This July will mark two years being clean and sober for ‘Maniac’ Matt Borne. Now 43, he has calmed his life down. Gone are the parties, the cocaine habit, replaced by a new family and a second chance.

Yet wrestling is still a part of his life, just as it has always been. The son of wrestler Tony Borne, Matt grew up in dressing rooms across the U.S., idolizing the behemoths that were his father’s friends. After more than 20 years of his own career, Borne now finds himself promoting small indy shows at a Pittsburgh bar once a month and working the occasional show.

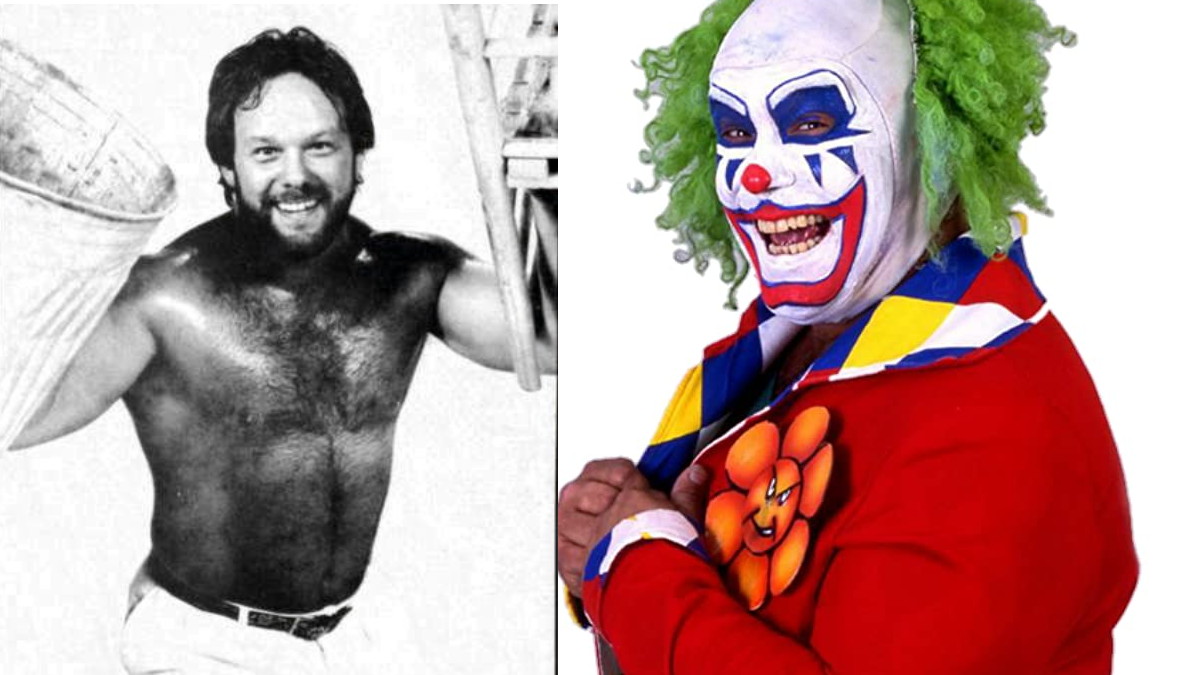

Doink the Clown, aka Matt Borne.

He can look back now on his career and see all the self-destructiveness, all the hurting and pain he caused. Time doesn’t necessarily heal all wounds, but it does allow for perspective, for contemplation of the past.

“I can remember driving down the road at the height of my career with Vince [McMahon] and I was making $10,000 a week, and I’m driving on the road and I was miserable. In all my career, I wanted to get to a certain point, and there I was — I had it. Why wasn’t I happy? I couldn’t figure it out, and nobody could have told me,” Borne told SLAM! Wrestling. “I guess I had to go through what I went through to become the type of person that I want to be.”

“I look back, and I can’t say that I would do anything different because if I had, I wouldn’t have my little six-month-old son. I’m grateful for everything I had, and everything I went through. I thank God that He carried me through the bad times because for all intents and purposes, I shouldn’t be here!”

The first step, though it is an overused cliche, is to admit that you have a problem. Borne knew he had a drug problem, and achieving success as Doink The Clown in the WWF in the mid-90s only made it bigger.

“I tried to do it myself, I tried to keep my problems a secret, which is kind of impossible to do when you’ve got drug problems. But I tried to seek help just myself, try to do it myself, but I just couldn’t do it. Finally I just decided I wanted help. I was tired of repeating the same mistakes. I guess I would have some success then I would sabotage myself.”

He checked himself into the White Deer Run rehab centre in Allenwood, Pennsylvania and found a new lease on life. He found “honest” work about a year ago as an operator at a strip mine, mining limestone, and is married for the fourth time, with a three-year-old daughter and a six-month-old son.

Borne also goes to prisons to speak to inmates about drug abuse. “That helps me a lot because if I can go in there and tell somebody my story, that there is life — learn how to live your life. I didn’t know how to live. I had to live like every day was a party and what can I do for me? What I learned, and it’s really pretty simple and ironic, the only way that I can be happy is to give of myself. If I feel myself starting to be unhappy, then I’m aware now that it’s because I’m thinking selfish thoughts.”

Like many second-generation wrestlers, Borne grew up in the business. “I was around the business at a young age and in the dressing rooms a lot. Back then, the guys were like big kids and they were always pulling ribs on each other in the dressing room, and I couldn’t wait to go to the show with my dad so I could be in the dressing room around a bunch of these big kids.”

At 13, his idol was Moondog Mayne. “Every day was like Christmas to him. He was always pulling ribs.” But today, Borne can see how the people he worshiped then affected him later. “I’m admiring this guy who happened to be an alcoholic too, but he was just a jokester, and it had quite the effect on me — maybe not all good. He had a big bearing on just my outlook on life.”

When he decided to become a pro wrestler, his father tried to discourage him. “I don’t know if he tried to discourage me or if he tried to make me make my mind up if I really wanted it. He told me I was too small, but I weighed 215 (pounds) when I started. I wasn’t too small. I think he just threw some negative at me just to see if I was really serious.”

In the end, his dad came around and helped his son become a good pro, and the advantages of being a second-generation mat warrior helped as well. “In a sense you do [have an advantage] because you understand the business a little deeper, but on the other hand, the guys in the business, especially the oldtimers, or maybe guys who are on their last legs, they see you coming up — I don’t know if I’d call it jealously, but they just automatically think that you expect things to be handed to you, which wasn’t the case. I just wanted to learn. I had to deal with a lot of bullsh*t.”

Rowdy Roddy Piper had a big influence on his early carer. “When I started, Roddy Piper just came in the Portland area and we became friends, and kind of took me under his wing.”

Over the course of his early career, he wrestled in many different territories, and had great success in Portland, Texas, Mid-South, Memphis and Mid Atlantic. Borne also did tours of Japan, Australia, Egypt and went to Europe with the WWF.

“I liked all the territories I worked in really,” he said. Texas, where he worked from 1986-1990, stands out because of the great climate, and he really liked living in Charlotte, N.C.

Borne even appeared on the first WrestleMania card, losing to WWF newcomer Ricky Steamboat early in the card, someone he had wrestled many times before in Mid Atlantic. “I felt pretty fortunate that I was able to be on the card. It was the biggest show that I had ever been on up to that point.”

Matt Borne from a couple of years ago during a tour with the B.C.-based ECCW promotion. — Courtesy ECCW

He had a short stint in WCW in 1991 as Big Josh, but things didn’t work out for him, his personal demons surfacing again.

Shortly after leaving WCW, Vince McMahon hired him to play Doink The Clown, and despite the scorn of the industry and his peers, it worked for Borne.

“The most success I ever had in the business was Doink,” Borne said. “When I started it, the only two people in the entire industry that believed in it was Vince and myself. I had a lot guys make a joke about it, nobody took it seriously. But I knew in my heart that if I could make it work with Vince, Vince was going to give it a push.”

Borne was a good choice for Doink. He was a jokester, and fun guy. “Vince McMahon just has a knack for bringing out characters in people that they maybe have a little piece of inside. He’s very creative with that, like he’s done with Steve Austin … it’s just a part of his personality exploited.”

He never doubted that he could pull off the Doink character, making it believable. “It was kind of a fine line to walk. Nothing like that had ever been done in this business before, and that’s why it was looked down upon by so many.”

His good friends Jesse Ventura and Roddy Piper both questioned his involvement in the gimmick. “Even those two guys who I looked up to, I always had them on a pedestal, even their negative outlook on what I was doing as Doink, that even didn’t deter me. I’d get off the phone with them and say ‘they just don’t know.'”

Doink took off, and while never a headliner, was a solid part of the WWF’s undercard in the mid-90s.

At WrestleMania IX in Las Vegas, Doink beat Crush with help from Steve Keirn who had been hiding out under the ring, dressed as another Doink.

Having a tag team of clowns was discussed, and attempted half-heartedly. “We did a few more times on the road. Steve Keirn was pushing for a Doink tag team, which I really didn’t want to do because I created the character, the character was created with my personality.”

Borne was fired by WWF honcho Vince McMahon at the end of 1993 for his reoccurring drug abuses — his personal problems had destroyed his business life.

“I had a very bad cocaine problem and then when Vince fired me at the end of ’93, I really went off the deep end for about a year and a half. That’s when I really tried to run from it. It kept coming back to me, it kept coming back to me.”

Seeing other people, like Keirn, Steve Lombardi and Ray Apollo portray Doink The Clown was also incredibly frustrating for Borne. Plus there were all the other independent promotions doing evil clown knock-offs. “Imitation is the biggest form of flattery, and when guys were starting to do it on the independent circuit and stuff, hey it was kind of flattering at first, but after a while, I really did get upset about it because Vince created it with me, he owned the copyright.” Borne admits that he was hurt that McMahon wouldn’t bring him back as Doink, even after cleaning up his act.

Doink was great for his career, a peak that he scaled only to fall off the other side. “Win or lose, I had a lot of success with Doink and I feel grateful for getting that opportunity.”

It’s all behind him now. “I look at it as a learning experience. I’m a better person for it.”

Now helping out young wrestlers in his own little promotion, Borne can offer a lot of wisdom. “I can see guys when they’re thinking about the business and their careers, and the long way that they shouldn’t. I can help them. But you can’t help somebody with a drug problem unless they want help.”

Never a flashing, high-spot type of wrestler, Borne would also like to see young wrestlers better schooled at the fundamentals. “I look at it being in the business from a different perspective, helping younger guys because I think it’s a dying art. Guys are learning the mechanics of the business before they learn how to work. They’re two different things. Anybody can do the mechanics, but to get out there and work isn’t just going through gymnastics.”

Talking about his career is a release for Borne, a chance to share and help others. Just talking about the past seems to brighten his future.

“One of the biggest things was dealing with all the loss that I had, that I created for myself. That was one of the biggest obstacles that I had to do once I got clean, was to put this stuff behind me. I can’t dwell on things that I’ve lost, but what I can do is create a future and that’s what I’m doing now.”

MORE BORNE LINKS

- June 21, 2023: ‘Dark Side of the Ring’ returns to form with exposé on Matt Borne/Doink the Clown

- June 28, 2013: Matt Borne, original Doink the Clown, dead at 56

- Aug. 27, 2010: ‘Tough’ Tony Borne dead at 84

- Apr. 12, 2010: Doink the Clown ‘Reborne Again’