Rows of wrestling photographs encircle heavy-duty gym equipment wedged into the first floor of Dick Steinborn’s home in Richmond, Va., but one stands out. It’s a candid shot, a close-up in color, of a man and two kids on a sunny day at a Georgia beach. They’re grinning and carefree, and look like they can hardly wait for the shutter to snap so they can get back to the sandy fun.

The date was Tuesday, August 1, 1972. It was the last picture ever taken of Ray Gunkel.

* * *

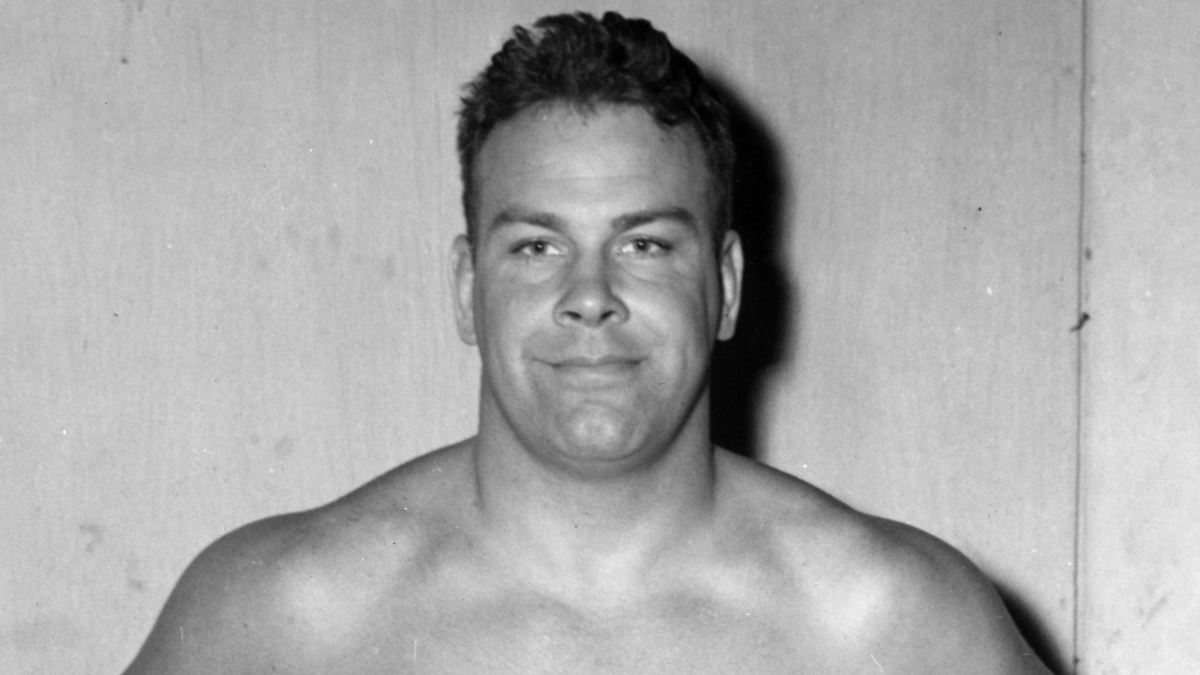

Ray Gunkel. Photos all courtesy of the Wrestling Revue Archives

On June 28, Raymond F. Gunkel will be inducted into the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame at the Dan Gable International Wrestling Institute and Museum in Waterloo, Iowa. For many fans under the age of 50, Gunkel’s name is mostly synonymous with one of the most disquieting episodes in the history of the business — a post-match death and a subsequent fray for control of the lucrative Atlanta wrestling market that combined equal parts raw emotion, martyrdom, and palace intrigue.

That, friends and family members say, shortchanges his legacy. They call him a worthy addition to a pantheon that traditionally honors wrestlers who’ve left their mark in both the pro and amateur ranks. “Ray Gunkel was a terrific guy and a good friend and a good wrestler,” said Thesz, a National Wrestling Alliance world champ instrumental in formation of the museum, before he died in 2002.

“He was a great amateur,” said veteran star Rip Hawk, who knew Gunkel and worked with him in Georgia. “He was a heck of an athlete. He was good. A little stiff, but he was good.”

Born in Chicago in 1924, Gunkel was the son of German immigrants. His father Peter was a policeman and a minor league baseball player, and that might have been the inspiration for Gunkel’s athleticism. Whether it was wrestling, football, skating, swimming, or tennis, he got a rush from competition.

“He grew up in a very modest upbringing and sports was his way to get out of the town,” said his daughter Pam Gunkel, adding that her dad initially aspired to be a teacher. “He was very driven by success. I don’t know where that came from, but from what I understand people have said he was a good guy and could be a real softie, but he was very, very serious and focused and could be really tough when warranted. That kind of came down to being extremely competitive.”

Jack Dempsey raises Ray Gunkel’s hand.

Tell that to his opponents. After Kelvyn Park High School, Gunkel settled on nearby Purdue University, where he was an All-American wrestler and football player. In his junior and senior years, he racked up a 16-0 regular season mark, helping the Boilermakers to a pair of Big 10 championships for Coach Claude Reeck. In 1947, he was NCAA runner-up to future NWA world champion Dick Hutton, taking Hutton to overtime before losing by a tight 5-3 score.

Big, fast, and strong at 6-foot-2 and 230 pounds, Gunkel captured AAU national championships in freestyle wrestling in 1947 and 1948. Like contemporaries Verne Gagne, Bob Geigel, Mike DiBiase, and Hutton, he got into the pro game almost as soon as his college eligibility expired and was wrestling for cash in Indianapolis by summer 1948. He made his first mark in Texas, capturing the heavyweight title three times in the early 1950s and earning the patronage of boxing great Jack Dempsey, who announced in 1953 that he was assuming Gunkel’s management.

“He’s the kind of guy who can carry the ball when the going gets tough,” Dempsey told the Associated Press. “Maybe I can teach him to let a few fly against some of these so-called rough guys in wrestling.” Those fisticuffs, far removed from the reversals and counterholds he used as an amateur, came in handy during a long-running mid-’50s feud with Bull Curry in Texas.

Gunkel held a variety of other titles before settling in the late 1950s as part owner and a top hero in the NWA Georgia promotion. He first appeared in Atlanta in 1953, and was a regular there from fall 1957, when he won the Southern title and International tag title (with Don McIntyre, a part owner of the territory), fighting the likes of Freddie Blassie and the Assassins, until his death.

“He was the epitome of the babyface, Mr. Do-Good, never did anything wrong, always the gentleman on the interviews,” said Bobby Simmons, who ran wrestling-related errands for Charlie Harben, Gunkel’s right-hand man and later became a referee. “I guess it helped because he owned the company, but he never lost … the hometown hero; that’s what he wound up being.”

In fact, Simmons vividly recalls watching Gunkel and top bad guy Stan Stasiak going 45 minutes around 1964. “The finish to the match was Stasiak gave up in a hammerlock. They worked that match, high spot, high spot, a little heat from the heel, comeback, and then back to the hammerlock. That’s one of the things that sticks out in my mind about him. People say, ‘Well, that crap won’t work any more.’ But it’s all about perception and he knew that.”

He also was a talented gin rummy player, said Steinborn, who was close to the family and wrestled for a while as “half-brother” Dickie Gunkel. “Two, three, or four draws from the pile, he knew what you had in your hand,” he said, adding that Gunkel at one point made more money taking suckers in card games than he did wrestling for Dory Funk Sr. in Amarillo, Texas.

A check of records shows that Gunkel slowed down his active schedule around 1965, wrestling less regularly and concentrating more on the business end, where he was known as a taskmaster, but a successful one, who had the foresight to take his TV tapings to the studios of WTCG in Atlanta, the future WTBS superstation.

“As to Gunkel and his importance here, obviously it was huge,” said historian Rich Tate, whose GeorgiaWrestlingHistory.com site is the definitive word on Peach State wrestling. “From what we know, the business here was dead before he came in ’57 and ’58. In terms of creativity, he picked a lot of that up in Texas and he brought a lot of that here. And worked with Blassie was just huge throughout the ’60s.” So successful was Gunkel that he ascended beyond the position of a local wrestling promoter to a community leader with second wife Ann.

“He was very anti-drug and just driven about being active in the community,” Pam said. “He was very generous with his money. He did everything. Community involvement was huge because of where came from, the wrong side of Chicago.” His country club-style home had, fittingly, a pool with a diving board, a tennis court, and a tree house fitted with an intercom system. “A couple of times, just to get a giggle out of us, he’d have the postman bring the mail down to my brother and I.”

* * *

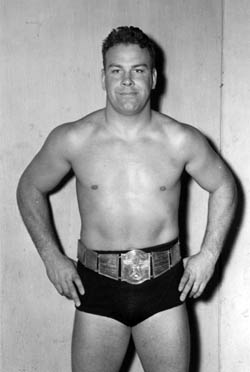

A posed Ray Gunkel.

Gunkel also formed an on-again, off-again championship tag team with Buddy Fuller, aka Edward Welch. Only a few insiders knew two things: they both owned parts of the Atlanta-based ABC Booking office and they hated each other. And that fact became a critical in the way that Gunkel’s death upended the established wrestling order.

By the early 1970s, Fuller was pushing his sons Ron and Robert, the future Colonel Rob Parker, only to find himself overruled by Gunkel. What’s more, several key players said Gunkel talked openly about bringing in Tom Renesto, one-half of the Assassins and his booker, as a business partner, further alienating Fuller.

In the summer of 1972, Gunkel, billed as Brass Knucks champ, was locked in a feud with Ox Baker, a lumbering heel indirectly involved in the wrestling death of popular Alberto Torres a year before in Omaha, Neb. The promotion billed it as murder, though physicians later said Torres died of a ruptured pancreas that preceded the bout.

On the final day of his life, Gunkel went to the beach with his kids and ate a big meal at Sema Wilkes’ famous “Boarding House” before heading to the Civic Center. “He came in the dressing room and said, ‘Boy, I ate too damn much,'” said Steinborn, who topped Rocket Monroe in the semi-final. “Then he went out there and said to Ox, ‘Lay ’em in.’ Ox hit him, he hit him hard.”

Baker’s big finisher was the heart punch, a direct blow to his foe’s heart cavity, but Gunkel overcame the battle to fell big Ox in about seven minutes. “The two had exchanged heavy blows, boxer style,” according to the Savannah Morning News. Upon his return to the locker room, Gunkel took a shower, and then sat next to promoter Aaron Newman to discuss the night’s receipts while toweling off.

A few minutes before 11 p.m., he suddenly plunged off his chair on to the floor. “If a big man had shoved him, he couldn’t have moved any faster,” Newman later said. “He straightened out and that’s all there was.” After an autopsy, Chatham County Coroner Harold M. Smith declared August 2nd that Gunkel suffered “an accidental death due to injury to his heart during the match.”

That’s hardly been the final word, though. For 36 years, wrestling magazines and, later, Internet forums, have buzzed with conspiracy theories that seem straight out of Anna Nicole Smith or Jim Morrison. How could a big meal or a misplaced punch by an oversized oaf lead to such tragedy?

Pam Gunkel has gone over the autopsy report with a fine-toothed comb and she’s satisfied with what she’s found — that her dad suffered from arteriosclerosis but that the death was an accident.

“Truly, I had the same questions myself, especially when people challenged, ‘Was it real?’ ‘Were they really getting hurt?'” she said. According to the findings, Gunkel had heart disease in the form of hardening and plaque build-up in the arteries.

As his daughter related the report, Gunkel suffered a blunt trauma when Baker flew off the ropes and delivered a blow to the chest that caused a gumball-sized hematoma to form. The hematoma swelled, then broke off and turned into a blood clot that went to his heart and killed him.

“The observations of the coroner were that he had heart disease and if he didn’t get his act together, he may have died in a few years. But the coroner said definitely that was not the cause of death, anything related to underlying heart disease.”

* * *

Ray Gunkel in action.

Gunkel’s death marked a passage in Georgia wrestling. His body was barely cold when Florida promoters Eddie Graham and Lester Welch, part of the Fuller family, plotted to take over the territory and cut his widow Ann out of the game; in fact, a friend of Ann’s overheard them scheming at Gunkel’s funeral. Jody Hamilton, Renesto’s partner in the Assassins, called it a naked power grab. “An hour or so after Ray’s funeral was over, Tom called to let me know who was there. His first words were, ‘The vultures are beginning to descend on the carcass,'” Hamilton explained in his autobiography, Assassin: The Man Behind the Mask.

Fuller, Graham, Welch and Atlanta frontman Paul Jones shut down ABC Booking and started a new venture without regard to Ann’s input or her ownership, through Gunkel’s estate, in the previous venture. “To put it in as few words as possible, what they wanted to do was push Ann Gunkel out and steal the territory. If anybody says anything different, they’re either a liar or they don’t know what they’re talking about,” according to Hamilton.

Her reaction was pure fury. She later said that she hopped into her Cadillac and drove to the cemetery in a blinding rainstorm. Her husband’s gravesite was not yet fully tended, and in the rain and the muck, she dropped to her knees and pledged, “As God is my judge, Ray, I will never let the Welchs win.”

It took almost four months, but Ann successfully formed a new promotion; loyalty to her and her late husband led virtually every wrestler in the old office to boycott a show in Columbus, Ga., on Nov. 22, 1972, nearly four months after Gunkel passed away. Skandor Akbar recalled meeting with Renesto and others at a hotel north of Atlanta one Sunday afternoon to plot out the new company and its strategy. “The territory was on fire,” he said. “I stayed there for three or four weeks. I can tell you right now she treated us very, very well.”

The new All-South Wrestling Alliance set the stage for a two-year “battle of Atlanta,” during which the promotions often ran competing cards in many Georgia cities. “From my perspective, it was the greatest thing that ever happened because it opened the door for me to get in the business,” said Simmons, who reffed for the group. “I tell people from November of ’72 until November ’74, when we went out of business, we had as much talent in this area as anybody has ever had anywhere in the country, probably more so … I’m working with all the top guys I’m used to, and on the other side, they’re flying in NWA people from all over the country trying to draw people.”

In September 1974, Ann announced her group had grossed more than $1 million in a year’s time, but it was running out of steam. The NWA poured money and talent into the old order, and changed to a management team that included wrestling impresario Jim Barnett and Cowboy Bill Watts. Ann ran her final Atlanta card that November and sold her business.

“Her hands were tied. She wasn’t able to get any new talent and her product essentially grew stale. She was really stuck,” said Tate, who has studied the schism as closely as anyone. “I admire her for going out and doing what she did. It was a very ballsy move and based on everything I’ve ever heard, she did the right thing in going out and saying, ‘I’ll show you.’ But I don’t think she realized how ‘good old boy’ the network was.”

* * *

Still, it’s fair to remember Ray and Ann, who died in 1987, as the trailblazers for a televised wrestling program that would catch fire within a few years. Less than two months before Gunkel died, WTCG upped its airing of Georgia Championship Wrestling to twice weekly. In 1976, the station went national, delivered the show across the country and ushering in the national cable-wrestling boom.

And Gunkel’s enshrinement in Waterloo has caused Pam to look even more closely at a father who died when she was just five. She’s found old pictures, even old booking records, that she never knew existed. Now working for an Illinois-based company, she never ceases to be amazed at how often the Gunkel name still crops up when people “Google” her dad.

“So I have found people come up to me, and say, ‘I found this picture of your dad that you’ve got to see.’ Or, ‘Oh, my, I didn’t know!'” she laughed. “It tugs at my heartstrings a great deal. It’s been very humbling and, at the same time, inspiring. I know he would be so proud.”

2008 TRAGOS/THESZ INDUCTEES

Roddy Piper

Abe Jacobs

Masa Saito

Leo Nomellini

Ray Gunkel

Stu Hart

TRAGOS/THESZ CLASS OF 2008 STORIES

- July 3, 2008: Melby Award winners deserving of honor

- June 28, 2008: Bret Hart’s speech from 2008 Tragos/Thesz Hall of Fame induction ceremony

- June 28, 2008: Piper, Saito, Jacobs enter Tragos/Thesz HOF

- June 27, 2008: Flood damage at Iowa HOF makes an impression

- June 27, 2008: How Ray Gunkel’s death changed wrestling

- June 20, 2008: Flood won’t stop Tragos/Thesz HOF ‘Super Weekend’

- June 14, 2008: Iowa wrestling museum flooded

- Tragos/Thesz Hall of Fame section in the Dan Gable Museum National Wrestling Hall of Fame