Jon Langmead’s Ballyhoo!: The Roughhousers, Con Artists, and Wildmen Who Invented Professional Wrestling is out now from University of Missouri Press. He shares his experiences working on the book here.

Sometime a decade or so ago, when I was in my mid-thirties, I started wondering just why I’d been so interested in professional wrestling when I was a kid. Starting around 1984, when I was eight years old, I wasn’t just interested in pro wrestling, I was consumed by it. Like many kids of that era, I got caught up in the appeal of Hulk Hogan and the ubiquity of Vince McMahon’s World Wrestling Federation. The moment that really hooked me took place in the summer of 1985. I can remember seeing a short clip of Barry Windham and Mike Rotunda winning the WWF Tag Team titles from the Iron Sheik and Nikolai Volkoff on WWF’s weekly Saturday afternoon broadcast. Why this particular match so captured me, I can’t say, but I started carrying a Barry Windham baseball card around in my little boy wallet and dreaming of becoming a wrestler.

Still, I was aware even then that there was something fraudulent at the core of McMahon’s business. I knew this because I was above all things a dedicated reader of Stanley Weston’s Inside Wresting and Pro Wrestling Illustrated. The way some people have their universes expanded through Mad magazine or a sibling’s punk records, I got clues about life outside of the suburban development where I lived via Eddie Ellner and Craig Peters and Dan Shockett and Steve Farhood and the rest of Weston’s writers. To boot, living in Baltimore, we got exposed to wrestling broadcasts from around the United States. We could watch Mid-Atlantic Wrestling and the American Wrestling Association, sometimes even World Class Championship Wrestling from Texas, and seeing Ric Flair, Magnum T.A, the Von Erich brothers, the Road Warriors and so many other stars made it apparent just how superior these promotions were to whatever was coming at us from out of New York. Still, the WWF had its charms, and I was hardly immune to them.

Then, sometime around 1990, my interest ended just as suddenly as it had begun. Mid-Atlantic Wrestling had become World Championship Wrestling after its sale to Ted Turner, and the fancier the productions got the less I could relate to them. More importantly, I discovered music, and reading Rolling Stone and Spin soon took up whatever time I would have previously had for keeping up with the wrestlers who had kept me company all those years. By the time of the NWO and the Monday Night Wars in the late 1990s, I was so busy looking for the meaning of life in song lyrics and books that I never even noticed what was going on.

Which brings me back to 2013-ish. Hoping to better understand what had drawn me to wrestling in the first place, I started pouring through internet message boards looking for information on its history. I bought used copies of wrestling DVDs and caught up on the highlights of what I’d missed. I tracked down many of the writers who were responsible for the magazines that had so captivated me as a kid and wrote a long piece about them for PopMatters.

That got me connected to Greg Oliver and the group at Slam Wrestling. Greg, in turn, raised my awareness of a history way beyond anything I’d been previously aware of. Greg got me interested in the lives of the wrestlers and shared his vast collection of match records and biographical pieces. Through Greg, I also got connected to the community of wrestling historians who had dedicated their adult years to cataloging as much of the history as they could. I wrote in the Acknowledgment section of my about-to-be-released book Ballyhoo!: The Roughhousers, Con Artists, and Wildmen Who Invented Professional Wrestling that getting to know and talk with these guys was one of the great pleasures of my life and I absolutely mean it. I got to have beers with Mark Hewitt in Blythewood, South Carolina, and talk about rough and tumble fighting after spending the day looking through three boxes of papers belonging to the late promoter Billy Sandow. I got to have a beer with Howard Baum in Las Vegas and hear him describe his first impression of seeing the Magnificent Muraco. “It was like he had sunlight coming out of him,” he said. I remember writing that down on a bar napkin and stuffing it in my pocket so I wouldn’t forget it. I had the distinct pleasure of visiting Steve Yohe on a number of occasions at his house in Montebello and talking for hours. I dedicated the book to Steve, and I’m happy now to think of him as a true friend.

Ballyhoo!: The Roughhousers, Con Artists, and Wildmen Who Invented Professional Wrestling

I also got to talk with Don Luce, Koji Myamoto, Scott Teal, Tim Hornbaker, Steve Johnson, and many, many others. I got to email with the great sportswriter J Michael Kenyon in the weeks before he died. Apropos of nothing, he informed me that the expression is “champing at the bit,” not “chomping.” He also encouraged my interest in writing about the men who ran the business, who sat far away from the ring and the crowds. “Without the promoters,” he wrote, “where would we be?” That seemed significant and was a huge clue to me on how to eventually focus my work.

I knew that what I wanted to eventually write was a biography about professional wrestling. I’d always wondered how Nikolai Volkoff used to feel, for example, when a sold-out Madison Square Garden audience would boo and throw trash at him while he sang the Russian National Anthem before his matches. How did Kevin Sullivan possibly have the nerve to portray a pseudo-satanist in Florida back during the height of the Satanic Panic? What they were doing felt so much more method than the most method bit of acting you care to name. And on top of it all, it just felt insane. Wild. What a weird thing that it even exists. Where did it all come from and whose idea was it? Why did successive generations continue to find it all so engrossing?

The idea of basing the story around a person was suggested by a friend. Sitting in his back yard, he was helping me think through how I could structure it. It was his idea to look for a character whose life spanned the years I was interested in writing about; roughly the early 1900s through to the Columbus Trial of 1936, during which a group of promoters sued one of their wrestlers, Dick Shikat, for working off script. As soon as he had mentioned that idea, Jack Curley’s name popped into my head. Curley is a figure who looms large over early twentieth century wrestling. You can’t read about it without his name showing up. Still, while he wasn’t completely unknown, he was far from a household name. As soon as I had Curley in my head as the story’s guide rope, all the other pieces fell into place.

Jack Curley

Once I had the rough outline of a story in place, I spent a week spent digging through the archives of the University of Notre Dame’s Hesburgh Libraries, better known to wrestling historians as the Pfefer Collection. I covered my time there in a separate piece for SLAM, but it can’t be overstated just how instrumental the team there was to making sure I had every resource I needed throughout the entire process of writing and researching. Wrestling history all but comes to life right in front of you when you’re pouring through those boxes. The past doesn’t feel past at all when you’re holding a handwritten note from Boston promoter Paul Bowser or looking at the ledger for a night of wrestling at Madison Square Garden in 1932.

All along, I held out hope of finding some kind of skeleton key to the era; Jack Curley’s unpublished memoir, perhaps, or the last confessions of Gus Sonnenberg. I worked with dedicated librarians in archives around the world collecting clues and piecing together as much new information as I could. There was an awful lot I was able to find that I hope fills in some of the blanks that previously existed but sadly, if some Rosetta Stone-type work ever existed, I think it’s long been lost to the landfill. It’s heartbreaking to think of what we’ll never know. So little information was written down in the first place, and of that, so little saved. As Mark Hewitt told me more than once, all we can really do is make educated guesses about what was going on in these guys’ heads. The truth will simply never be available to us.

Jon Langmead with his book finally in his hand on December 14, 2023. Photo courtesy Jon Langmead

The era I cover is really the one in which all the basic tenets of professional wrestling were invented. While a Jim Londos match from 1930 would certainly move a lot differently than a Hulk Hogan match from 1985, I’m not sure the core appeal of watching the two men work is all that different. Same with the way Strangler Lewis knew just what buttons to push to infuriate an arena full of people in 1926. The Roddy Piper of 1986 never did it any better. Fashions may change, as the saying goes, but pro wrestling doesn’t. And I think there’s a story, too, about the growth of professional sports overall, and the kind of stranglehold they hold over our nation’s attention span. That growth was kicked off during the early years of the 1900s, and Jack Curley played a not-inconsequential role in it. If you want to keep going, I think there’s a story about belief in sports and sports heroes, and a story about cynicism and its corrosiveness.

It’s my sincerest hope that I’ve done the wrestlers and the promoters who made the era what it was some kind of justice. And not just them, but the work of all the historians whose work I leaned on: Greg, Mark, Steve (Yohe and Johnson), Don, J Michael, Tim, Phil Lions, Mike Chapman, Scott Teal, and many others. I say it in the book and I’ll say it again… Ballyhoo simply would not exist if it wasn’t for them. I hope the book tells the story in an engaging way and I hope that Toots Mondt, Jack Pfefer, Jack Curley, Jim Londos, Gus Sonnenberg, and everyone else I feature in the book feel a bit more alive and accessible and understandable than they did before.

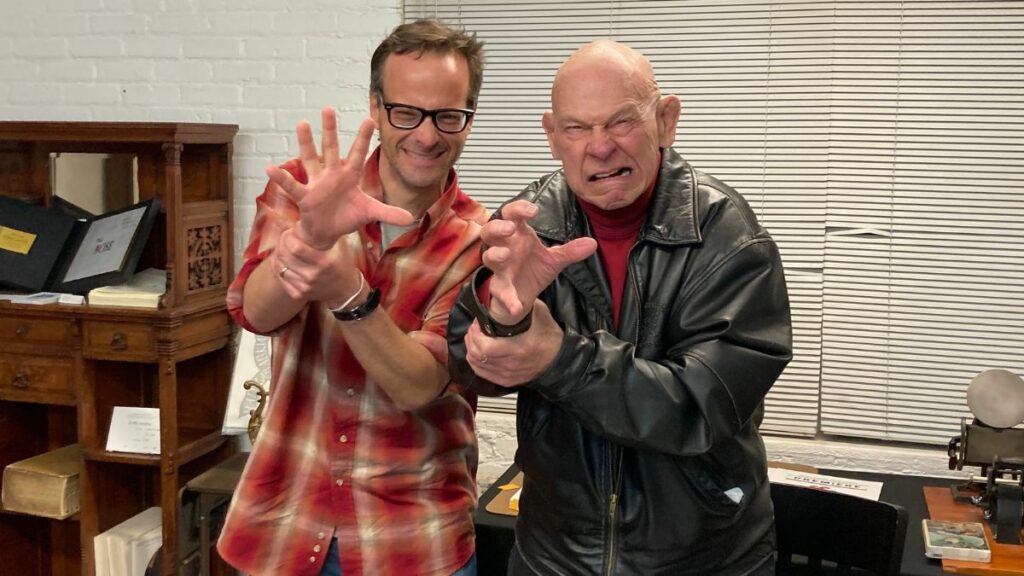

TOP PHOTO: Jon Langmead and Baron Von Raschke. Courtesy Jon Langmead

RELATED LINKS

- Review: Ballyhoo! centers on Jack Curley but tells a bigger, important tale

- Excerpt from Ballyhoo!: The Roughhousers, Con Artists, and Wildmen Who Invented Professional Wrestling

- Buy Ballyhoo!: The Roughhousers, Con Artists, and Wildmen Who Invented Professional Wrestling at Amazon.com or Amazon.ca

- SlamWrestling Master Book List

- All Jon Langmead’s SlamWrestling.net stories