One would be wrong on all accounts. The full house had come to pay tribute to the late wrestler Tiger Khan. For most mainstream wrestling fans, the question may next arise, “Tiger Who?”

Evan Ginzburg

While SLAM! Wrestling covered his death in 2006, the mainstream media had all but ignored it. After witnessing the standing room only crowd at the Pioneer Two Boots to see clips from Tiger Khan: Fire in the Blood, SLAM! Wrestling revisited who Tiger Khan was, and why his untimely passing has generated superstar like devotion. Producer and close friend of Tiger Khan, Evan Ginzburg, and director Franco Frassetti, took me on a tour of Khan’s life through New York City, from his early beginnings to his meteroic rise, and finally to where he spent his last days alive.

A TIGER IN THE ‘HOOD

Born Marlon Kalkai, Khan grew up in a lower middle class neighborhood in Queens. Taking at least three trains to reach his neighborhood from Manhattan, one enters the heart of the real New York City when exiting finally at 121st St Station. Also known as Richmond Hill, it is a vibrant multicultural community. Walking into an Indian carpet store, the Sikh shopkeeper tells us that the community is “mostly many [sic] Indians and Guyanese.”

With graffiti everywhere and litter on some side streets, Kalkai certainly did not grow up in the prettiest part of the city. It is a working class neighborhood, complete with its own steel distribution facility. The sound of trucks are deafening and heard from the small houses that line the side streets.

But Tiger Khan was far from typical. His escaping the traditional Trinidadian-American upbringing in this community seems to be an anomaly. An Indian video store that has been open for many years here contains a small section of Hollywood films and Americana on VHS. The tapes are at least 15 to 20 years old, but something unique stands out about their largest English tape selection: wrestling videos. Just minutes from the house that Tiger grew up in, he would have most certainly have seen these videos in this old video store as a child, and one wonders if part of his fascination for wrestling began then.

Where most immigrant parents would shudder with horror at the prospect of their son wanting to become a professional wrestler, Ginzburg remembers that Khan’s parents were “very supportive of his dreams. They had a huge picture of him in their living room while he was alive. They were as supportive as anybody could possibly be.”

Frassetti concurs, “A lot of the wrestlers I interviewed had no parental support. And here you have one guy who had the full support of his entire family.”

Instead of having to commute for days to find a wrestling school, as Mick Foley did, Tiger’s wrestling school was less than a 10-minute walk from his house, at the corner of 146th and Jamaica. Why a wrestling school was in the middle of an Indian community is anyone’s guess, but there it was, and its importance to Tiger’s life could not be understated. Called “The Doghouse,” Tiger would train here sometimes. He couldn’t stay away, as it was so close to him. How many other aspiring wrestlers grow up with their wrestling school closer to them than their public school? But his most significant training was at Bobby Bold Eagle’s school.We pass by a few Wanted posters that seem to be an anachronism, but a reminder of how violent these streets could be at night. “I haven’t seen posters like this since I was a kid,” Frassetti says. Criminals from outside of this community have found easy prey among the immigrants of Richmond Hill who view Gandhi as one of their saints and nonviolence a way of life. Tiger’s father, in a clip aired from the upcoming documentary, states that his support of his son’s wrestling dreams was also a utilitarian one: he wanted his son to be able to defend himself in these mean streets of Queens.

Today, however, The Doghouse is gone, and with it, a piece of Tiger’s history. Frassetti says that this is not a unique case. In his studies of pro wrestling establishments and schools in America, he has discovered that most “are now parking lots or fast food restaurants. Anywhere where there was wrestling, it has been torn down and demolished.” Frassetti looks at the the empty lot, and shakes his head in disgust.

“The A-Team” in Stampede Wrestling: Tiger Khan, Bill Yates, and Ruffy Silverstein.

THE EYE OF THE TIGER

Training with Bobby Bold Eagle, Tiger’s athleticism in the ring was noticed. Ginzburg was among the first to extol the virtues of Tiger in 1996, after they had met at a local UCW show in New York City. Ginzburg was doing play-by-play for them and then complimented him on his ability. The two became fast friends. It was at UCW, Ginzburg says, that Tiger received his big break: “Jim Neidhart and Bruce Hart came in to UCW, and they were impressed by Tiger. When UCW folded, they took Tiger with them back in Calgary. The peak of his career was in Calgary.”

Tiger’s gimmick was a stereotypical foreign heel, but in the world of wrestling, questionable presentations of minorities have always been the norm, up to the present day. Ginzburg recalls, “He was never a Face, from what I remember. He [used to say to] the crowd ‘I’m from India,’ and they’d boo him. And I thought, ‘Why are they booing India?'”

Director Franco Frassetti is playfully bullied by Nikolai Volkoff and Jimmy Snuka.

Frassetti, who has studied wrestling for decades, says that Tiger’s quick rise in the indys also reveals that he was a man with great talent. He discovered that Tiger “was so driven into succeeding. It takes, like, 10 years in the indys before being recognized,” but he was headlining around the world in far shorter time than that.

For those who have never seen Tiger in the ring, a clip from the documentary is shown with him facing none other than the Suicidal, Homicidal, Genocidal, Death-Defying Sabu. Frassetti and Ginzburg did not want to fill the documentary with wrestling clips, but this one clip stands out as one of the best of Tiger’s career, and had viewers in the Pioneer Two Boots on the edge of their seats.

But even at the peak of his career, Tiger always came back home to his parents in Richmond Hill, the dutiful Trinidadian-American son that he was. Tiger gave back to his community and never forgot his roots. His success was not without cost, however.

TIGER’S LAST SUPPER

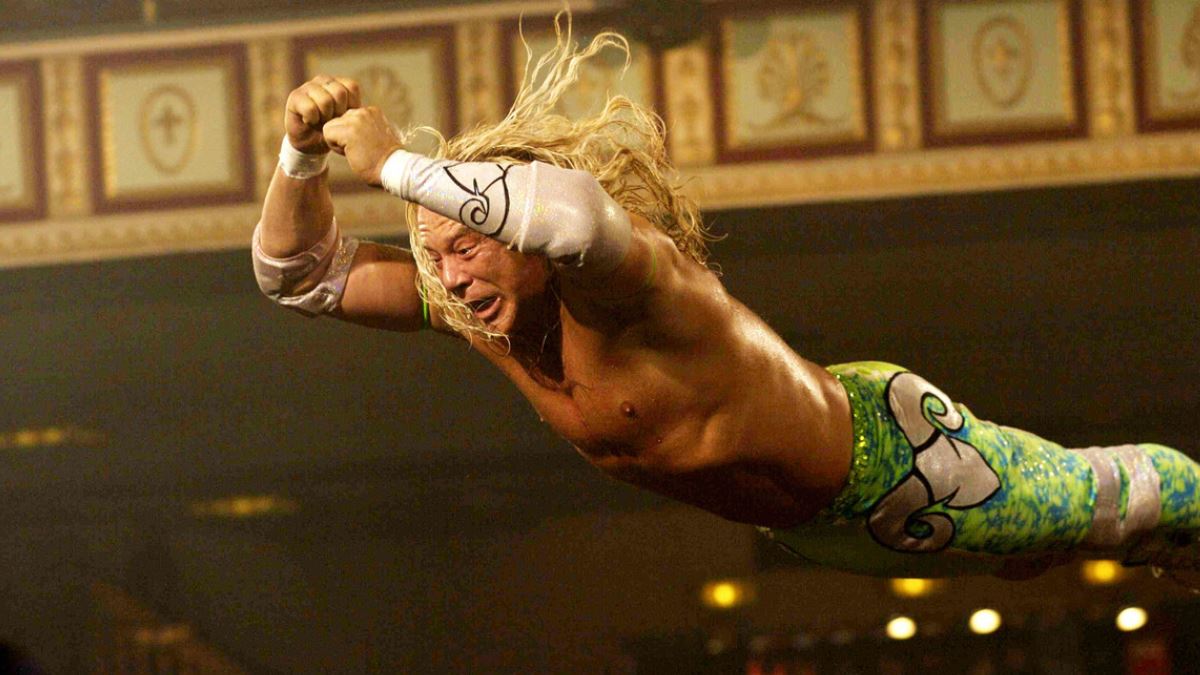

Despite Tiger’s success in the indys, Ginzburg says, he wanted to make it in the big time of the WWE. But due to his small stature (5-foot-10, 200-pounds), he was never given a chance. To compensate, Tiger resorted to what many wrestlers have resorted to before him: anabolic steroids. His Rey Mysterio Jr.-naturally-lean physique changed into that of a bodybuilder overnight. Ginzburg confronted his friend about this numerous times. “He would tell me he was cycling on, and cycling off,” Ginzburg says, “and [that he was] not doing the megadoses that killed so-and-so and so-and so, and he would rattle of the names of legends who died.” However, Ginzburg knew better, and told Tiger he wasn’t fooling anyone.

However, Tiger continued to abuse steroids with the obsession of trying to make it in Stamford, CT. When he couldn’t make it, he found other ways of coping: taking illegal drugs to cope with his depression.

Tiger moved to one of the most dangerous parts of Harlem, and Ginzburg and Frassetti next took me there to discuss the last days of Tiger’s life.

Walking in Harlem a few days before the historic election that saw the election of America’s first African-American President, it is full of life and flooded with Obama posters, sharing something in common with the Indo/Guyanese community of Richmond Hill. Much of Harlem has gentrified, Ginzburg points out, and we see white Americans, African Americans, and Asian Americans all going about their business at the corner of Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd and Malcolm X Blvd. Harlem residents can even boast of a former U.S. President having an office in their community, Bill Clinton.

But the Harlem of Tiger Khan’s last few years alive was much more violent. Ginzburg says that it was less than safe to walk alone at night where Tiger had his apartment. Drugs were more easily available in Harlem than in Richmond Hill. Tiger was also just minutes away from the all-night clubs that he began to attend more and more often as his life drew to an untimely end. “I’d be waking up in the morning to teach,” Ginzburg says, “and he’d still be in the clubs.”

Sylvia’s in Harlem

We have dinner at one of Tiger’s favorite restaurants, Sylvia’s in Harlem. All over the walls, there are photos of famous African Americans who have achieved the American Dream. Unfortunately, his unhealthy fixation on trying to make his body “big” enough to be considered by the WWE kept him from achieving his dream. Other than his family’s wall, the only place Tiger’s photo would appear again would be in obituaries.

All of a sudden, Ginzburg stops eating his meal, and remembers one of the last meals he had with Tiger. It’s almost as if Sylvia’s takes him back in time and the memory that comes back brings an instant sadness in his face. At that last supper with Tiger, Ginzburg says that Tiger got up after just having a few bites and ran out. “I had never seen him do that before,” Ginzburg remembers. “He said, ‘I have to go… get some money from someone who owes me.’ It sounded shady to me.”

Ginzburg was left to eat the rest of his dinner himself. Two hours later, Tiger returned, but with a different look in his eye. They had planned to attend a concert next, and in the middle of the show, Tiger mysteriously had to leave again. “There would be no reason to leave in the middle of dinner or a concert!” Ginzburg says with a great deal of emotion.

There was little to no optimism left in Tiger towards wrestling at this point in his life, which was extremely unusual for him. During his clean years, Tiger “would be quoting Deepak Chopra and all these guys. And all of a sudden, in the last few months of his life, he said ‘I’m not interested in [wrestling] anymore. Two months later, he was dead,” Ginzburg concludes, shaking his head, while staring down into his unfinished meal.

Tiger Khan wrestles Brett Hanson in March 2000.

TURNING DEATH INTO A CHANCE FOR OTHERS TO LIVE

Tiger’s story is sadly not unique to the world of pro wrestling, and there are many Tiger Khans, many Eddie Guerreros, many Sherri Martels. The mainstream media will focus upon these deaths for a few weeks, and then forget about them, while the large wrestling corporations benefit from the public’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. As Ginzburg puts its, “If [this many] baseball players died, it would be in the newspapers for two years. If Mickey Mantle and Hank Aaron died in the baseball business, believe me, there would be a commission.”

Ginzburg decided that he would do his best to combat this double standard when it comes to the issue of premature wrestling-related deaths. Rather than release a shoot DVD or “wrestling DVD,” Ginzburg decided that Tiger’s documentary be in an “art house” style, to attract the attention of the mainstream public and progressive media who attend art houses and film festivals. A three-disc DVD commemorating someone’s life and death put out by a wrestling company unfortunately does not reach the desks of film reviewers at The New York Times or draw the attention of investigative reporters at PBS, much to the pleasure of the wrestling companies involved, it can be assumed. Ginzburg wants to make sure the news of Tiger’s documentary does reach their desks, however.

Technically, the documentary will set itself apart from previous wrestling films, as well, as Frassetti ensured that it will eventually be made available in Blu Ray after its theatrical run, unlike the standard definition wrestling DVDs out there. “It was all shot in 1080 HD format,” he says.

Ginzburg realizes he has an arduous task ahead of him to make the general public take wrestling deaths seriously, especially after the biggest American wrestling company in the world insinuated that one of its wrestlers was found unconscious in a hotel. Despite being a storyline, a few major news corporations picked up the story as being real. Many influential individuals who have been part of the wrestling business, like Paul Heyman, felt that the angle was not only tasteless, but dangerous, in that the media will feel wrestling companies are like the boy who cried wolf once too often. Major news organizations may think twice before covering another wrestling tragedy, for fear of being worked. Once again, advantage major wrestling companies, disadvantage injured and/or dead wrestlers. Ginzburg himself was very offended by this storyline. “The recent Jeff Hardy ‘collapse angle’ struck me as not only shameless but sad. This is a company where one of their biggest stars in Eddie Guerrero was carried out of a hotel room!” Ginzburg proclaims with contempt. “Why even go there?”

Despite being Tiger’s friend, Fire in the Blood will not be a sugar-coated depiction of his life. If one can go by the clips shown at the Pioneer Two Boots in October, it will in fact be a very dark film. However, it should be pointed out that Ginzburg did not exploit his friendship with Tiger to make this film. In fact, he received the blessing of Tiger’s mother before asking Frassetti if he was interested in directing it. “I told her the last thing I want to do is anything negative about him,” Ginzburg reveals. “She was on the same page. She said if it scares one kid, it will be doing its job.” Frassetti also mentions that many people invested in the documentary, and without producers like Sandro Finamore and Reham Ahmed, “there would be no film.”

Rather than being a one-trick pony about steroids, the documentary is instead a look at how various elements caused the death of Tiger, and the role that an unregulated wrestling industry plays will be a major one. Director Frassetti, who defines himself as a filmmaker first and a wrestling fan second, ensures that the film will be an expose of the wrestling world, through the life and death of Tiger Khan.

As a filmmaker, he is not framing Fire in the Blood as a wrestling documentary. He does not want it to be pigeonholed in that limited genre. The two documentaries that have inspired him to make this one are the Academy Award-winning Born Into Brothels, and Super Size Me. Frassetti believes that Tiger Khan’s story will be taken as a story that is an archetype for all wrestlers, especially those whose employers are not doing enough to combat the use of drugs in their organizations. “The WWE made wrestling ‘entertainment’ to [possibly] bypass the steroid issue and stop paying the athletic commission,” Frassetti believes. He further points out that the company’s recent moves to ban the term “wrestlers” is an ominous one, which he believes is meant to further strip labor rights from its roster.

Ginzburg interjects, “You have a corporation that makes incredible sums of money, and the athletes are paid a minute fraction of what basketball, hockey or baseball players make. If it is a sport, then why are [the wrestlers] not being paid as much [as their counterparts in other sports]? If they are actors, then why, as actors, are they not being paid more money for being on a prime time TV series?”

Since wrestlers can no longer be called wrestlers in the WWE, both men agree that unionizing them under SAG or ACTRA is the solution. “There’s so much bad comedy on RAW,” Ginzburg says, “[but] if there’s so much low-brow humour on the show, then a [wrestler] is an actor.”

When challenged as to the fact that any businessperson will try and get the cheapest labor possible with the least labor laws, such as American companies outsourcing their IT workforce to India, Ginzburg roars, “This is not some guy sitting at a desk! This is some guy destroying his body for you!”

Both men say that Tiger Khan’s documentary will address these and many other issues. Tiger may not have made it into the giant wrestling corporations, but the documentary will point out that this was the dream he was striving for and, as Ginzburg powerfully points out, will ask if this dream to make it in those top companies is worth destroying your body and ultimately dying for. Tiger Khan did not die for the indys — he died by trying to make his body on par with the questionably muscular physiques that he saw on the highly-rated wrestling shows on TV. And in this way, he is like many others that did make it in the big companies. “He was a solid wrestler. I don’t know if it’s okay to say this anymore… like Chris Benoit [in more ways than one],” Ginzburg hesitates. “Tiger could wrestle,” but like the Canadian Crippler before him, he abused steroids and other drugs terribly. Frassetti is most animated when he talks about the mistreatment of wrestlers by the big wrestling companies. “If you watch RAW, you see their [weekly] schedule. They can’t stop for one week? They can’t give them a break?” Frassetti asks rhetorically. “If they could get a few weeks off like in any other business, then perhaps things might improve. There’s no time for these guys to recover.”

When asked if he is an anti-wrestling crusader, Frassetti disagrees strongly and responds, “Morgan Spurlock changed everything with Super Size Me, [and] I would like someone to go out there and change wrestling and make it a [safer] industry to be a part of.”

Replying to some wrestlers at the screening who demanded that the film present an overall positive vision of wrestling, Frassetti is uncompromising: “There should be a commission regulating [wrestling]. I’m not backing down on anything!”

Frassetti says that he hopes by making Fire in the Blood a film made for non-wrestling audiences, it can add to the voices calling for change in the wrestling industry. “Documentaries can touch upon subjects, and give meaning to people. I would hate to see this happen to any other wrestlers. If there’s less big guys in wrestling, and more natural people in wrestling, [maybe] this won’t happen. Maybe if the WWE considers this, it might make a difference.”

It is ironic that had Tiger lived, he would have most likely appeared in another film, and one that may be nominated for some Oscar awards: The Wrestler. The director, Darren Aronofsky, liked Tiger the few times they met and was one of the first wrestlers he met six years ago in conjunction with the project, according to Ginzburg. “Darren was very upset when he heard about [Tiger’s death]. He was sincerely upset about it. They were very close in age,” Ginzburg says. “In the thank yous to the wrestling community, Tiger is thanked at the end of The Wrestler. I’m sure Tiger would have been in it if he was alive while it was being shot.”

Ginzburg concludes, “Tiger’s dead from all of this. If this scares one kid, maybe his end would not be a total waste.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: For information on when the completed Fire in the Blood will screen in your area, please refer to the following websites: EvanGinzburg.com, Wrestling Then and Now website

THE WRESTLER (2008) LINKS

- June 17, 2009: The Wrestler still resonates with Ring of Honor

- May 23, 2009: The Wrestler ‘really got to me’: Piper

- Feb. 23, 2009: Analysis: Rourke’s predictable loss at the Oscars

- Jan. 20, 2009: Associate Producer of The Wrestler documents wrestling’s killing fields

- Sep. 17, 2008: Aronofsky and Rourke passionate about The Wrestler — and wrestling

- Sep. 11, 2008: Aronofsky’s The Wrestler an instant classic

RELATED LINKS