Former Texas Gov. John B. Connally is in the history books on several accounts. He was U.S. secretary of the navy; he was seriously wounded by the same infamous gunfire that felled President John F. Kennedy; and he later served as secretary of the treasury.

But few wrestling fans realize they have a reason to extol Connally, who died in 1993. Connally’s official sanction, as part of his gubernatorial duties, launched then 14-year-old Susan Tex Green on her way to a career in professional wrestling.

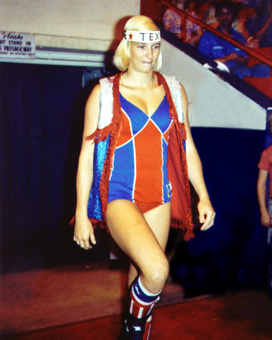

Susan Tex Green has been wrestling since she was 15. Here, she comes down the ramp at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens. Photo by Steven Johnson

“My parents had to meet with Connally to assure him that it was not a child labor situation,” Green recalled laughingly for SLAM! Wrestling. “They told him that I was just going to be wrestling in the summer or on weekends, and it wouldn’t interfere with school. So he signed a release that allowed me to do that.”

Thirty-five years later, Green is still going strong. Now a prominent trainer in South Carolina, the one-time teenage phenom is instructing male and female students in a pull-no-punches style that emphasizes hard contact, mat wrestling, and plenty of holds and counterholds.

“She was sort of like my mentor,” said former WWF women’s champion Leilani Kai. “She’s tough, she’s a very good wrestler, she’s old school, and I think she could take a moose’s head off if she wanted to.”

Moose-related physical force is not exactly what one would have expected from a young lady who barely tipped the scales at 100 pounds when she turned pro. But Green, who broke into wrestling with the help of famed Texas promoter Joe Blanchard, is uncompromising in her dedication to a traditional style of wrestling.

“It’s a reflection of the way I was taught, what I believe in, and what fans really want to see,” she said.

It’s an approach that served Green well. Growing up in Corpus Christi, Texas, she was hooked on wrestling at an early age.

Her father, a wrestling fan, took her to the shows organized by Blanchard, whose son Tully also became a mat great. Green was a fixture at weekly Thursday night matches by the age of six, and she and her dad maintained the same seats in the same row for 10 years.

A tennis player and prodigious swimmer in high school, Green admitted that she “bugged” Blanchard for years to train and wrestle. After he relented, she hit the canvas with a group that included Bob Windham, aka Blackjack Mulligan. With Connally’s authorization in hand, she got her first taste of a real match on her 15th birthday.

While she was in high school, Green estimated she wrestled about 40 pro matches, including a Christmas-time tour of Tennessee in 1970. For the most part, her unusual part-time job attracted minimal ribbing from fellow students, with one notable exception.

One day, the center on the football team started teasing Green – by then, she was “all the way up to 112 pounds. I ended up dropkicking him, and he hit the wall and knocked himself out. After that, everybody had the utmost respect for me,” she joked.

After high school, Green headed straight to Columbia, S.C., the stomping grounds of The Fabulous Moolah, the empress of women’s wrestling as unchallenged trainer, booker and organizer.

Moolah was known for taking a 30 percent cut of her girls’ payoffs. But Green realized the champion also possessed the power to make and break careers. And, once Moolah saw Green’s already well-honed ring work, she immediately sent her on the road.

From there, Green took off like a wildfire in a dry forest. While still a teenager, she possessed the aura and the polish of a veteran. Her infatuation with “selling” opponent’s moves helped to position her in the ring as a young, babyface blonde in distress.

“I was a firecracker,” she said. “I couldn’t get back to one territory before another one was calling me about something else. If I was on the West Coast, they wanted me on the East Coast. If I was in the south, they wanted me in the north.”

Want proof? Green’s parents bought her a new car for her high school graduation. Nine months later, she returned to the Texas dealership to get a larger Ford Galaxie. The salesman reasoned that Green could get good value on a trade-in, until he checked the odometer:

98,000 miles. In nine months.

“The guy just about died,” Green remembered.

Before she turned 20, she toured in Vietnam and Hong Kong. In 1972, she was in the second women’s match in Madison Square Garden – against Moolah, of course – after New York state legalized women’s wrestling.

She would battle Moolah in the old WWWF and elsewhere throughout most of the 1970s, though her favorite territory was the Oklahoma-Texas-Louisiana promotion owned by Leroy McGuirk. There, she loved squaring up against Toni Rose and Paula Kaye.

One of the regrets of many women wrestlers is the way Moolah held the world title virtually without interruption for a span of nearly 30 years.

Green did get a brief run with the belt during a two-week tour of her home state of Texas in 1975. Dallas promoter Fritz Von Erich told Moolah he wanted her to drop the title to Green for the duration of the tour, and then regain it at the end.

“She was a crowd pleaser,” wrestler Ann Casey said of Green. “When people ask me how the belt should have been handled, Sue Green is definitely one who should have held it for a while.”

Even so, Green, who at 6-foot-1 grew into one of the tallest of female grapplers, does not harbor any bitterness toward Moolah or the state of 1970s-era women’s wrestling. “I get angry when I think how much money she made off me. But she got me in the ring when I needed to be in the ring, and that was the most important thing in developing my career.”

Still Green, dubbed “The Texas Queen” by Los Angeles ring announcer Jimmy Lennon, remembers that striking out on her own as a teenager was not strictly a matter of fame, praise, and adoring crowds. The long hours on the road were tedious and difficult, and a social life was something other young women enjoyed.

“Lonely? That’s not the beginning of it,” Green said. “You have to learn to entertain yourself all the time because you’re isolated. If you had a bad day, and didn’t want to confess in the person you were with, then you were trapped.”

Further, fraternizing with your opponent in public was a strict no-no in those days of “protecting” the business. That unwritten rule led to a hysterical situation in Pine Bluff, Ark., where she was washing clothes at a laundromat with in-ring rival Rose.

Suddenly, the two heard customers in the background murmuring about matches the previous night in nearby Ft. Smith.

“Toni looked at my and her eyes said, ‘Um … oh, oh,’ ” Green said. “I pulled her into the bathroom and said, ‘Which dryer is yours? You get the car and get out of here.’ I ended up folding all of her clothes.”

Sticklers for correct punctuation might have noticed a lack of quotation marks to offset the Tex in Green’s name. There is a logical explanation – Tex is Green’s real middle name.

After headlining throughout the 1970s and 1980s, she moved to South Carolina in 1988 and started working for the state Department of Corrections, which had four Susan Greens on the payroll.

One of them had an unfortunate tendency of writing cheques of dubious value, which meant the other Susan Greens were suffering the ignominy of her misdeeds.

After being summoned by the police department late one night, Green the wrestler asked a police sergeant to figure out a way to end the cases of mistaken identity.

“I walked in, looked at the sergeant, and said, ‘What’s it going to take to make you stop calling me at 2:00 in the morning and coming down here?'” she recalled.

“Get a middle name,” he responded. “It’ll be changed in the morning,” an agreeable Green declared, and she became known officially as Tex, as she had unofficially for years.

In South Carolina, Green has been very active in the Professional Girls Wrestling Association, an independent promotion that offers all-female cards and serves as a point of entry into the profession for many aspiring women.

She was the group’s first champion, and PGWA promoter Randy Powell said at a recent convention in North Carolina that Green supplied “real wrestling credibility” to the organization.

Now a planning and development services inspector with the city of Columbia, Green trains, works out intensively, and occasionally wrestles during off hours. She oversees her students at the aptly-named Gym of Pain and Glory, which is in a converted barn on her five-acre home near Columbia, S.C.

As befits her belief in traditional-style wrestling, you won’t find high spots or G-strings on her property.

“I actually discourage all the flippings,” she said. “I want to keep it basic to the ropes and mat. The biggest high-flying move I taught anybody is the big splash or a frog splash.”

Green said that some would-be female wrestlers have dropped out after they learned what is in store for them. Two members of the University of North Carolina rugby team, for example, were amazed at how much more difficult Green-style wrestling was than their demanding sport, she said.

“I work them hard enough that they really have to want it,” she said.

It follows, then, that Green thumbs her nose at the striptease follies that make up much of women’s wrestling in owner Vince McMahon’s WWE.

“To me, the evening gown matches are totally ridiculous, but Vince pulls it off and makes money with it,” said Green, who also doesn’t care for the sexual romp storylines that involve Moolah and Mae Young. “Even with that money dangling under my nose, I wouldn’t consider it.”

Green primarily trains men – “most girls here say they don’t want to work with me because I hit too hard,” she said. One notable exception came during a match with Kai in Columbia, as Green’s supervisors in the planning department sat in the audience.

Kai and her ringside manager pounded Green after the match and left her lying in the ring. When Green reported for work the next day, her boss, alarmed at the thrashing he had witnessed the night before, told her she could take off the day with pay.

“If only he knew,” Green laughed.

SUSAN “TEX” GREEN STORIES

- June 8, 2022: Sue Green on ‘Out In The Ring’

- May 24, 2017: Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame focuses on Class of 2017

- July 15, 2009: In her toughest battle, Susan Green gains upper hand

- June 6, 2008: Susan “Tex” Green improving

- April 19, 2008: Women’s great Sue ‘Tex’ Green fights for life