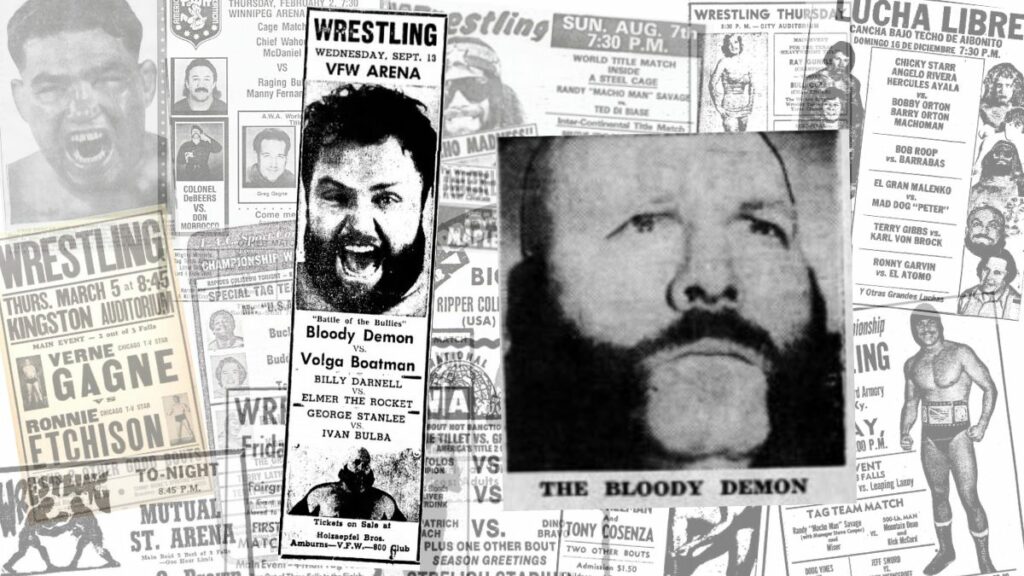

It’s that time again — time to find a random wrestling card from history and shake it for all it’s worth to see what comes out. This time we’re heading back over 70 years to check out this brief card from September 13, 1950, in Sandusky, Ohio. This show was wrestled under the auspices of the Terminal Athletic Club — the Toledo, Ohio wrestling office.

Here’s the card with the results:

- Volga Boatman and the Bloody Demon, double DQ

- “Handsome” Billy Darnell def. Elmer, the Rocket

- Ivan Bulba def. Dale Wayne (sub for George Stanlee)

This show took place at the VFW Sports Arena in Sandusky, Ohio. The arena was a popular venue for boxing and wrestling cards in the area at the time and is now VFW Post 2529.

Teaming up with veterans’ welfare organizations was a commonplace way for promoters to promote wrestling. Many of the local promoters associated with Jack Pfefer used connections with the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) or American Legion to stage bouts.

This is a fine example of the breed, with a stubby three-match card the ideal length on Wednesday evening in mid-September. The Toledo office had severed ties with Columbus, Ohio’s Al Haft, a few years prior, instead opting to rely on Jack Pfefer‘s talent, who are here on this card in spades.

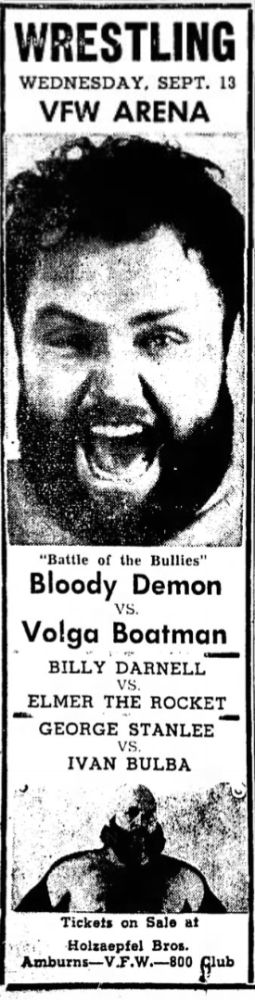

The main event for the evening is a battle of the beasts — two monsters that weren’t afraid to play rough. First up is the “Bloody Demon,” a Californian grappler by the name of Jack O’Brien (not to be confused with another Jack O’Brien, a star in Mexico whose career was winding down by 1950).

“Bloody Demon” is just one name O’Brien used in his lengthy career, with other options including the “Demon,” “California Demon,” and “Ivan Zdanoff,” amongst others. The name “Bloody Demon” wasn’t even the full name — that was the very striking “Bloody Demon from Death Valley.”

Bloody Demon

Jack O’Brien was also a multiple-time world champion, laying claim to the Jack Pfefer version of the World Heavyweight Championship at least four times in the late 1940s and into 1950, though this may be inaccurate as there were numerous splinters to the long-serving title.

The Pfefer version of the championship is a story in and of itself. The title dates back to around 1939 when Bobby Bruns defeated Maurice Boyer in Bridgeport, CT. The title was actually the New England version of the World Light Heavyweight Championship, but after Bruns’ victory, the nomenclature was altered to remove the “Light” aspect of the belt. Interestingly, the famed “Strangler” Lewis World Heavyweight Championship, would switch places, becoming recognized as the World Junior Heavyweight Championship.

The Pfefer World title.

O’Brien’s opponent for the evening was the Volga Boatman. Occasionally billed as “the Original Volga Boatman,” he was nearly seven feet tall and topped the scales north of 300 lbs. He was actually Frank Ramey, a seasoned grappler who also wrestled under the names Elmer Estep, Hillbilly Elmer, and the Ozark Giant.

The Volga Boatman name and trope was a popular one with Pfefer — probably because it hit so close to home. While he was born in Warsaw, his family uprooted early and often, with the eventual destination Ukraine — namely, Dnipropetrovsk (modern-day Dnipro). But stops along the way seem to include stops in Russia, including Novgorod.

The song “Volga Boatman” was a popular tune in Russia from the late 19th century, with two movies following in the 1930s, so the name, themes, and characters were easily understood by Pfefer — never the best at creating wrestling aliases.

The Sandusky Register article hyping the card noted that the promoters had moved the front row back several feet. Apparently, both the Boatman and the Demon were so riotous that the safety of the fans was paramount. “Demon and Boatman are two of the biggest grapplers in the business and both are ruffians of the first order,” the article noted.

The Volga Boatman

In the end, the additional steps were futile. as the two bullies gave special referee Martino Angelo — a Hamilton, Ontario-born junior heavyweight wrestler and multiple-time junior/light heavyweight title claimant — too much of the business, with both men disqualified.

Also on this card is the rather wonderfully named “Elmer, the Rocket.” Elmer was Herb Larson, another Hamilton, Ontario-born wrestler. Larson was a natural fit with the Pfefer clan. A gifted athlete from his youth, Larson also dreamed of landing a vocal role in an opera company — something close to Pfefer’s heart.

Pfefer’s life in the United States began in an opera company, with the diminutive Pfefer serving as a pianist and background performer for two seasons with the Russian Grand Opera Company. But, like Larson, the money was too good in wrestling, and within five years, Pfefer was one of the top managers of talent in the country.

Herb was profiled in the April 1952 edition of NWA Official Wrestling, with the article noting that while he was gaining ground on the stages of theatres and opera houses, he was even more successful on the mat in the “grunt-and-groan” game:

“Right now it is neck and neck as to which career is progressing more rapidly,” the story read. “While Herb has begun to show real promise as an operatic contender, he has gone even further on the mat. His fast, scientific style has made him an overnight sensation in wrestling arenas and on television.”

Larson was never a main eventer under the “Elmer, the Rocket” name, but he remained popular with crowds who appreciated his scientific knowledge of wrestling — and his exceptional speed which rivalled Marvin ‘Atomic” Mercer, who was a popular mainstay in Al Haft’s promotion.

Despite his popularity, however, Larson could never really reach the pinnacle of the sport, something that doesn’t appear to have bothered him.

“I had a good career out of it. I made a little money,” he confessed in this 2010 Slam obituary by Greg Oliver. “I didn’t have no title runs. I wouldn’t trade wrestling for any other kind of living.”

Herb Larson

Elmer, the Rocket’s opponent was Billy Darnell — the favorite of the “bobby-soxers.”

Darnell was at one time Buddy Rogers’ “brother,” but was more frequently his favorite opponent, with the two wrestling at least 187 times, according to the website WrestlingData, though others have cataloged at least 200 matches altogether.

Initially joining up with Buddy Rogers in Texas, the pair eventually proved a major success for Jack Pfefer and Hugh Nichols in California.

“[Rogers] went in there first and then I came in,” Darnell recalled in a 2008 obituary, written by Steve Johnson. “He had the slave girl, Helen Hild, the girl wrestler. Then I came in there. I became junior heavyweight champion and Buddy was a heavyweight; he was a little bigger.”

Bill Melby and Billy Darnell

But it wasn’t just California and Ohio fans that fell in love with the handsome grappler. He also struck up a popular tag team with Bill Melby, and later worked behind the scenes in St. Louis and in Indiana.

“I was just a kid and didn’t understand what I was watching, but I guess it was the smoothness, the flow that made it special … the way they took the crowd up and down,” recalled veteran wrestler and trainer Les Thatcher in the same Slam obituary. “I told Billy Darnell in Mobile (Alabama) a couple of years ago that their matches are one of the reasons I was in the business.”

One interesting name on this card is George Stanlee. Billed at points as both “Gorgeous” George Stanlee and “Mr. America,” George was an amalgamation of two exceptionally popular grapplers: George Wagner and strongman Gene Stanlee.

To be honest, I’m not sure who George Stanlee is. I don’t believe he is any relation to either Gene or Steve Stanlee (both actually named Zygowicz), nor is it Bob Stanlee, another kayfabe brother. If anyone has any information on George’s identity please reach out on Twitter (@cory_m_santos, cheap plug) I’d love to know.

Fortunately, Stanlee didn’t make the show and was replaced by a standby grappler, Dale Wayne.

Wayne was a fairly local wrestler with considerable regional experience. Based out of Detroit, Michigan, Wayne was 230 lbs. master of the sleeper hold and a former light heavyweight boxer. This dynamic combination of skill and force made him a regular feature on cards across the Midwest — and even further afield in places like Florida.

One of those far-flung locations was scenic Blytheville, Arkansas. The local paper, The Courier News, noted in June of 1948. That Wayne was “a toughie with a long line of followers in this vicinity.”

Despite his pedigree, Wayne was also serving as a referee in the area for promoters Tony DeMore and Johnny Nichols. I guess that explains how Stanlee was so easy to replace at the last minute.

Wayne’s opponent for the evening was “Ivan Bulba, the Mad Russian from Minsk.” A hulking, hairy, and out-of-control wildman, the Bulba character was actually John Shaw, a Texas-based wrestler, former policeman, and rancher. Shaw was rough-and-ready in the ring — something that would anger the fans to no end. Recalling his (lack of) popularity with crowds.

In a 1989 Associated Press obituary, his widow, Margie Shaw, recalled quizzing her beloved about a strange series of scars covering his body:

“So I asked him what happened, and he told me they were from people in the stands scratching him with their soda bottle caps as he went by because he had been so mean inside the ring,” she recalled.

“Ivan — that’s what we called him — really knew how to work up the crowd. They’d get furious.”

Jack Pfefer would remain a constant presence in Ohio for about another six months, with the partnership ending in late April 1951, though the fallout wasn’t nearly as severe as in other territories.

Pfefer was especially talented in being chased from town, with notable examples including Nashville, Tennessee (with the equally diminutive Christine “Teeny” Jarrett close behind in the 1960s) and in Ft. Worth, Texas — after promoter I.G. McElyea pulled a gun on Pfefer — exasperated by the Polish loudmouth’s arrogance, vulgarity, and overall bossiness in the 1940s.

Despite the slight, Pfefer would continue to successfully operate in the peripheries of the wrestling world, usually working in fairly good graces with many other promoters throughout the 1950s (but not all, right Mr. Quinn?). He would find success with a new batch of recruits, including impressive names like Ricki Starr, Hans Schmidt, and the Fargo Brothers, Jackie and Don.

But as the National Wrestling Alliance expanded its reach, Pfefer would find himself further isolated, sticking to close allies in places like Boston, Chicago, and Nashville. But that’s a story for another day — and another card.

RELATED LINK