Jack Adkisson was at a crossroads. He left college early despite his prowess as a discus thrower and football lineman. He tried but could not crack the roster of the most forlorn team in NFL history. He worked a stint as a firefighter and then got into wrestling, where people he admired foresaw a future for him. But he was scraping together pennies, and with one child and a second on the way, he didn’t know how long he could hang on.

So the rawboned 23-year-old turned to one of wrestling’s most eccentric characters, a Russian-Jewish immigrant who wore his lunch on his lapels and arose every morning with the intent of harassing the sport’s establishment in any manner possible. Pounding out a typewritten letter on March 17, 1953, Adkisson referenced Texas promoters Ed McLemore and Maurice Beck as he implored the irrepressible Jack Pfefer to help him realize his ambition.

“Mr. Mac as well as Mr. Beck think you can do wonders, in fact they both tell me that you can do more for me than any other promoter in the country, and I would most certainly appreciate the opportunity of working for you,” Adkisson wrote.

As the wrestling community awaits the premiere of The Iron Claw, a motion picture depicting the sad fate of the Von Erich clan, the what-ifs resonate again as they have across the decades following the too-familiar deaths of five of the six sons of Adkisson, aka Fritz Von Erich.

What if the talented David received proper treatment for whatever malady killed him in Japan at 25? What if the heartthrob Kerry averted the motorcycle crash that cost him a foot and sent him into a downward spiral that ended with his death by suicide? What if the demanding Adkisson eased up on his boys so Mike and Chris, who died by suicide at 23 and 21, felt less pressure to live up to the family name?

But the biggest what-if of them all remains. What if none of it ever happened?

A peek into the mind of a young Jack Adkisson shows how close he was to abandoning wrestling and how the fabled Von Erich character was merely a chance gimmick from an outlaw promoter. Some of Adkisson’s correspondence is part of the Jack Pfefer Wrestling Collection at the Hesburgh Libraries at the University of Notre Dame. It depicts a respectful young man in search of a big break that nearly eluded him. And, if it had slipped away, the subsequent glory and tragedy of the Von Erichs would have played out very differently.

Jack Adkisson — the future Fritz Von Erich — second from left on the clarinet at Crozier Tech High School in Dallas. Ancestry.com

CHAMPIONSHIP HURLER

Jack Barton Adkisson was a natural athlete. He was born Aug. 16, 1929, in Jewett, Texas, then a railroad stop of about 500 halfway between Dallas and Houston, to Benjamin Rush Adkisson Jr., a food salesman, and his wife Coren.

Jack Adkisson in a 1947 high school photo. Courtesy Ancestry.com

He started making a name for himself at Crozier Tech High School in Dallas, where he was the tallest clarinetist in the band. On the football field, he was a 6-foot-3, 210-pound tackle, while spring sports saw him in track and field events, specializing in the discus and shot put. As a junior, he placed third in the shot put in the prep division of the prestigious Southwestern Recreation Track and Field meet, following up as a senior with a second-place discus finish in the Dallas city championships.

Freshmen were ineligible for varsity football in 1948, so when Adkisson stayed in Dallas to attend Southern Methodist University, he spent a season on the frosh team. The following March, he built on his showing in the Southwestern Recreation Track and Field meet, winning the collegiate division discus at 134 feet, 4 inches and placing second in the shot put.

An ankle injury slowed Adkisson in the fall of 1949 when he played as a reserve lineman for Coach Matty Bell’s football Mustangs and won his only football letter. The highlight was a late-season start in a thrilling 27-20 loss to undefeated Notre Dame before 75,000-plus at the Cotton Bowl, where Adkisson helped block for All-American running back Doak Walker.

Adkisson always was a much better thrower than a football player, though, and Fort Worth sportswriter Dick Moore acclaimed him as “one of the Southwest’s better weight men.” In the spring of 1950, he scored first in the discus in the Bobcat Relays and the collegiate division of the Southwestern Recreation Track and Field meet. In May, he came within a foot of breaking a 10-year-old Southwest Conference discus record with a throw of 162 feet, 2 1/2 inches, and claimed second in the conference meet.

And that was the end of Jack Adkisson’s track and field days.

BOUNCING AROUND

On June 7, 1950, previewing the upcoming SMU football campaign, the Dallas Morning News found Adkisson working a summer job handling freight in a truck line terminal. Two weeks later, Adkisson, 20, married Doris Juanita Smith, a 17-year-old Louisiana native. They’d known each other for less than two months.

Jack Adkisson at SMU in 1950. Courtesy Ancestry.com

The newlyweds left Dallas for Corpus Christi, where Adkisson’s parents had relocated — his dad was working as a used car proprietor. Adkisson enrolled at the University of Corpus Christi (now Texas A&M-Corpus Christi) and coach Will Walls, who barely had enough players to field a team, thrilled at the addition of a big-time transfer from SMU.

The thrill wore off quickly. An ankle injury bothered Adkisson during fall drills. In October, he was called away from school because his grandmother was seriously ill. On October 20, the Corpus Christi Caller disclosed that Adkisson had dropped out of school. Records are incomplete, but it appears he played at most parts of two games for the Tarpons, who hobbled to a 4-6 mark.

Out of school and looking for work, Adkisson landed a job with the Corpus Christi Fire Department in late March 1951, earning $235 a month during a six-month probationary period and filling a gap caused by first responders called to the Korean War. Later that year, an off-duty Adkisson gained kudos for helping to thwart a gang attack on a local woman.

In June 1952, he changed gears again, giving pro football a stab, though he’d been off the gridiron for nearly two years. He inked a contract with the Dallas Texans, who represented the remains of the NFL’s New York Yanks, a team that dissolved after a miserable 1-9-2 season in 1951. Investors in Dallas wanted to turn the Texans into the Lone Star State’s first major pro football team and started scouting for local talent.

It’s likely that Adkisson, then up to 240 pounds, came on board through Texans ends coach Walls, his head coach in Corpus Christi. But on Aug. 7, with his wife due to give birth in six weeks, Adkisson quit the Texans, saying he had no chance to make the team.

It was quite an admission since the Texans were a talent flop, couldn’t pay their players, and moved to Hershey, Pennsylvania, and Akron, Ohio, to finish their 1-11 season. “Practicing with the Texans, we either played volleyball or just sat under a tree telling stories,” recalled Gino Marchetti, an original Texan and eventual NFL Hall of Famer.

Adkisson was going to tell stories, too, just in a different way. Less than three weeks after he hung up his football gear, he was in the ring as a professional wrestler.

LEARNING THE TRADE

Ed McLemore needed bodies. “Mr. Mac” promoted wrestling in Dallas under the auspices of Morris Sigel of Houston and the Texas Wrestling Agency, which owned two-thirds of the city grappling office.

In late 1952, McLemore split from Sigel, the Texas agency, and the National Wrestling Alliance, the cartel that controlled territorial wrestling, over disputes about TV payoffs and title swaps. Sigel’s group continued to run Dallas with brand-name talent, while McLemore, who held valuable TV contracts, cast about for new performers to stock his depleted shows.

Enter Jack Adkisson. Adkisson debuted as a wrestler in August 1952 and worked five matches that year, including a victory in Corpus Christi against Bill Sledge, where he was described as “a local fireman.” The Adkissons moved to Dallas, where Jack Jr. was born Sept. 21, 1952, and the young dad wrestled in preliminary matches for McLemore and Maurice Beck, who ran weekly shows at the Sportatorium.

Adkisson was a perfect fit as a good guy, a local high-school hero and former SMU player whose background could be slightly exaggerated as Doak Walker’s lead blocker. After working through a bad shoulder injury sustained in training, he was on the mat once or twice a week starting in January 1953, beating the likes of Joe Marlowe and Sammy Baldwin, and losing to Ricki Starr and “Tex” McKenzie. On the side, Adkisson earned a few extra bucks helping McLemore with his bookkeeping while learning the insides of the sport.

It wasn’t much of a living, though. With only a dozen matches under his belt by March 1953, Adkisson asked “Nature Boy” Tommy Phelps, a flashy future evangelist who wrestled for McLemore under Pfefer’s direction, to get him into the quirky manager’s camp. No response.

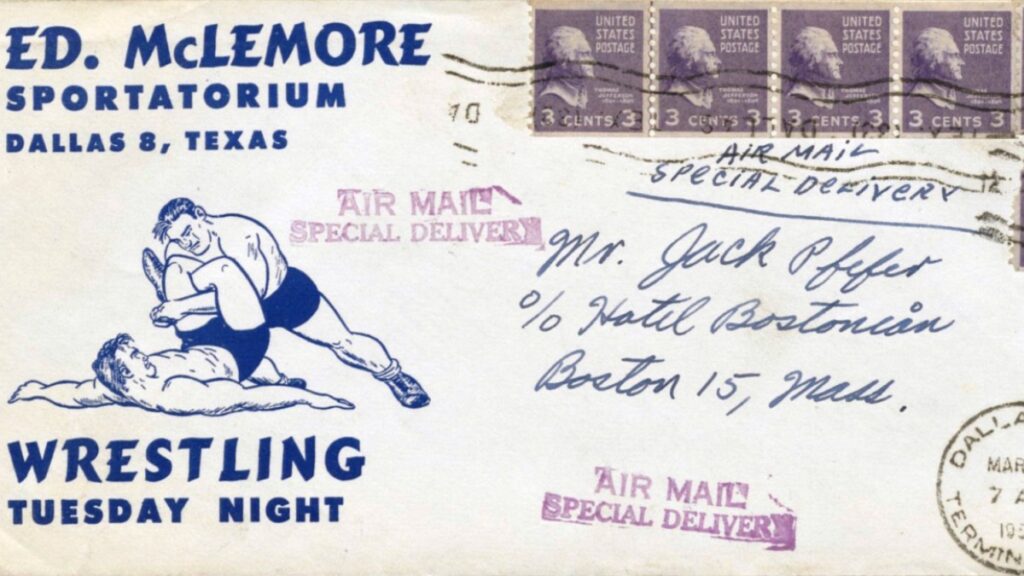

On March 17, Adkisson followed up with a special delivery letter to Pfefer, coating the envelope with nine 3-cent stamps and outlining his qualifications with a bit of hyperbole. He had been working with McLemore “for some time now” — a couple of months, actually — and claimed to have played a year of pro football for the New York Yanks. There is no record of him playing in New York, and his training camp experience with the successor team in Dallas lasted only two months.

“I have worked out with Nature Boy several times and he tells me that I have got what it takes to make a good worker if given the chance,” Adkisson wrote. “I have now had quite a few matches and am definitely determined to stay in the wrestling profession.”

Pfefer’s reply was quick and to the point. There was no room in his ensemble. Only slightly deterred, Adkisson appealed once more. On March 27, he wrote that he hoped Pfefer would keep him in mind even if he couldn’t use him at the moment.

“I would like to repeat that I am very anxious to come with you for the simple reason that Mr. McLemore, whose judgment I trust completely, says that I can learn more under you in a year than I would learn five years anywhere else in the country,” he said. “P.S. I had a match with Tommy last night, and I must say he is one of the best that I have ever worked with.”

Adkisson continued to work in Dallas and nearby Fort Worth, with occasional bouts in Corpus Christi, where he visited his parents, and San Antonio, where Bob Kline was running opposition to an established NWA promotion. Still, records show he had only about 26 matches in his first 11 months as a pro. The enjoyment was there. The money was not.

NEW PERSONA

Pfefer tossed Adkisson a life preserver in June 1953. Tony Santos was promoting in New England against the well-established office run for three decades by Paul Bowser. Pfefer worked closely with the independent-minded Santos, who agreed to give a shot to an unproven southerner in a northern city.

Adkisson’s SMU football ties meant nothing in Santos strongholds such as Hull, Massachusetts, and Nashua, New Hampshire. So Santos concocted a new identity and a new in-ring attitude for the big, blond-haired Adkisson.

“I have been working as Fritz Von Eric, the German Giant from Munich, Germany,” Adkisson wrote McLemore on stationery from a Boston hotel. “Santos has put me over continuously with the exception of a couple of disqualifications. All but two or three matches have been main events.”

It’s unclear how Santos or Pfefer settled on the Von Erich name. Adkisson told a reporter years later that it came from his mother’s side of the family, but there are no Von Erichs in the family tree of Coren Vessie Newberry Adkisson.

More to the point, Adkisson found that being bad was good business. Against challengers such as Tommy Griffin and Chief Little Bear, he relished playing a villain instead of a local, good-guy football celeb.

“It seems I have gone over exceptionally well with the crowds as a heel, and once or twice I have had to literally fight my way to the dressing rooms.” One night in Revere, Massachusetts, Von Erich reported the crowd practically trampled Santos as he tried to keep baying fans from attacking his new heavy. “That was one night my heart was in my throat. I couldn’t have felt more helpless in a cage of wildcats,” Adkisson said.

Though he was new to the business, Adkisson felt strongly, though mistakenly, that the success of independent and opposition promotions would sound the death knell for the five-year-old NWA. Santos had the northeast locked up, he declared.

“From all indications Bowser doesn’t stand a chance up here any longer. … It seems to me that it is no longer a possibility but a probability that the alliance will lose control before too long. Just a few more breaks, I believe, will do the trick.” Von Erich’s thinking was wishful; the NWA remained the lead combine of wrestling and he pushed his son Kerry to its world title in 1984.

GETTING BY

Once again, the enjoyment was there. The money was not. As part of Adkisson’s four-month run, Santos sent him to Montreal where he starred in 2-on-1 and 3-on-1 handicap matches for the first time. But even in his best month, Adkisson earned only an average of $142 a week. In a letter to McLemore, he was frank. He needed more and wrestling was not giving it to him.

“I am not saving anything to speak of, and if a guy can’t save some money in this business, what’s the use in staying? I have got to put away some money [emphasis his], if for no other reason than to pay for another baby that is due in Feb. ’54. Not only that but you can never tell when you are likely to get hurt and be unable to earn a living at all.”

Adkisson’s reference to a child expected in early 1954 is an unknown matter and not addressed in other writings in the Notre Dame collection. His second oldest and lone surviving son, Kevin Ross Adkisson, was born in May 1957.

In any event, Adkisson felt squeezed. As he put it, “Santos is paying me as well as anyone up here. I will have to admit that, but with the conditions as they are, it just isn’t enough for me to get by on and still put some away.” With some hesitancy, he sought McLemore’s permission to contact rival NWA promoter Morris Sigel in Houston for a return to Texas. “I plan to come home, if possible, for a couple of weeks before going anywhere else, after I leave up here. Can you use me while I am there?” he asked “Mr. Mac.”

FIRMER FOOTING

McLemore’s answer is not recorded, but it was an apparent yes. Adkisson started showing up for Sigel’s Houston office in November 1953 with stars such as Bull Curry and Duke Keomuka, who employed a body claw hold that morphed into Von Erich’s dreaded iron claw by 1959.

Under pressure from the NWA, Sigel and McLemore signed a revenue-sharing pact that ended the war in Dallas and opened up more opportunities for wrestlers. Adkisson started his second out-of-state tour in Minneapolis in the late spring of 1954, his first extended showing as the ruthless Fritz Von Erich.

Though he’d be known for his claw hold later in his career, Von Erich’s initial weapon of choice was a flying knee drop from the top rope, often on the back of an opponent. It generally resulted in a victory or a disqualification, but the difference was inconsequential at the box office. He worked for the last time as Adkisson in late 1954 in Texas, and then he was off to fame in wrestling hotbeds like Calgary, Buffalo, Toronto, and St. Louis.

“He just didn’t do all the goose-stepping and the ridiculous arm-waving. He just polished his image by not doing some things like that. He was Fritz von Erich, the German-type guy right after World War II. That went over big in other parts of the country,” said legendary Texas announcer Bill Mercer, who worked with him for years.

Adkisson got his first taste of wrestling ownership when he joined Dick Beyer, Billy “Red” Lyons, and Ilio DiPaolo in buying the Rochester, New York, territory from Pedro Martinez and pumping it up before the wrestlers went elsewhere.

He joined McLemore’s Southwest Sports as a partner in 1966 and acquired the promotion that would make his boys famous when his mentor died in 1969 at 63. “Ed went with me to Houston for my first match,” Von Erich said. “He’s been like a member of the family to me since he helped me get started.”

Fritz Von Erich and Eric Von Schrober in London, Ontario, in 1956. Terry Dart Collection

BLAME GAME

The residents of Sunny Acres Trailer Court in Niagara, New York, were beside themselves. Six-year-old Jack Adkisson Jr. was missing. Jackie had gone to play with a neighbor but had not been seen in 90 minutes. Shortly before 7:30 p.m. on March 7, 1959, one of the members of a search party found the child face down in a water-filled ditch that ran between rows of trailers. He had made contact with a live electrical line; a coroner ruled that the death was due to drowning while unconscious from electric shock.

The family tragedies mounted even as Fritz Von Erich’s World Class Championship Wrestling became the hottest property in the sport. The stories of David, Mike, Kerry, and Chris are as well-known as they are heartbreaking. “He was not easy or pleasant to work for. In a world of egos — he was definitely king,” the late NWA champion Lou Thesz said of Von Erich. “I know we should speak well of the dead, but I cannot think of one pleasant or positive thing to say about him. … When I think of how he destroyed his children, I find it terribly sad.”

On the other hand, Gary Hart, his booker for years, gave Von Erich a pass on charges that he manipulated his sons in ways that led to their untimely fates. “At no time did he ever look over my shoulder or second guess me; as long as business stayed good, he stayed away. So no, Fritz was not the one that really pushed the kids. He was happy that they were,” Hart said.

The suggestion that he was culpable in his son’s deaths rankled Von Erich until the day he died in 1997. “Everybody likes recognition,” he told the New York Daily News four years before his death. “They saw me getting a lot of it. They idolized me. I trained, was on television, a big name, why wouldn’t they want the same thing?”

The what-ifs are certain to live on after The Iron Claw concludes its theatrical run; the movie might well produce more second-guessing about the tribulations of wrestling’s most star-crossed family. It will remain speculation, of course. The Von Erich story is a tragedy and no one can accurately say what would have happened absent the accidents, painkillers, infections, drugs and depression.

But it is possible to say that without the fortuity that kept Jack Adkisson in wrestling 70 years ago, the Von Erich story would be different, if it was one at all.

“A radio station called me right after the 9/11 tragedy when the towers went down, like I’m an expert on grief,” Kevin Von Erich told SlamWrestling.net a few years ago. “And they said, ‘How do you deal with it? How do you get over it?’ I hate to bum everybody out, but the fact is grief doesn’t ever get any better.”

— with files from Greg Oliver. Thanks to Gregory Bond and James Cachey at the Hesburgh Libraries at Notre Dame.

RELATED LINK