EDITOR’S NOTE: This biography is courtesy the book, The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons, by Greg Oliver and Steven Johnson, with Mike Mooneyham.

* * *

Having dropped out of the University of Utah after his junior year, where he had tackled and kicked for the football team and served as a heavyweight on the Redskins wrestling squad, Wilbur Snyder found himself back in Van Nuys, California, driving a cement truck for his father’s business.

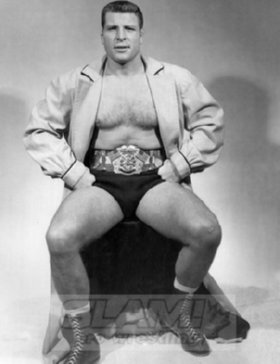

Champion Wilbur Snyder poses for a photo. Courtesy Chris Swisher.

Unable to be drafted and play pro ball until his college class graduated, Snyder, begged Benny Ginsberg to get him into wrestling. Ginsberg took him to meet Los Angeles booker Jules Strongbow, who promptly said, “We don’t need any more football players in wrestling.”

For a less determined man, this might have been the end of the story. Instead, Snyder latched on to Jerry Christy, nephew to L.A.’s famed Vic and Ted Christy, who had only debuted himself in 1951. “I refused many times,” recalled Christy of Snyder. Though both had gone to Van Nuys High School, they were too many grades apart to know each other. Eventually, Christy caved and began unteaching some of the lessons Ginsberg’s shared. “I got him and taught him the right things like he had a hard time when he was selling. He said, ‘I just can’t do that!’ … But he learned.” Christy convinced Don Sebastien, a small-town promoter in the shadow of Hugh Nichols in L.A., to watch them work out; Snyder’s debut at the Valley Garden Arena in early 1953 followed.

Having heard about the local product, the big-time promoter headed to the rinky-dink show. “Hugh Nichols saw him, and oh my God, Hugh Nichols just fell in love with him,” summed up Christy.

From there, Snyder shot into prominence very quickly, challenging top stars like Mr. Moto and, most surprisingly, NWA World champion Lou Thesz, in the summer of 1953, less than a year into his part-time career.

“The same Wilbur Snyder who couldn’t quite make the first team at the University of Utah football camp several years ago will be wrestling for the world’s championship in Salt Lake July 9,” teased Hack Miller in The Deseret News. “They’ve brought our Wilbur along pretty nicely in the mat business. He’s a big and handsome feller with a fine figure. He’s the handsome type — the best you could get for today’s TV market.”

It was almost as if someone were trying to convince Snyder to give up on the football dream, which he finally did after the 1953 season, but not without much notable effort.

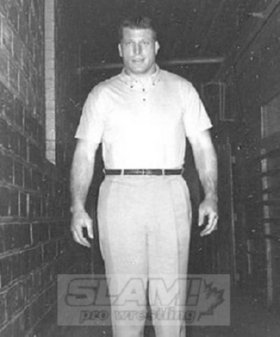

A young Wilbur Snyder early in his career, in London, Ontario. Photo by Terry Dart

Snyder, born September 15, 1929, in Santa Monica, was a football star and gymnast at Van Nuys High, marrying his sweetheart Shirlee Ann Hanson right after graduation at the Little Church of Sherman Oaks. At the University of Utah, Snyder, like many players at the time, he covered multiple positions on the gridiron. “Snyder weighs 210 and is canny at the catch,” read a 1949 report, which also praised his placekicking. In April 1950, he dropped out of school.

“It was simply a case of needing money,” Snyder said in a magazine profile years later. “I’d married Shirlee before my freshman year you see. So I went to work for my father in the trucking business. I also looked up Bob Waterfield, my old high school teammate and he got me a tryout with the Los Angeles Rams.” When the Rams didn’t bite at that 1952 training camp, he filled time working with his father until the Edmonton Eskimos of the Western Interprovincial Football Union called, and Snyder joined partway into the 1952 fall season and played the next as well.

Before the 1953 season started, Snyder took to the mats, including a bout in Edmonton. “A new star hove onto the horizon at the Sales Pavilion Tuesday, in the person of a fellow named Wilbur Snyder. And before Wilbur is here much longer, he will be the toast of Edmonton’s wrestling fraternity,” praised the Journal. Notably, teammate Joe Blanchard was on the same card, heading down the same dual-career road.

A close-up profile shot of Wilbur Snyder. Courtesy Chris Swisher.

Blanchard said they never discussed their wrestling plans and was not jealous of Snyder’s quick success. “He got an instant break. He was a big, handsome guy, a good athlete. He was a good worker and did a good job.” Gene Kiniski was a third tackle on those Eskimo teams that would turn pro wrestler.

The team tolerated the wrestling early in the season, but not when the playoffs approached, and rosters had to be set, including an eight-man American import quota. “There was no stipulation in our contracts that we quit on Oct. 1,” said Snyder in November 1953. “It was an unwritten gentlemen’s agreement.”

The six-foot, 2-1/2 inch Snyder threw his 230 pounds around in the ring much the same as he did on the field. “Wrestling helps you in football because there is no pre-season sweating into shape,” said Snyder. “By wrestling in the offseason, you’re always in shape and the mat game sharpens your reflexes for football. I also use much of my football training in the ring.”

After realizing there was far more money to be made in wrestling, Snyder told the team he was done in May 1954, and furthered his in-ring training with Warren Bockwinkel and Sandor Szabo — “They worked some of the rough edges off me” — and Tony Morelli in Hawaii.

“The guys around there, if you said, ‘Come work out with Wilbur,’ you worked out with him,” Blanchard said of the Los Angeles scene. “Thesz was around then; Thesz worked out with him some. Wilbur, he was really a good athlete.”

It took a while, but eventually “The California Comet” assumed the mantle of “The World’s Most Scientific Wrestler,” and the move he most popularized was the abdominal stretch. The Milwaukee Journal dubbed Snyder “a veritable arsenal of virtue — armed with everything that is right and proper — including a crew cut, suntan and shell-like ears.”

Nick Bockwinkel struggles in Wilbur Snyder’s abdominal stretch.

Snyder would also have a disciple in Nick Bockwinkel. “My dad did so much to train him that he was very kind and, of course, returned the favor and helped train me. So it wasn’t so much that he was my idol, but everybody said, ‘You almost look like Wilbur’s duplicate.’ I guess what I did was I mirrored him — his style and his movements, in the ring. I had a tendency to do that,” he told Whatever Happened To … Bockwinkel and Snyder would be an on-and-off team for a few years. Snyder would form other championship teams with Leo Nomellini, Dick the Bruiser, Moose Cholak, Luis Martinez, Pat O’Connor, Paul Christy, Pepper Gomez, Danny Hodge, Dominic Denucci, and Spike Huber.

If it wasn’t for the break of working with Thesz early, perhaps Snyder wouldn’t have made much of a name for himself. “We made a lot of money together,” remembered Thesz in the Wrestling Observer following Snyder’s death on Christmas Day 1991 in Pompano Beach, Florida, from heart failure while battling lymphatic leukemia. “He had the crew-cut and was a football player and he really had it. He had good reflexes and learned to be a good performer quickly. We ran the feud all over the country, usually stretching it to three meetings (in each city) and sold out in a lot of cities that usually didn’t do business.”

Wilbur Snyder had plenty of reasons to smile. Courtesy Chris Swisher

Aside from Thesz, Snyder’s early years are most intertwined with Verne Gagne, whom he knocked off for the U.S. title on April 7, 1956, at Chicago’s Marigold Arena, after Gagne’s five years as champ. Take their bout at Milwaukee Stadium in August 1956, with Jack Dempsey as the ref; it drew a record crowd of 16,069 for a gate of $33,689.90, bettering the previous attendance mark by almost 4,000 (Gagne versus Ric von Schacht in 1952).

In 1959, Snyder was a key cog in the attempts to get Detroit up and running again and there his career particularly started intertwining with Dick the Bruiser (Dick Afflis). Not only did they become great opponents, but they would become friends and business partners. In April 1965, the two started Championship Wrestling., Inc., with their wives as the figurehead directors of the corporation, and would promote around the Indianapolis area for decades under the World Wrestling Association name, and shared Chicago with Verne Gagne.

Wilbur Snyder is interviewed by Lord Athol Layton. Courtesy Chris Swisher.

While still a key part of the promotion, Snyder avoided the traditional trappings of a promoter and pushing himself at all costs, seemingly content to work the mid-cards, particularly tag team bouts. He was no slouch, though, and in the later ’70s was still hitting flying head scissors and leapfrogging foes half his age. Snyder also resisted shoving his son, Mike, into the spotlight, when he debuted in 1974. “My father left the final decision to me, and I really seriously thought about it. I knew that I would have a lot of problems at first because after all, a lot of people would expect me to be Wilbur Snyder all over again,” Mike said in Wrestling News.

Lanny Poffo, whose father Angelo Poffo, had some famed bouts with Snyder, got to know Snyder in the mid-’70s. “There was a guy who was a fantastic looking man, excellent babyface, everything you’d ever want for the most athletic looking guy. But he smoked and drank and did everything but, he did it with discipline. He did it after the show. When he came to the matches, he was ready to wrestle,” said Poffo. “He was like the handsomest man ever.”

Billy Robinson, Wilbur Snyder

The promotion made both men rich, even with a failed attempt to invade The Sheik’s Detroit territory, and Snyder sold his share in 1983, and settled into retirement, having invested wisely, primarily in real estate.

CODA: On July 19, 2014, Wilbur Snyder will be inducted into the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame, which is a part of the National Wrestling Hall of Fame Dan Gable Museum in Waterloo, Iowa. The other members of the Class of 2014 are Scott and Rick Steiner.

TRAGOS/THESZ CLASS OF 2014 STORIES

- July 27, 2014: Road trip for a friend: A weekend at the Tragos/Thesz Hall of Fame

- July 26, 2014: Steiners headline Tragos/Thesz induction weekend

- July 17, 2014: Thesz would approve of Wilbur Snyder as a hall of famer

- July 16, 2014: Amateur days at Michigan helped shape Scott Steiner

- July 10, 2014: Larry Matysik has earned the Melby Award for wrestling journalism

- November 12, 2013: Steiners and Snyder headline 2014 Class for Tragos/Thesz Pro Hall