Charting the Territories is a unique, data-driven look at pro wrestling in the territorial era from award-winning historian and author Al Getz. The 1971-1973 Jim Crockett / Mid-Atlantic Wrestling Almanac offers a comprehensive look at the territory over a three-year period, with records for over 2,000 house shows. It also lists the full roster of wrestlers that worked for Crockett in the early ’70s, with statistics and charts showing exactly what their roles were. From the biggest stars and future Hall of Famers to the journeymen and up-and-comers working in prelims, they’re all here. The book also looks at changes both in the ring and behind the scenes, including two tragic deaths, the second of which would rock the territory to its very core and prompt the next generation of the Crockett wrestling empire to emerge.

The book is available at Amazon.com and Amazon.ca. Al Getz will also be at WrestleCade in Winston-Salem, NC from 11/29-12/1 with copies of all six Charting the Territories books.

SPOTLIGHT: LUTHER LINDSAY

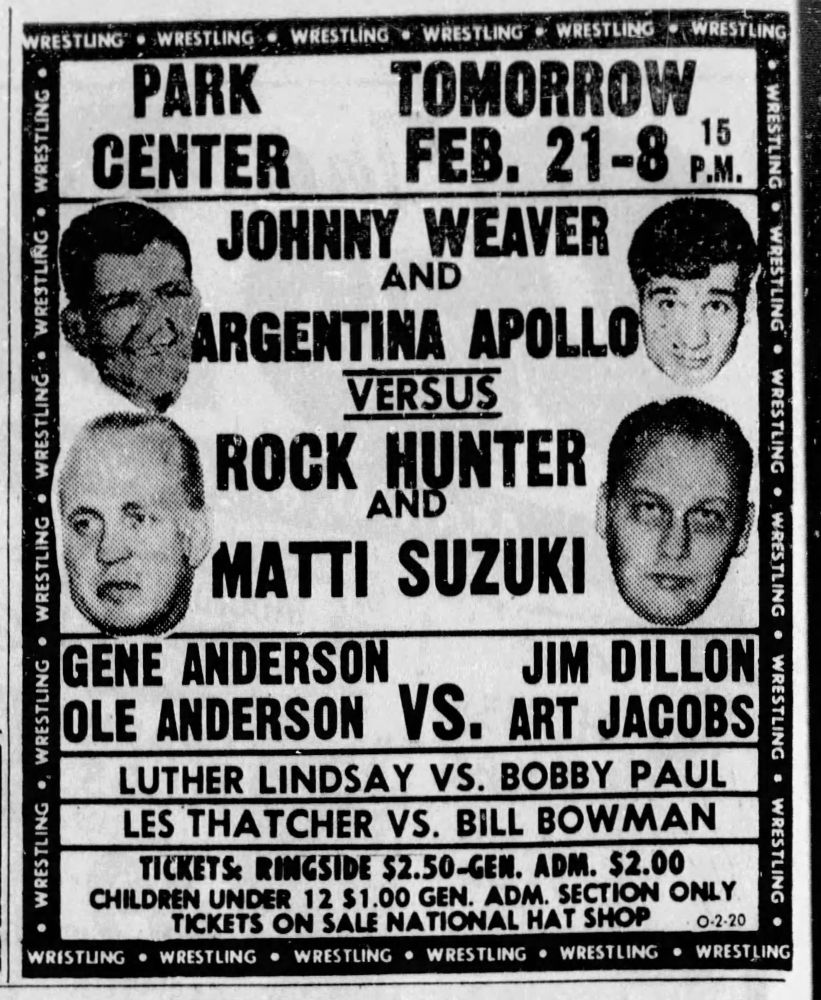

As Les Thatcher made his way back to the dressing room on February 21, 1972, having just defeated Bill Bowman, Luther Lindsay was heading towards the ring for his match against Bobby Paul. The two slapped hands, with Les saying, “Go get him, Buffy.” Luther replied, “I got it.”

Those were the last words exchanged between the two.

Luther Jacob Goodall was born on December 30, 1924, in Norfolk, VA. He served overseas as a corporal with the U.S. Army during World War II. After coming home, he played football at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) and was selected to the All-CIAA team as an offensive guard in 1948. While at Hampton, he met Gertrude Savannah Lindsay, a graduate of Dudley High School in Greensboro. The two wed in 1950. While Gertrude took Luther’s last name in marriage, Luther would later return the favor, taking her last name professionally and becoming Luther Lindsay in the ring.

In the 1950s, Luther Lindsay crossed paths with Stu Hart. It’s been said that Luther was one of the few men – perhaps the only – to make Stu tap out in the legendary “dungeon” in the Hart family basement. This earned a lifetime of respect from Stu. The seventh of Stu’s eight sons, Ross, was given the middle name Lindsay in honor of Luther (some of Ross’ earliest professional matches saw him use the ring name Ross Lindsay). According to his granddaughter Natalie (Natalya), Stu kept a picture of Luther in his wallet. He would also refer to Luther’s wife Gertrude as “Buffy.” Luther not only went along with it, but he started calling friends and fellow wrestlers “Buffy” as a sign of affection.

The card for Charlotte, NC, on February 21, 1972, which would be Luther Lindsay’s last match.

Les Thatcher eventually cut himself in on the joke, calling Luther Buffy, as he did on that fateful night in Charlotte. Their friendship was illustrative of the complex road Black wrestlers had to walk (or drive), even when they had the acceptance and support of their White peers. One winter night in 1968, Thatcher invited Luther to spend the night at his house. With a significant amount of snow on the ground, Les told Luther to stay with him instead of driving 100-plus miles home in dangerous conditions. Before dawn the next morning, Les heard Luther tooling around and found him packing his bags. Luther told him he wanted to make an early exit so that Les’ neighbors wouldn’t see a Black man leaving his home.

Pro wrestling often mirrors the real world, and its treatment of minorities in the mid-twentieth century was no different. By portraying himself as an athlete and not a gimmick, Luther maintained his personal integrity but perhaps floated under the radar, as he’s not oft mentioned in the same breath as men like Bobo Brazil and Bearcat Wright despite accolades that many consider to be on par. Author, journalist, and professional wrestling historian Ian Douglass (who penned Bahamian Rhapsody, which covers the history of pro wrestling in the Bahamas, as well as biographies on Brian Blair, Dan Severn, and Steve Keirn among others) had this to say about Lindsay:

By the time the 1970s rolled around, Luther Lindsay had more or less ascended to the position of being the most accomplished Black wrestler in the United States who didn’t rely on the assorted racial tropes that had been established in the prior generations of Black performers, and which still lingered in the presentations of many of his peers and emerging wrestlers. …

While Lindsay is often credited as a trailblazer in the South, his first foray into the region took place well after the tour pitting Don Kindred against Don Blackman first demonstrated how consistently Black wrestlers could draw large crowds in Southern states when pitted against one another. He also followed Jim Crockett’s original headlining Black duo of Don Blackman and Buddy Jackson in the spring of 1950.

Lindsay’s early time on the Pacific Coast was significant, inasmuch as he was permitted to act as a babyface foil to the two members of the dominant heel Brown Bombers tag team of Don Kindred and Frank James, both of whom were roughhousing headbutt specialists. Lindsay arrived in the region already labeled as the world’s colored wrestling champion, while supposedly seeking recognition from the National Wrestling Alliance for his championship. …

At the time of Lindsay’s death in February of 1972, he was something of an anachronism inasmuch as he was still clinging to world negro championship status in the post-Civil Rights era. Following his death, there would be very few instances of Black wrestlers claiming race-based titles, as the regular usage of such terms appeared to more or less die with Lindsay.

After almost two decades competing throughout the U.S. and Canada, Luther Lindsay returned from a tour of Japan in the summer of 1969 and made the decision to settle down. He and Gertrude stayed in Gibsonville, NC, on a little country farm not far from where she grew up, and he wrestled for Jim Crockett for the rest of his days.

During this time, Lindsay became occasional traveling companions with Jerry Brisco. Jerry may have had an ulterior motive for offering to drive, as he said that Luther made the best homemade wine in North Carolina, and one can assume that Luther shared his wine in exchange for the ride. Luther loved to ride in Jerry’s blue Mercedes with the top down. He also loved to listen to Aretha Franklin and B.B. King. But when Brisco would change the radio station to rock music, he said Luther was shocked at the colorful language (which was tame by today’s standards).

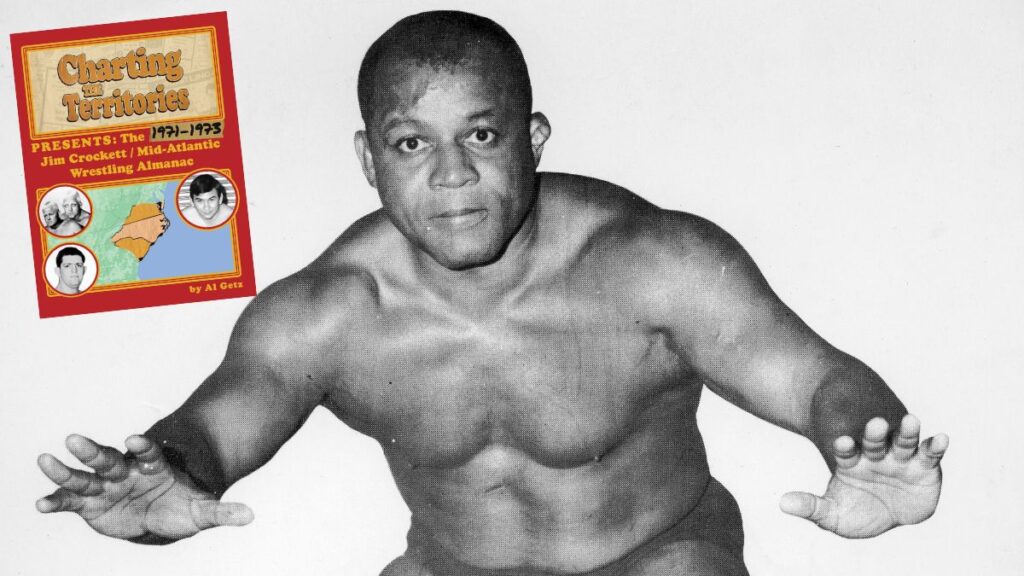

Luther Lindsay. Photo courtesy Chris Swisher

As he entered the back half of his forties, Luther was being moved down the cards slowly. While he was still booked in some main events, they were becoming fewer and farther between. On February 4, 1971, in Norfolk, Lindsay challenged Dory Funk Jr. for the National Wrestling Alliance World Heavyweight title. It was Lindsay’s last shot at the title, coming 17-1/2 years after his first, a match in Tacoma, WA, against Lou Thesz on July 31, 1953. According to currently available records, Lindsay was just the third Black man to challenge for the prestigious title since it had been formally established in 1948, following Seelie Samara and Bobo Brazil.

While Luther’s spot on the cards was trending downward, he was still well-respected by fans. Some say that Crockett wasn’t necessarily a fan of Luther, but he understood the value and credibility he brought to a wrestling card, particularly as the South was becoming more racially tolerant and crowds more diverse. As a result, Lindsay was “protected” by bookers. Upper mid-card babyfaces in Crockett’s territory had an overall Win Rate of 67.6% at this time. Lindsay’s was 81.2%. In fact, of the 94 wrestlers who worked for Crockett for at least three months between 1971 and 1973, the only one with a higher Win Rate than Luther was Thunderbolt Patterson.

Luther Lindsay won his match with Bobby Paul on February 21, 1972, in Charlotte. He pinned Paul in just 10 minutes with a “diving belly-flop,” a move he used frequently. After the referee counted the pin, Luther failed to get up (some reports say that he did get up but immediately collapsed). Police were called to the ring, and after Luther was given oxygen and CPR, a stretcher was brought in to carry him out of the ring. Les Thatcher and Johnny Weaver had gone to the ring initially, but as he was being brought to an ambulance, Les went back to the dressing room to get Luther’s bag, which he assumed he’d need at the hospital. As Les gathered his things, John Ringley came in and told him there was no need to hurry. Luther was gone.

The Charlotte newspaper reports on Luther Lindsay’s death in its February 22, 1972 edition.

Always the strong, silent type, Luther had kept some lingering health problems a secret from virtually everyone. In The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons, authors Steven Johnson and Greg Oliver wrote that he had showed signs of serious heart-related issues, but his wife was unable to get him to go to the doctor for further evaluation and, if necessary, treatment. Les Thatcher said he believed Lindsay had had walking pneumonia and didn’t allow himself to recover fully. Whatever the cause, the professional wrestling world lost a true professional that day.

RELATED LINKS

- July 11, 2024: Al Getz managed a complicated journey to Melby Award

- Jan. 7, 2024: What goes into my ‘Charting the Territories’ books

- Feb. 7, 2023: Passion, effort shines through in Charting the Territories

- SlamWrestling.net’s George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame story archive

- Tragos/Thesz Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame website

- Buy Charting the Territories Presents: The 1971-1973 Jim Crockett / Mid-Atlantic Wrestling Almanac at Amazon.com or Amazon.ca

- Buy autographed copies of Al’s books at www.chartingtheterritories.com

- Al Getz on X/Twitter

- Listen to the Charting the Territories podcast

- SlamWrestling Master Book List