It is ironic that the biggest role in Hans Steinke’s film career had him under so much makeup that he was virtually unrecognizable. Yet in the ring, the 6-foot-6, 275 pound Steinke was unforgettable, dwarfing his peers.

The part that hid Steinke was in the 1933 flick Island of Lost Souls. Steinke played the lead villain named Ouran, a big ape-man seen throughout the movie. Steinke was billed just below stars Charles Laughton and Bela Lugosi. A mad doctor (Lugosi) sets up shop on an uninhabited isle, and proceeds to push the boundaries of evolution, trying to speed up the process of making beasts more man-like.

According to the press Steinke received, the ape-man gimmick wasn’t a stretch for the behemoth.

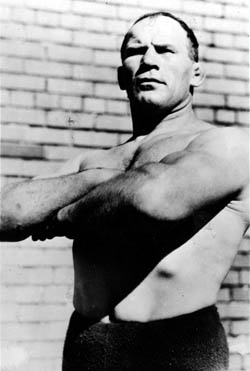

Hans Steinke. Courtesy Department of Special Collections, University Libraries of Notre Dame

“If you have seen Hans in the roped ring you can easily understand why he is in demand for certain parts in the movies. In any part that has to do with ape-men, Hans cannot be beaten for his interpretation of the part,” wrote Mike Meehan in the May 1933 issue of Boxing & Wrestling News. “Hans plays the part of an ape-man very well because he is very well fitted in a natural way for the part. Even in a match he has bearing of a big ape and the actions of his arms and shoulders remind one very much of the actions of an ape.”

Steinke would never ascend to such heights again in his film career, which started out with Yellow Ticket, and followed with Deception in 1932 (which prominently featured wrestler Nat Pendleton). Other roles for Steinke included: A Wrestler’s Bride and Sweet Cookie in 1933; 1935’s Once in a Blue Moon, where he was Count Bulba, and People Will Talk where he was Strangler Martin; Nothing Sacred in 1937, where he stretched to play a … wrestler; and 1938’s The Buccaneer, where he was uncredited as Tarsus.

Perhaps he thought the Hollywood business was on the up-and-up like wrestling? “Here’s something for the fans who think that the wrestlers take turns winning and losing,” explained the Frederick (MD) Post on June 26, 1931. “Hans Steinke, the big Dutchman, who left the ring at Carlin’s last summer because a fan called him a vile name, also walked out of the movies. The story goes that Steinke was hired to make a talkie short, but when he found out the plans called for him to lose to an unknown wrestler he simply refused. The bearded wonder, Serge Kalmikoff, was supposed to throw Steinke in the picture, but the big German would have none of it, and so Rudy LaDitzi was substituted for Steinke.”

The irony, of course, is that Steinke rarely showed any colour or acting ability as one of the most feared professional wrestlers of the 1920s or 1930s. Perhaps better said, Steinke had all the colour he needed just in his size and chiseled body.

“Steinke, no doubt, would be one of our champions if it were not for the fact that he lacks color while in the ring,” wrote Meehan in Boxing & Wrestling News. “That is, he works in a smooth and unruffled manner and does no acting of any kind. He never becomes riled at the tactics of his opponent and rarely does he throw his man out of the ring or get himself thrown out. He gives the fans the impression that there is nothing to the matches he takes part in and so the fans do not look for much of the excitement they like so well.”

Newspapermen thought very highly of Steinke, and he was considered a top contender.

“Termed the German Oak, Hans will weigh in around the 240 pound mark and what a man. Built like the rear end of a hack, this fellow Steinke is feared by all of the matmen in the racket today. He not only uses skill in his matches but his brute strength is often brought into play and when his opponent tries to get rough, look out boys, there touching off TNT,” wrote Frank Colley in the Hagerstown (MD) Daily Mail.

The Lethbridge Daily Herald wrote that Steinke was considered in the top six of grapplers in the world, in its September 16, 1924 edition. Calling Steinke “the wonder man of the mat”, the paper went on to his diet: “‘believe it or not’ he eats a ton of sausages every day. But he is no sausage himself. He stands six and a half feet in the arena and is agile as a panther.”

He was easy for promoters to promote as well. Boston-based mat majordomo Paul Bowser crowed Steinke to the Lowell (Mass.) Sun in June 12, 1934: “Back from a three days scouting trip through N.Y. and Pennsylvania wrestling circles, I find that Hans Steinke, burly German grappler, has been turned down as an immediate opponent by Champion Ed George. Steinke, one of the famous foreign stars, cornered myself and George in New York and demanded a shot at the crowd. George told Steinke to get a reputation for himself, whereupon the German offered to take on Nick Lutze, Joe Malcewicz and any other wrestler I name.”

Born in Stettin, Germany, in the mid-1890s, Steinke grew up the son of a butcher. He was a private in the German army in the First World War. After the war, he found his way into wrestling and to America in 1923.

He would battle greats like Stanislaus Zbyszko, Strangler Lewis, Man Mountain Dean, Earl McCready, Jack Taylor, Jim Browning, Ed Don George wrestling across North America. Steinke and strongman Milo Steinborn had a long series of battles as well. According to historian Steve Yohe, Steinke had a minor claim to the world title in New York in 1929, but later lost in an elimination series with Jim Londos and Dick Shikat.

The German Oak had his fans, as well. A December 14, 1927 short in The New York Times proves it: A petition from admirers of Hans Steinke, wrestler, demanding a match with Joe Stecher, was rejected and the petitioners were instructed to file a challenge in the customary way. Incidentally Secretary Bert Stand pointed out that the commission does not recognize Stecher as heavyweight wrestling champion.”

Steinke’s wrestling career lessened in the 1930s when he turned to Hollywood and acting on a more regular basis. When the work as an actor dried up, he went into the cement contracting business.

He also gave boxing a whirl, as detailed by columnist Al Warden in his syndicated column “Patrolling The Sport Highway with Al Warden” in February 1940.

Bone benders object to old boxers starting a count every time they go down under a rabbit punch.

Boxing and wrestling simply don’t mix.

Hans Steinke found that out one night in Los Angeles when after due preparation he launched what he believed would be a sustained drive for the heavyweight boxing championship. For a starter, they tossed the German in with a Negro named Tom Hawkins, and who could box like blazes.

Huge Hans lunged at Long Tom for a round and a fraction while getting his nose peppered with left jabs good and plenty.

Steinke grew tired of this before the second heat was half over … decided to return to what he knew best … pronto.

Gloves and all, he fastened a hammerlock on Hawkins.

The booing could be heard in San Francisco as Steinke glued the startled Hawkins’ shoulder blades to the canvas, but that was all right with Hans. He took his customary bows from the four sides of the ring.

Hans Steinke had won his way and in his own mind and was glad to get out of there.

Apparently, Steinke wasn’t a bad golfer either. In April 1937, he won a tournament in Santa Monica, Calif., for wrestlers. “Golf professional Stan Kertes played host to the wrestling fraternity at the Clover Field links, and the winning trophy today belonged to huge Hans Steinke, German matman. Steinke carded a 90, with Hardy Kruskamp runner-up with 94 and Jules Strongbow next at 96,” read the wire service short.

A chain smoker his whole life, Steinke died of lung cancer at age 78 on June 24, 1971 in Chicago.

Promoter Jack Pfefer addressed Steinke’s legacy in the October 1971 issue of Ring Wrestling.

“When the German Oak was at his crest he weighed 240 pounds and was a match for anybody in the business. He was known as one of the great ‘shooters,'” wrote Pfefer. “On and off the mat, Hans Steinke was a great athlete, an honest competitor, a credit to the game in which he achieved world fame.”

FILMOGRAPHY

The Buccaneer (1938)

Nothing Sacred (1937)

People Will Talk (1935)

Once in a Blue Moon (1935)

Sweet Cookie (1933)

A Wrestler’s Bride (1933)

Island of Lost Souls (1932)

Deception (1932)