The next several months were hit and miss.

Sweet Daddy Siki, then a local disc jockey who lived one street over from my house in Parkdale, said no. He was writing a book. Billy Red Lyons was a polite no thank you. He felt there were too many stories that should not be told. Rejection fueled my curiosity.

Tony Parisi, a very personable man who looked like he could still wrestle, had a funny yarn about him and Dominic Denucci filling their car with stolen oranges before getting stuck. Maybe.

Tony Marino, fit and coarse, in a tie-dyed 1960s style shirt, with hairpiece and a jet black goatee carefully fringed with white streaks that hinted buyer beware, laughed through a very disturbing story about a cross-dressing prostitute and an anonymous rookie wrestler — Billy Red was right, some stories should not be told and weren’t.

Others who expressed interest: arch villains Kurt von Hess and Waldo von Erich (my two favourite German heels), “Beautiful” Bruce Swayze and The Canadian Wolfman Willie Farkus. Lou Thesz did not. I’d met them all after a WCW legends reunion in Buffalo at Tony Parisi’s hotel in Niagara Falls, Ontario. Thesz, whose contribution to wrestling I did not fully appreciate at the time, was interesting but humourless.

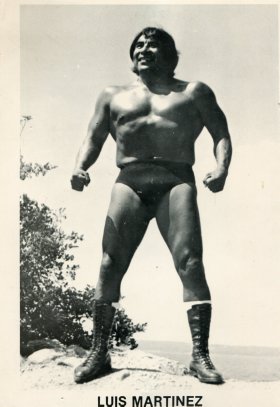

I found Luis “Arriba” Martinez in Columbus, Ohio — if his health returned, he’d be happy to do it.

Luis and I corresponded by snail mail. For a wrestler, his hand-writing was typical; it pointed to a formal education cut short, for reasons I never found out. But at least it was legible.

By comparison, the Dog’s handwriting was nearly impossible to read. It looked like he could barely hold a pen — his hands were gnarly and arthritic and I suspected broken fingers weren’t something you bothered to fix back in the day.

But like the Dog, Luis had few complaints; he was wistful more than anything, life had been good. He confessed to being “the greatest sinner” while on the road but was now deeply religious and committed to helping save the odd soul.

“Sometimes I wonder where all the money went,” he admitted. That struck me — he just wondered but didn’t seem to care. I sensed a calm presence between the lines, something I’d encounter again and again over the life of the project. Unfortunately, Luis became difficult to reach and we eventually lost touch.

Dick Garza was unintentionally funny. That he had to live his Mighty Igor gimmick in public was drop-dead funny in that it seemed only someone as innocent as Igor could be convinced that had to be done.

At only 19, Butcher Vachon started out as Zolotoff the Mad Russian.

Yet Butcher Vachon, who started out as a Russian heel, said promoter Harry Light insisted he eat raw onions so, presumably, he’d smell like a Russian heel when questioned about his accent.

Butcher laughed recounting this, but Garza didn’t.

At that time, wrestling was positioned as real with the belief being that if the public ever suspected it wasn’t, they wouldn’t buy a ticket for the show. Wrestlers had to guard the empty vault, they had to live the gimmick, heels travelled with heels, you couldn’t lose a bar fight; this was a tribe who’d vigorously defended their secrets long before I ever showed up, which explained why Garza was reluctant to get involved.

Hans Schmidt wouldn’t either, which was a real shame, because at the height of his popularity in the ’50s, the FBI paid him a visit at the Chicago wrestling office to ask about his political interests. Jim Barnett described the interrogation in detail. Was he really a Nazi? Was he associated with any extremist groups? Where did you buy the jack-boots?

I kept hearing similar stories: Waldo Von Erich getting tossed in a Pennsylvania jail for goose-stepping down main street in his Gestapo uniform, Lou Albano and Tony Altamore, a.k.a. The Sicilians, being told by the mob to ditch the black gloves — I became more and more curious. Who were these people? What did they go through? How different were they from their personae?

Johnny Valentine was 1950s cool and methodical over the phone and worked me like I was at ringside — wrestling was real for him, do not press the point. We also talked segregation and how he’d been the first white wrestler to have a mixed race match in Texas. Plus others said he was a gonzo prankster. Johnny wanted in.

Gene Kiniski, an inveterate swerve fiend and former NWA champ who never met a microphone he didn’t like, also wanted in.

Don Leo Jonathan, the slow-talking Mormon Giant, once a cast member in The Little Rascals, whose father, a wrestler named Brother Jonathan, made him leash and walk Cold Chills, their seven-foot rattlesnake, down Sunset Blvd. to get some publicity in Hollywood … when he was just five years old. That he had some good stuff on the Dog was almost a bonus. And Don Leo wanted in.

Don Leo vs. Kowalski, early 1970s Grand Prix. Photo by Tony Lanza

MAD DOG:Well, for me wrestling was an escape; I escaped from school, I used to hate school with a passion so I collected stamps. With stamps I could go to all countries of the world by looking — I was only good at one thing in school and that was geography, so I wanted to be a wrestler because when I became a wrestler I could travel all over the world and see all the countries, get away from school — just get away from it — and travel and see the world. And I did it and I loved it, and if I had to do it again I would do it tomorrow.

PAGE 1 | PAGE 2 | PAGE 3 | PAGE 4 | PAGE 5 | PAGE 6

Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon story archive

BONUS! A Christmas card from Luis Martinez: