Editor’s note: Problematic language may remain in vintage quotations and has been kept to maintain historical accuracy of the speaker’s words.

In the list of incredible athletes that came out of the American boarding schools for Indigenous peoples there is little debate on who the greatest athlete to graduate from the system: Jim Thorpe.

An Olympic champion, star on the football field and baseball diamond, and so much more, Thorpe’s story has been told in depth, including the spectacular biography Path Lit by Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe by author David Maraniss.

But worth mentioning in the next breath is Mayes McLain, whose tale is lesser known — and involves a lot more time in the wrestling ring than Thorpe (who did a couple of bouts at most).

Born on April 16, 1905, in Pryor, Oklahoma, Mayes was the youngest of six children, though a brother and sister died in infancy. His parents were originally from Texas, and they married in Pryor. His father, Pleas L. McLain, was a white farmer of Scotch-Irish ancestry, and his mother, Martha, was Cherokee.

McLain talked about his upbringing in a July 2, 1970 interview with the Atlanta Journal. Pryor Creek, Oklahoma, was Cherokee territory. “When they drove all the Indians into the black land of Oklahoma and put to farming it, the Osages were put one place and the Cherokees another,” McLain said. “Well, the Osages struck oil on theirs. They’re known as the rich Indians.” (Martin Scorsese’s film Killers of the Flower Moon details some of that part of history.)

He played football at Pryor Creek. A wealthy Osage sponsor helped get him to the Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas, where Dick Hanley was the football coach (and who would later coach at Northwestern).

The Haskell Institute was opened by the US government in 1894, and was a vocational school running up to Grade 12, that intended to make the Indigenous children assimilate into the white population. There were many similar schools across the country, including the Carlisle Indian School, in Pennsylvania, where Thorpe attended.

A key factor, though, is that the more athletic students often stayed a year or two after they should have graduated, meaning they were college age – which came in handy when the teams competed against other colleges. By today’s standards, it was closer to a junior college, where the top students and athletes would get a chance to move on to a proper university for their final few years, and earn a degree.

Frank W. McDonald was the athletic director at the Haskell Institute, and was interviewed in the Des Moines Register in 1990. “I can remember walking into a fourth-grade classroom and seeing a 290-pound Indian from Alaska. Some of the students were older than I was,” he said.

“There weren’t as many rules in those days,” added McDonald. The success of the football team resulted in the construction of a 10,500 seat football stadium.

Again, by today’s standards, many of the gimmicks for the touring teams are downright wrong, like the players getting off the train wearing traditional blankets and then walking through town, just to drum up publicity.

The boarding school teams saw success competing against and beating well-known colleges like Michigan State and Notre Dame. After the new stadium was opened in October 1926, McDonald noted that representatives from 75 tribes assembled to mark the occasion and watch the team win 36-0 against Bucknell. “They came for peace, not war, to greet each other in the name of the pigskin,” said McDonald. The big schools wanted the teams like Haskell and Carlisle to come to town as they sold tickets.

McLain was 20 when he started at Haskell, and immediately on the field, he was virtually unstoppable, and played both offense and defense. Statistics aren’t always as reliable from those days, but consider: In the 1926 season, he scored 253 points (38 touchdowns, 19 extra point kicks, and two field goals) while playing for the Haskell Indians Varsity, and the team was the highest-scoring in the US for the second-straight year; the team had a 12-0-1 record, and the tie came on a day that McLain sat out with a leg injury; in one game, he scored 50 of Haskell’s 55 points, and in another, he accounted for 27 of 30; he was a National Honor Selection to All-American Second-Team as a fullback.

Enrolling at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, for the 1928 season, there was plenty of hype, and McLain helped the team to a winning record for the first time in a few years. And they drew fans.

When Iowa played at Chicago’s Soldier Field in October 1928, The New York Times wrote: “Not since the days of Red Grange has Chicago and the Big Ten been as intensely interested in a single gridiron luminary as they are in that giant Indian line smasher, Mayes McLain of Iowa. . . . Weighing more than 215 pounds and standing six feet two inches, McLain, who led in individual scoring while at Haskell two years ago by burning up 253 points in thirteen games, is a terrific driver.”

After that one season, McLain was done, as the Big Ten faculty eligibility committee decided that his time was up, as the seasons at Haskell counted. Later, McLain was implicated in a booster group payoff scandal, where he was paid $60 a month “for allegedly taking a ‘real estate census’ of Iowa City” but apparently never did any actual work, whereas other teammates did do work for which they were paid.

Professional football was not yet the juggernaut that it is today, but McLain gave it a whirl (an apparent sidestep into baseball apparently not working out).

He played for the Portsmouth Spartans, based in Ohio, and the forerunners of the Detroit Lions. Often called Chief McLain in articles, he scored four rushing touchdowns and three receiving touchdowns during the 1930 season. The next year, he only played in a single game for the Spartans, but was in nine contests for the Staten Island Stapletons, and another few games for the St. Louis Gunners.

There was a lot of football those years, McLain told the Atlanta Journal. He’d “just knock all the bruises from one side to the other” and keep playing. By his estimate, McLain made $4,500 for a 20-game season with all the different teams.

“That was pretty good for the times, but I was born 40 years too soon,” he said, “before the bonuses, before plane travel, before the good hotels, meal money and pension funds.”

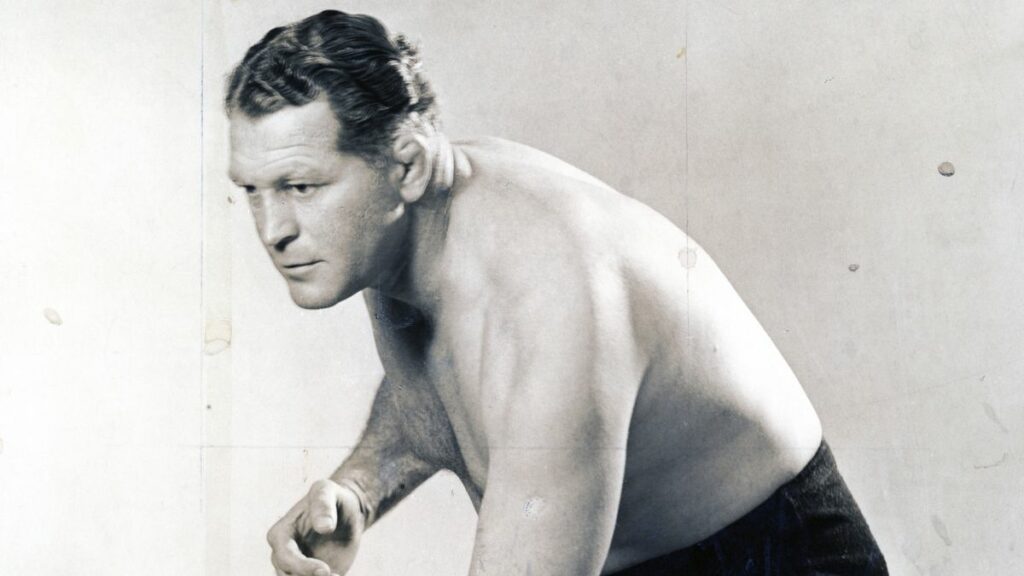

Mayes McLain in an early publicity photo, 1933.

McLain took up pro wrestling next, and begins appearing on cards in March 1933. A big man, at about 240 pounds, he competed as a heavyweight and took advantage of his name value to be on cards in big and small arenas across the US and Canada, plus a trip to Australia and New Zealand.

Any of the ballyhoo on McLain in the newspapers would invariably mention his football background and that he, like the famed Gus Sonnenberg, used the flying tackle as well.

Pitted against Joe Savoldi in September 1933, the Toronto Star quoted McLain: “Naturally, I regard Savoldi as a great wrestler; in fact, a great all-round athlete. At the same time, it is apparent that he has been lucky in winning some of his bouts this year and he can’t expect the luck to last forever.”

A year later, another Toronto newspaper, The Globe, wrote about Mayes on Feb 1, 1934: “McLain has been in wrestling long enough to qualify as a worthy opponent for any heavyweight in the sport. During the early part of his career he set something of a record for quick finishes, disposing of his opponents in the average time of ten minutes. Then the caliber of opponents became better as he moved up among the heavyweight contenders, but he has acquitted himself creditably against the best in the world.”

Mayes McLain shakes hands with Lionel Conacher.

Football was never far from McLain, though. In the fall of 1933, the famed Lionel Conacher amassed a pretty unique collection of players for a pro team that started out at Maple Leaf Stadium in Toronto called the Crosse & Blackwell Chefs. Some were well known football players, but there were a few wrestlers too, like McLain, Joe Savoldi, Ernie Zeller, Alex Kasaboski and Wilbur Smith, as well as hockey players like Eddie Convey, Duke McCurry, and Lionel’s brother, Charlie, who was completely new to football.

Fast and nimble, Mayes was a babyface for the most part, and didn’t play up the “Native-American gimmick,” though his spirit name, “White Turkey” would have been a natural for a heel.

Mayes McLain, a smiling babyface

“Fans Like Him” noted The Globe on Sep. 22, 1936, with a small photo. “Football and wrestling have combined to establish Mayes McLain as a very popular athlete in Toronto.” McLain had been in town a few years earlier, battling nasties like Ted Cox and Hans Steinke.

High Point, NC, March 12, 1937

World War II interrupted more than just pro wrestling, of course. Starting in late 1941, McLain worked in Los Angeles at Lockheed Aircraft Corporation as a policeman.

While in L.A., McLain also found work as a stuntman on movie sets; he’d been in 1936’s The Magnificent Brute as well, though uncredited.

Post-war, it seems that McLain was a tad more villainous, before calling it quits in 1953.

A more mature Mayes McLain. Photo courtesy Chris Swisher

In February 1951, McLain was unmasked as The Masked Manager, by British Empire champion Whipper Billy Watson at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens. The Whip got the masked man in his dreaded Canuck Commando hold, rendering him unconscious, at which point Watson and referee Ted Thomas took the hood off — despite the best efforts of The Masked Marvel to turn the tide in favor of his manager during the bout in front of 8,000 or so fans. The Masked Marvel himself would be unmasked later that year as Lou “Shoulders” Newman.

Later that year, in June 1951, McLain found himself in a London, Ontario, court, along with promoter Frank Tunney. Plaintiffs Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Edwards alleged that, during a show on February 22, McLain “viciously assaulted” her by striking her in the face with his first. She alleged that she was knocked to the ground “without explanation or justification.” The Edwards wanted $936. Magistrate Donald Menzies dismissed the assault charge and suggested that it could be a civil matter.

Mayes McLain is ready for action. Photo courtesy Chris Swisher

In his Byrd’s-Eye View column in the Winston-Salem newspaper, Carlton Byrd celebrated McLain in a loving piece on Valentine’s Day 1955. Looking back on wrestlers he enjoyed, Byrd noted that McLain “could recite Shakespeare for endless hours” and wrote:

McLain was my favorite. He had the distinction of being named to different positions on All-America teams two years running. At Haskell Institute he was a tackle, and at the University of Iowa he was a fullback. He differed from most grunt-and-groan artists in that he frequented libraries in the cities where he wrestled. It wasn’t unusual to see McLain sitting in the local library and reading Shakespeare or other literary works the entire afternoon on the Fridays he wrestled here.

“McLain went so far as to recite his literary learnings in the ring. During a bout with Scotty Dawkins one night, he came up off the floor after being felled by a haymaker to the head and roared: “Before my body I cast my warlike shield; lay on, MacDuff, and damned be him who first cries, ‘Hold, enough.'” McLain rushed into Dawkins and was proceeding to knock him into oblivious when the Scot retreated and shouted to the referee, “Make him open his fists up.”

“Shame on you,” taunted McLain. “Don’t you know you are never supposed to end a sentence with a preposition.”

McLain was still involved with wrestling post 1953, including time as a referee, mainly near his Georgia home.

Away from the ring, the Atlanta Constitution wrote that McLain had “interest in the welfare of the American Indian … through the years, and he was affiliated with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.”

He worked at, and retired from, Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, in Marietta, Georgia, where he was an inspector.

Mayes Watt McLain died on March 11, 1983, in Marietta.

The funeral for McLain was at Dobbins Funeral Home in Marietta, and he was buried in Mountain View Cemetery.

The obituary listed that McLain had two children: daughter Rita Haynes of Marietta and Charles W. Barrett or Smyrna, Georgia. He was married to actress Viola Weller for a time.

On March 21, 1987, the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame, in Lawrence, Kansas, enshrined McLain; also in the class that year were Pete Houser, Arthur S. Bensell and Sonny Sixkiller.

RELATED LINKS

- SlamWrestling.net’s Indigenous Peoples story archives

- The Sporting Connection archives