Many Canadians are aware of the real-life Rocky saga played out by former Canadian heavyweight boxing champion George Chuvalo in the 1960s and 1970s. Chuvalo, though more a capable boxer than an elite one, had a strong winning record over the course of a career spanning more than two decades, and he became an international name by facing Muhammad Ali twice in the late ’60s and early ’70s — both times standing up to a beating of 12 rounds or more before losing a lopsided decision. But while it was certainly Chuvalo’s toughness that earned him a place in the hearts of Canadians and the respect of boxing fans everywhere, it can be argued that it was another Canadian who played a key role in ensuring Chuvalo’s efforts would be seen on the biggest stage possible.

Ali was a world heavyweight champion at the top of his game going into 1966. After taking the title from Sonny Liston two years earlier, his only defenses — in May and November of 1965, against Liston and Floyd Patterson — had taken place in the United States. But by early 1966 Ali’s position on the Vietnam War and the draft, along with his conversion to Islam, made him something of a pariah as far as U.S. media were concerned; and the controversy that followed Ali everywhere he went in the United States scared some commissions and promoters off from wanting to sanction or promote his fights. As a result, four of Ali’s title defenses in 1966 took place outside the United States.

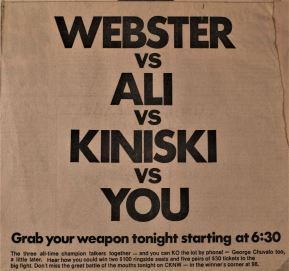

The first took place in Toronto when Frank Tunney, who promoted boxing shows as well as wrestling, had the opportunity of a lifetime and hosted a Muhammad Ali title defense at Maple Leaf Gardens on March 29, 1966. Ali found a mainly receptive population in Southern Ontario during the height of his opposition to the Vietnam War, and his opponent was three-time Canadian champion Chuvalo — a competitor whose toughness was beyond question but who was given little chance to upend Ali. In order to drum up interest in the Ali–Chuvalo encounter — which took place, amid the 1960s turmoil, on just 17 days’ notice — Tunney turned to the best mouth he knew: Canada’s Greatest Athlete, Gene Kiniski.

Kiniski had been a Toronto headliner on and off for nearly a decade, engaging in fierce encounters against the likes of Pat O’Connor, Lou Thesz, Antonino Rocca, and Bulldog Brower and lighting up Maple Leaf Gardens with a long and legendary series of matches against career rival Whipper Billy Watson. Equally memorable to Torontonians were Kiniski’s efforts in tag team battles in partnership with the likes of Don Leo Jonathan, Fritz von Erich, Waldo von Erich, and Hard Boiled Haggerty. Kiniski had also earned a good share of press in Toronto for his in-ring shenanigans and his wit, and he was a popular guest on non-wrestling TV shows such as CFTO-TV’s Sports Hot Seat. Canadian sports broadcasting veteran Bernie Pascall, who worked for CFTO in the 1960s, first met Kiniski when the latter was in Toronto in the mid-1960s for an appearance on the program. He recalls, “He was just a master and just manipulated the high-profile Toronto media as only Gene could.”

George Chuvalo and Gene Kiniski in Toronto, before Chuvalo’s first fight with Muhammad Ali. Photo by Roger Baker

Kiniski was on top of the wrestling world as NWA World Heavyweight champion in March of 1966 when it was announced that Tunney — a good friend of Kiniski’s — would be promoting an Ali-Chuvalo title match at Maple Leaf Gardens. The fight would not be broadcast in the United States, and promotion was aimed solely at a Canadian audience — particularly those situated around Toronto. To drum up ticket sales, a series of radio “debates” between Ali and Kiniski was set up; and while recordings of the 1966 “Battle of the Mouths” debates are hard to come by and it is unclear how many of the 13,540 spectators’ tickets or thousands of closed-circuit tickets Gene Kiniski helped to sell, his role in the 1966 “Battle of the Mouths” is well-remembered.

Though overmatched, Chuvalo managed to become the first boxer to last 15 rounds with Ali, and he maintained a busy schedule in the aftermath of his world title loss, winning the majority of his matches but losing one-sided contests — while staying on his feet — against the likes of Joe Frazier or George Foreman. Ali, meanwhile, was stripped of his title and was sentenced to prison in 1967 as a result of his refusal to be drafted. He appealed but did not return to the ring until late 1970. After coming back from the layoff, Ali performed well in 1971 despite losing a 15-round decision to heavyweight champion Joe Frazier in March.

On May 1, 1972, Chuvalo got a second chance to face Ali, again in Canada, but this time in Vancouver. By then Ali was back in the good graces of the U.S. mainstream and was on fire as a boxing attraction in pursuit of the heavyweight title that had been stripped from him. Chuvalo, meanwhile, remained hugely popular in Canada and was known throughout boxing as someone who could tough out a beating against the best.

Ali–Chuvalo II was a fight that definitely could sell itself in the Canadian market. Even so, local promoter Murray Pezim must have been delighted when he learned Ali–Kiniski II would be occurring as a preliminary to Ali–Chuvalo II, which took place at the Pacific Coliseum and ended with a result not too different from that of Ali–Chuvalo I.

Sports Illustrated writer Robert F. Jones reported, on May 15, 1972, that Ali, just prior to his rematch with Chuvalo, “appeared on a [CKNW Radio] talk show emanating from [Vancouver] in what was billed as the ‘Battle of the Windbags.’ His opponent was Gene Kiniski, a Vancouver wrestler whose cauliflower ears and zigzag nose belied his quick wit and quicker tongue. After an hour and a quarter of outrageous hyperbole from both contestants, the show’s host, a jolly Scot named Jack Webster, declared himself the winner. Ali smiled and shook his head. ‘Kiniski,’ he said, ‘if only there was a white heavyweight boxer like you from Alabama or Mississippi, we could make us a skillion dollars.'”

Veteran British Columbia broadcast personality Wayne Cox says a highlight of the show came after Ali said wrestling was phony and challenged Kiniski to take it outside. “Gene said, ‘I would love to once you release me from the handcuffs that are holding me down in this chair,'” recalls Cox. “[Right after that,] there was a whole bunch of thumping noise on the desk, and then the show was over.”

Pascall, who relocated to British Columbia in 1969, says Webster, who worked with him for a time at BCTV, “always mentioned that one of the biggest moments and highest-rated radio programs [he ever did was when] Ali and Gene were the featured guests.” Concerning Kiniski’s part in the promotion of a boxing show in Vancouver, Pascall adds, “Even when Muhammad Ali was front and center, they were leaning towards Gene to help promote Muhammad Ali” — who was perhaps the highest-profile athlete in the world at the time.

Following their second and final convergence in 1972, Chuvalo, Kiniski, and Ali all enjoyed further years of notable success. After his loss to Ali in Vancouver, Chuvalo closed out his career with seven consecutive knockout or technical knockout victories and retired with the Canadian heavyweight boxing title; and Kiniski — 43 years old at the time of Ali–Chuvalo II — still had over a dozen wrestling title runs ahead of him. Ali, of course, would regain the world heavyweight boxing title in his classic rope-a-dope encounter with George Foreman in 1974 and would enjoy several more years probably on a level of his own among athletes as far as his fame and his ability to mesmerize the masses — both in the ring and on the mic — were concerned. Yet there are plenty of people who to this day argue that, at least for brief stretches in Toronto and Vancouver in 1966 and again in 1972, Ali met his match in Gene Kiniski.

RELATED LINKS

- Gene Kiniski story archive

- Mar. 11, 2024: Muhammad Ali to be inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame

- July 31, 2023: Muhammad Ali joins WWE Champions

- June 4, 2016: Wrestling world remembers Muhammad Ali

- The Sporting Connection archive