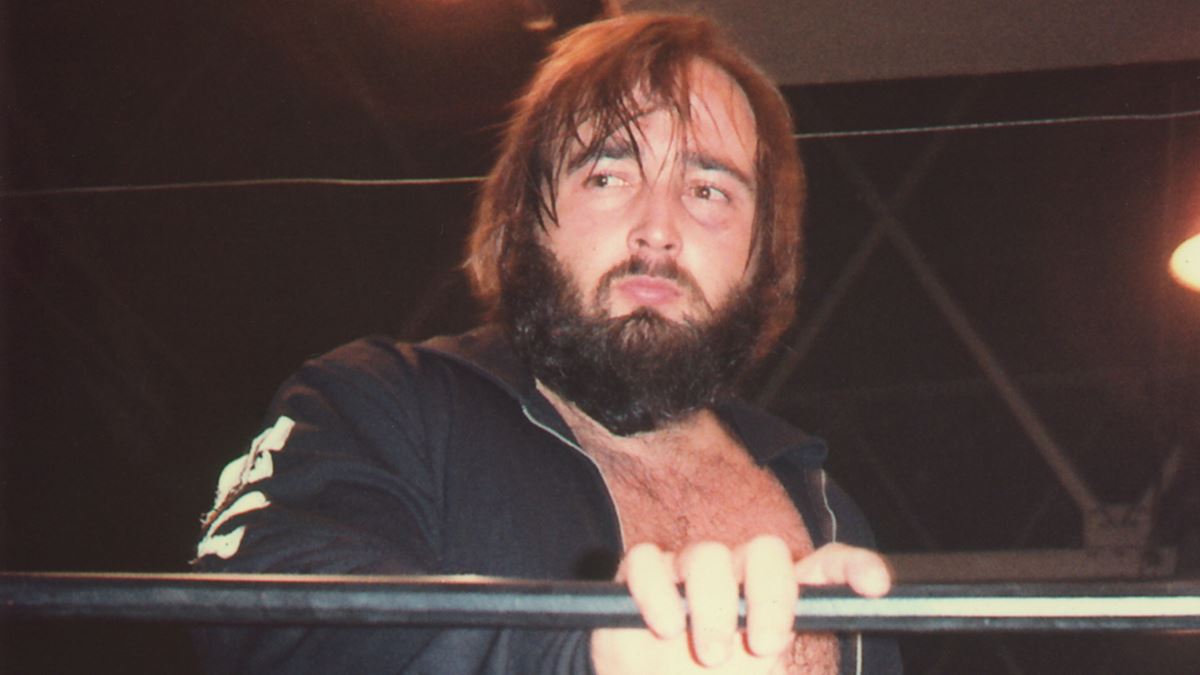

Killer Tim Brooks, the unpredictable madman with the long, scraggly hair, and an unkempt beard, who headlined many territories across the United States, and wrestled around the world, has died after a lengthy battle against cancer. He was 72.

The family announced his death on June 30, 2020, via Facebook, and his son Clayton’s page:

It is with a heavy heart that we the Brooks family announce that our father, loving husband, brother and friend has made his depart from this earth to the heavens. From the Brooks family we want to say thank you for all the prayers, love and support through these terrible times. Dad was the toughest man I have ever met he fought cancer like I have seen no other. With all the accomplishments he has made through his 73 years on this earth from being a army veteran of the Vietnam war to holding just about every championship belt through professional wrestling and a hall-of-famer. Most of all he was a God-fearing man a wonderful husband to his wife of 13 years Julie, the best father and grandfather to us kids. He will be missed dearly by so many. We will keep everybody updated on arrangements as they’re made thanks again for the love and support.

#killertimbrooks #lovinghusband #lovingdad

Sincerely Brooks family

Those who saw Timmy Brooks looking up at the lights continually in the Detroit territory, circa 1972, probably would not have predicted the success “Killer” would have in the ring.

Key to his breakout was changing up his look, from clean-cut babyface, to the leather jacket-clad crazy man. They were lessons he absorbed at the learning tree of The Sheik.

With his 6-foot-1, 240-260-pound frame, Brooks portrayed someone who could be just as comfortable in a barroom brawl as a wrestling bout. “I think I had a rugged look, with the tattoos, the beard, the long hair. I was a fighter, I was not a technical technician,” Brooks explained in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. “I was a furniture mover, a fighter. I think what the people liked about me, when they knew I was going to have a match, it was going to be a fight. It was going to be chaos. It was going to be wild. It wasn’t going to be your average wrestling match. Also, I think they knew I was going to take it to that babyface’s ass.”

Unlike his cousin, Dick Murdoch, Tim Brooks took his time getting into pro wrestling. Sure, they were close growing up, often wrestling on a mat with their uncle Farmer Jones in the backyard of his Texas home after the sun went down. But whereas Murdoch started refereeing by age 14, and followed in his father Frankie Hill Murdoch’s steps as a wrestler shortly thereafter, Brooks didn’t get into the mat wars until after a stint in the army, from 1963 to 1966. Brooks was Military Police. “We went into a lot of bars and whorehouses and such and broke fights up. I don’t know if it prepared me [for wrestling], but it got me being active in a rough kind of way. The real craziness came in wrestling, not in the army.”

Brooks didn’t think wrestling was for him. He was in Amarillo for his aunt’s funeral when Murdoch made an interesting proposal. “When the funeral was over, Dick said, ‘Why don’t you come and travel with me and go to a few shows? We can drink some beer and have some fun,'” recalled Brooks. Every night, the wrestlers would show him a few skills.

His first match was in Odessa, Texas in 1969, and he had to be convinced by Murdoch and Terry Funk to replace a no-show. “They said ‘We’ll take care of you.’ That’s the most famous words in wrestling,” laughed Brooks, remembering the 15-man battle royal. “They just beat the hell out of me, man, and threw me over the top rope. That was my first match. That was my beginning.”

By the early ’70s, Brooks had made it to Detroit and settled in. It was a good location to find work in Michigan, Ohio, West Virginia, Ontario and Quebec, and even WWWF TV in Hamburg and Philadelphia. He might not have been on top, but he was learning.

The Sheik Ed Farhat is the guy who really schooled Brooks. “He was my father in pro wrestling. He gave me my first break,” Brooks said. “He helped because he showed me, he taught me, he made me watch his matches, he talked to me.” Later in his stay in Detroit, Brooks became The Sheik’s tag team partner, which propelled him up the card to face top names like Bobo Brazil, Tex McKenzie and Pampero Firpo.

Killer Tim Brooks with a Men’s Wrestling Award at the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in Las Vegas in 2006.

When 1976 came along, Brooks decided to hit the road again. “You can only stay in a territory for so long. When I was The Sheik’s partner, I would be the guy to lose and do the jobs. Once you do so many jobs, you need to move on somewhere else because the people know that that’s what is going to happen.”

Brooks felt he had the skills to be a major figure in any promotion. “My strength was being capable of going out on a card and I could get heat. I don’t care who was on the card, or where it was … my time being with The Sheik made me capable of going out and following a lot of matches and getting heat when there were good people on the card, good heels.”

After returning to Amarillo for a stint (returning to Texas would become a regular trend), Brooks went to Calgary for Stampede Wrestling. “I can say nothing but good things about the guy,” said “Cowboy” Dan Kroffat, who battled Brooks over the North American title. “Easy to work with. He even had a look about him that was far out there. In some ways, he didn’t even look like a wrestler; he looked like a coal miner.”

In Houston, he was Killer “Hit Man” Brooks. He also had great success in Japan, often teaming with Bruiser Brody, and with runs as both All Japan Heavyweight Champion and All Japan Tag Team Champion.

In Georgia, he famously sold the National title to Larry Zbyszko after beating Paul Orndorff.

“Killer Brooks’ character was basically like he was. He was a soulless guy who just didn’t give a damn. He just liked getting in rough fights. He wasn’t a great athlete,” said Zbyszko. “What you saw on TV was what Killer Brooks was. He was one of these guys who wasn’t a great athlete, but he was just a tough kind of guy who didn’t care. There were some guys who if their teeth got knocked out, they’d cry like babies and run to the dentist to get them fixed. Killer Brooks is one of these guys, he didn’t care if his hair was scraggly, he was half-bald and greasy. He didn’t care if his teeth were half knocked out or brown. He just didn’t care. He was one of these guys, like a lot of wrestlers, that if they were in normal, every day society, they would probably be locked away.”

In Portland, Brooks dominated the territory with Roddy Piper, once memorably bringing out a wheelbarrow full of title belts on TV. It’s also the place where the wild life really took over. “Bruiser Brody was probably my biggest friend in wrestling, but Roddy was really a good friend. I enjoyed the time that I spent around Roddy Piper. We had fun in our apartment that we shared. We traveled together and had fun on the road. We had fun in the ring as a tag team. We just enjoyed everything we were doing,” Brooks said. “That took plenty of time off my life! If I die tomorrow, I’ll blame it on Roddy Piper.”

Years later, Brooks recognized the errors of his ways. “There was an outlaw in me and I didn’t always do what everybody wanted me to do. I’ll be the first to admit that I don’t do drugs any more, but I had a drug problem. That didn’t help me, you know what I mean? Drugs didn’t do anything for me. It hurt me. Sometimes people can be their own worst enemy, cut their nose off to spite their face, jump out of the fucking skillet into the fire.” His drug of choice? “I didn’t have a drug of choice. I did everything, all different kinds of drugs. I never did inject any drugs, but I swallowed, snorted, smoked.”

Dutch Savage was one of those promoters who had a rough time with Brooks and Piper. “They did a lot of toot together,” Savage said, explaining that their temperament changed when high. “It’s like a dynamite keg all the time. You had to walk around them with kid gloves.”

As a booker, manager and friend, Gary Hart saw all the sides of Brooks. “Killer Brooks had a tremendous drug problem. You name it, he took it,” Hart said. “He was a complete and total druggie in every way. My rule with Tim was, do not get high before the matches. I don’t care what you do after the matches, as long as your name don’t get in the newspaper or on the radio, you do what you want. But of that generation, there were quite a few guys that were doing Quaaludes, cocaine, marijuana, acid, like the rest of the world.”

A family crisis forced him to clean up after 25 years of drug abuse. Both Brooks and his second wife had a drug problem, and squealed to authorities on each other, while filing for divorce. The court ordered them to clean up, or give up their two sons, aged five and six months. Brooks checked into a veteran’s hospital and had a 60-day lock-up that got him dry; then had a six-month stay for “mental hygiene.” Both he and his wife cleaned up and they went back to court, where the judge sent them to his chambers with instructions to reconcile if they wanted their sons out of protective services. “I guess we talked about 20 minutes. We came back out and told the judge that we wanted to make a go of our marriage, we wanted to stay together, and most of all, we wanted our children back,” recalled Brooks. “My boys were there within an hour, and the judge released us.”

Brooks ran a wrestling school in Waxahachie, Texas, for a time. Both of his sons, Timothy (“Timo”) and Clayton, learned the ropes and wrestled for a time.

His daughter, though, had a longer career, even if they were not aware of their relationship until January 2010. Tonya DuRoche was the only daughter of long-time wrestler Sandy Partlow, who wrestled primarily in the Midwest. She kept the information on Tonya’s father from her for years, even after Tonya had a reasonable in-ring career of her own.

Tim Brooks and his daughter Tonya DuRoche.

“We’ve been a part of each other’s lives for almost 9 years but he and I are so much alike you’d never know that I wasn’t raised by him,” wrote DuRoche in early 2019. “He’s such a character and he and my Daughter have a bond that’s indescribable. She thinks it’s hilarious when he pretends to scold me or get after me. They are quite the pair. I almost gave up in trying to find my real father but when I wanted to give up I kept looking at my 8 year old daughter and she is the main reason that I kept searching for him, for her. I felt she had the right to know her ancestry, family health history and so much more. Luckily I found him and he accepted us as has the entire family and we love him.”

The news of Brooks’ failing health — he was diabetic, had bariatric surgery in 2010, and a knee replaced — resonated throughout the Texas wrestling scene. He trained many wrestlers at his school, opening every Saturday morning (he set up at trade shows as a day job for many years until his knees and ankles prevented that), and running a live show for 200 or so fans once a month.

Wrestler Tygress Lourdes (K Kreymer), who runs the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in Wichita Falls, Texas, with her husband Johnny Mantell, called Brooks her “Wrestling Dad” and managed to carve out a few hours with him before he was moved to hospice care at the end of February 2019. She spoke for many, as friends had to come to terms with the inevitable, saying she is “at peace with his decision” to stop chemotherapy and enter hospice care. “Hard to believe the decisions made in just one week but I understand his reasoning and I can’t say I wouldn’t do the same,” she wrote.

His fading health allowed him to do the rounds of many of the Texas promotions, most of which presented him with awards to mark his years in the wrestling game. The Cauliflower Alley Club presented Brooks with a Men’s Wrestling Award in 2006, and he was a part of the Class of 2020 for the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame; knowing that he was in poor health, Brooks’ family and the PWHF conspired to surprise him with an early induction amidst the COVID-19 pandemic on May 17, 2020.

Funeral arrangements are not known at this time.

— with files from Steven Johnson

[modula id=”10287″]

RELATED LINK