Competing in two Olympic Games is a special feat, and Toronto’s Dan McDonald did just that, fighting on the mat in 1928 in Amsterdam and 1932 in Los Angeles. Yet the silver medalist from the ’32 Games never comes up when we talk about amateur stars who turned pro.

It’s time to change that discussion.

* * *

McDonald was born on October 9, 1909, in Toronto and was an athletic kid. At age 17, he found a home at the West End YMCA in Toronto, at the corner of College Street and Dovercourt Road. There, he started to learn the sport that would bring him much success.

Records are scarce for the time, and The Great Depression no doubt factored into the number of meets McDonald competed at, but according to the de facto book on amateur wrestling in Canada, Glynn A. Leyshon’s Of Mats and Men, McDonald never lost a bout in the country.

* * *

Danny McDonald on the 1928 Canadian Olympic team.

The 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam were perhaps a little ahead of where the 19-year-old McDonald was at the time, but the experience helped shape him — and the names he met!

The Canadian wrestling team won three medals: Donald Stockton took silver in the freestyle middleweight discipline; James Trifunov (freestyle bantamweight) and Maurice Letchford (freestyle welterweight), each with a bronze; Toronto wrestler “Lefty” Priestly was a friend of McDonald’s and on the team as well. There were some otherworldly Canadians at the Games, too, including legendary sprinter Percy Williams, taking gold in the 100m and 200m sprints, and the incomparable Bobbie Rosenfeld, perhaps the greatest female Canadian athlete ever, with a gold medal as a part of the 4×100 women’s relay, with a silver in the 100m race to boot. Another Canadian wrestler, who didn’t medal, would end up as one of the greatest U.S. collegiate wrestlers ever and a successful, globetrotting pro wrestler — Earl McCready.

According to Of Mats and Men, McDonald wasn’t an automatic choice for the Games:

The 134 lb. class was comparatively easy for Dan McDonald of Ontario, who got two straight falls over Stewart in less than three minutes, but the ease with which he won did not impress the members of the Selection Committee and he was not selected (for the Olympics) at the time, but the Committee recommended both he and Priestley for consideration by the Olympic Committee, and McDonald was later selected to go on the wrestling team in place of one of the boxing classes which was eliminated.

Complicating it was that when they held the Olympic trials in May 1928 at the West End “Y,” McDonald was injured and so didn’t participate.

In Amsterdam, McDonald won one bout, beating Great Britain’s Harold Angus, and lost a second to eventual bronze medalist Hans Minder of Switzerland. Chalk it up to a learning experience for a young man still growing. He’d gone from winning a gold medal at the Ontario Championships at 115 pounds to 134 pounds at the ’28 Games.

The Toronto Star reported on the return of the wrestlers to town in its August 17 edition:

The advance guard of the Olympic athletes arrived in Toronto yesterday. One was Jim Trifunov of Regina, an employee of the Regina Leader, who competed in the 123-pound bantam wrestling class, worked himself through the preliminary contests and eventually secured third prize.

The other early arrival was Dan McDonald of Toronto, another wrestler who competed in the 134-pound class.

Trifunov referred to the different style of wrestling at the Olympic games compared with the method employed in Canada. “It was difficult,” he said. “to accustom oneself to their style after having practised another for a number of years, and that had a great deal to with our contestants not doing as well as it was expected they would do.

“We had a splendid time in Holland,” added the Regina man. “The Canadian committee did everything they possibly could for our comfort and enjoyment, and the co-operation between the officials and competitors was remarkable.”

* * *

There was no real living to be made as an amateur wrestler between Olympics, but one still needed to stay in shape. McDonald appears often on various shows held by the Parkdale Canoe Club or Toronto Canoe Club. These meets were advertised and often also featured boxing, so someone was making a buck to put on the events. What trickled down to the competitors?

And make no mistake, McDonald was a competitor — and not just in wrestling.

In the July 3, 1929, edition of the Toronto Daily Star, the famed columnist Lou E. Marsh hyped a rowing race with McDonald on it at the Toronto Canoe club:

“The boys from the foot of Dowling Ave. claim that they have a real comer in Danny McDonald in the singles event. McDonald is an athlete in ever sense of the word. He represented Canada in wrestling at the Olympics last year, wrestling at 135 pounds. Danny has been paddling around the T.C.C. for the last four or five years but up to Dominion Day ha not entered a race and he is therefore still eligible for the junior singles. At the Dominion Day regatta he entered the senior singles in order to gain experience and paddled a long stroke down the course to finish second to Roy Nurse from Balmy Beach, and to lead a field of strong contenders. With a few more weeks of experience, Danny should make them all step at the C.C.A. finals.”

Amateur wrestling meets would draw fans too. On November 1, 1929, McDonald fought at the Ravina Rink in Toronto’s west end, on a card put together by the West Toronto Athletic Club. The Globe reported on McDonald’s bout:

In the final wrestling bout Larry Labelle caught a tartar in Danny McDonald, the Dominion lightweight champion. McDonald proved to be just as good as his reputation, and, although smashed down twice with heavy body slams, his cleverness soon gave him a chance to pin Labelle’s shoulders for a fall in 5 1/2 minutes. When they came back for the second round McDonald tried hard to duplicate the fall, but Labelle weathered out the ten minutes. This bout was the feature of the evening and had the crowd in a state of excitement throughout.

* * *

The Oshawa Daily Times seemingly fell in love with McDonald in a series of articles leading up to a card east of Toronto. “Danny is a treat to watch, as he is a perfect wrestler. Danny is also an outstanding paddler, having won many championships in that sport,” reads an unbylined story on January 2, 1932.

The newspaper tied McDonald into Cliff Chilcott, the physical director at Oshawa Collegiate and Vocational Institute, calling McDonald a protégé and, therefore, their battle on January 13 was an epic student-teacher match-up. It was noted that McDonald was a daredevil for riding a motorcycle — but the story helps one grasp why there aren’t a slew of amateur results for McDonald in 1930 and 1931:

Chilcott is in mortal dread that Danny and his motorcycle will try to climb a tree, remembering that it was just before the British Empire Games last year that Danny broke his leg in some such adventure, losing him the opportunity to take the measure of the best mat men the empire had to offer. Danny is a ‘natural’ and has fulfilled every promise as a wrestler he showed from the first day he strolled into a gymnasium and learned about wrestling. he is a great fellow, too. A hard man to meet in the ring, but a lovable character just the same. Last year he went hunting near Sudbury. He saw a deer in the water. It was easy matter to shoot it there, and just as easy to pit it by letting it get to the shore, before it got into the bush. Discarding both alternatives which seemed to him to be unsporting, he cast aside his rifle and jumped into the water, and armed only with a hunting knife gave the deer a man to man chance to get away. The deer didn’t get away which was the only sad part of a yarn which is vouched for.

If it was a pro match instead of an amateur, one might have questioned one of McDonald’s greatest supporters and advocates in the paper, Lou Marsh of the Star, as the referee. The Daily Times‘ recap: “The bout was the fieriest and fastest on the card, and both men gave a fine exhibition of close wrestling. Almost all of a wrestler’s repertoire was exhibited in this bout, and the way the students cheered their instructor when he made a particularly clever move spoke much for his popularity in the school. The match was also a draw, as neither wrestler was able to establish the margin of victory. Lou Marsh acted as referee for the bout.”

* * *

When the 1932 Olympics came along, McDonald had grown to 158 pounds and was in the welterweight class. There were no big expectations on the six-man wrestling team in Los Angeles, the way there had been in Amsterdam. Lou Marsh summed it up on August 5: “As was anticipated, Danny McDonald, the Toronto Canoe Club paddler, was the only one of the Canadian wrestling team to make any sort of a real showing.” McDonald was the only Canadian grappler to win a bout, eventually taking five, enough to claim the silver medal. (Marsh was in L.A. for the Games, and language such as this is part of the reason his name has been taken off the Lou Marsh Award for the top athlete of the year in Canada. McDonald had little trouble beating Yoshio Kono of Japan. Marsh’s reporting: “The Jap might know all the jujitsu in the book, but Dan didn’t give him a chance to open the first page.”)

Of Mats and Men explained McDonald’s run to silver:

McDonald pinned Kohno (Japan) in four minutes and 12 sec. With a bar nelson and leg ride. In the second round. he beat J. Zarnbri (Hungary), lost to J. Von Bobber (USA) pinned Z. Folkak (Germany) and decisioned E Leino (Finland). The loss to Von Bobber was particularly bitter. In the final classification, the black mark system was used. Von Bobber had three while McDonald had four because while McDonald had two falls and two decisions and one loss, Von Bobber had only one fall and four decisions. In those days a fall counted no more than a decision. A short time after this falls were given a higher status — but it was too late for Dan McDonald.

* * *

McDonald was feted at his home “Y” on Tuesday, October 11, along with others who had succeeded through their access to the facility: boxer Horace “Lefty” Gwynne, diver Alfie Phillips, and race walker Hank Cleman.

* * *

As 1948 Olympian Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon often said, you can’t eat your medals, though, and McDonald wasted little time turning professional.

“Danny McDonald, stellar wrestler, who represented Canada at the last Olympic Games, and was runner-up in the 160-pound division, has turned professional. His first match was in Kitchener last Monday night,” wrote M.J. Rodden in The Globe, presumably referring to December 5, 1932. “McDonald is putting on weight, and it is expected that he will soon be a light-heavyweight.”

McDonald, weighing 165 pounds, had his first pro bout in Toronto, on a card promoted by the Shamrock Athletic Club, at Arena Gardens on March 16, 1933, in the opening match of a card headlined by Sandor Szabo beating “Hangman” Howard Cantowine in two of three falls. He drew with Frank Malcewicz (brother of future San Francisco promoter Joe Malcewicz), and The Globe noted that he “convinced all present that he could hold his own with most at his weight in professional ranks.” (Also on the show was McDonald’s fellow Canadian Olympic wrestler from ’28, McCready, who drew with Jim Clintstock when the 10 o’clock curfew arrived.)

Unlike McCready, who went from the 1928 Olympics to compete for Oklahoma A & M, becoming the first-ever winner of three-straight NCAA wrestling championships, McDonald decided to get a “real” job (besides being a pro wrestler). He spent two years as the wrestling coach at the Ontario Agricultural College in Guelph.

McDonald’s influence was over more than just collegians. In a May 1933 column, M.J. Rodden, The Globe‘s sports editor, credited McDonald and Walter Parnell, among others, for boosting interest among Toronto youth in amateur wrestling, on the eve of the Ontario amateur championship. Maybe they were inspired by newspapers like the Windsor Star, which called McDonald “somewhat of an expert at the finer arts of mat torture”?

* * *

(Note, it can get a bit confusing with the whole Dan McDonald name. There was a middleweight pro wrestler from Sydney, N.S., who predated the Olympian a little bit. Dano McDonald was actually Jim “Dano” McDonald from Hamilton, Ontario, and he died in 2004.)

* * *

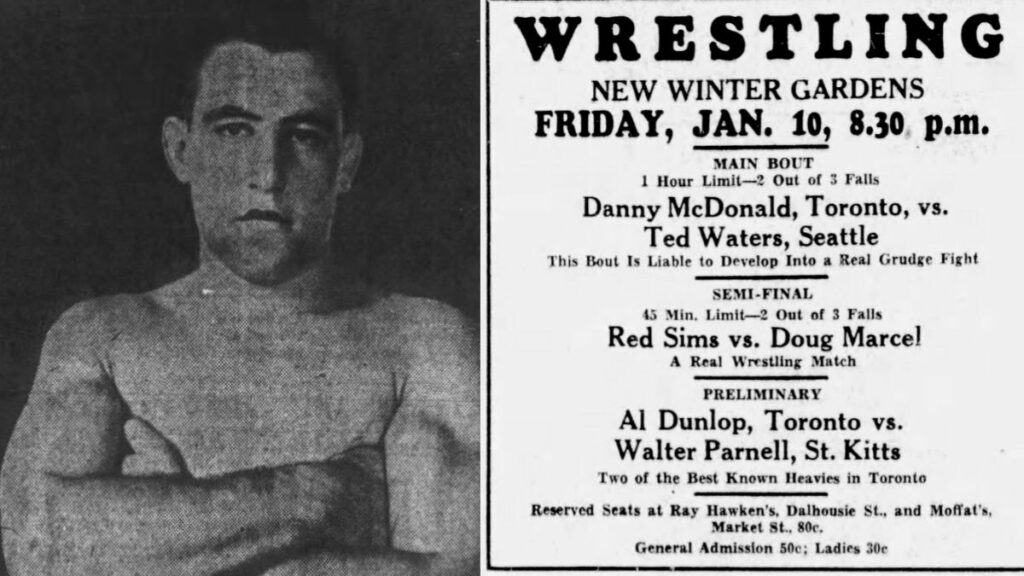

McDonald on a bout in Akron, Ohio, on March 18, 1935.

In hyping a match against Young Angelo at Toronto’s Mutual Street Arena in March 1934, the Toronto Star noted that McDonald was the city’s “logical contender for Gus Kallio’s middleweight world title.” Then, in the bout “Danny Boy” and “his lightning fast legs supplied the wrestling” won the bout. (A great last line to the uncredited story: “It was a good show, the right men won, the crowd was pleased and the roof leaked on the press table. Oh, the wrestlers were light heavies.”)

Wrestlers did their best to keep in touch with the sportswriters back home, and McDonald was no exception, dropping a note to W.T. Munns, for his On The Highways of Sport column in The Globe, that, in November 1934, he was out in British Columbia, winning a bout in Victoria.

Most of McDonald’s matches, though, appear to be within reasonable driving distance of Toronto, through the province of Ontario, and into neighboring states Michigan, Ohio, and New York.

* * *

McDonald on a bout in Brantford, Ontario, on January 10, 1936.

On Saturday, August 31, 1935, McDonald married Ruth Downing, of Toronto, who was an accomplished athlete herself, a competitive swimmer. Danny’s old pal, Lou Marsh, in the Star, previewed their union on August 23:

Don’t worry about the chances of Pat Downing’s daughter Ruth in the women’s five-mile swim next Thursday. She takes a dip in the sea of matrimony next week and not in the turgid waters behind Exhibition park sea wall. Miss Downing’s entry is in but the hubby-to-be, Danny McDonald, the ex-British Empire wrestling champion, has exercised his rights in advance and said to Ruthie, “No swim this year, young lady.”

* * *

What is remarkable when detailing McDonald’s story is how it all drifts off around 1936, with very few mentions of him.

Apparently, he became a dairy farmer, and did that for the rest of his life, which ended on October 10, 1979. All that could be found to mark the occasion was a line in a Jim Proudfoot column in the Toronto Star: “Dan McDonald, who died at 72 this week, won a silver medal for Canada in welterweight freestyle wrestling at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles.”

He was recognized in his lifetime at least, as MacDonald was inducted into the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame in 1976 and the Canadian Wrestling Hall of Fame in 1978.