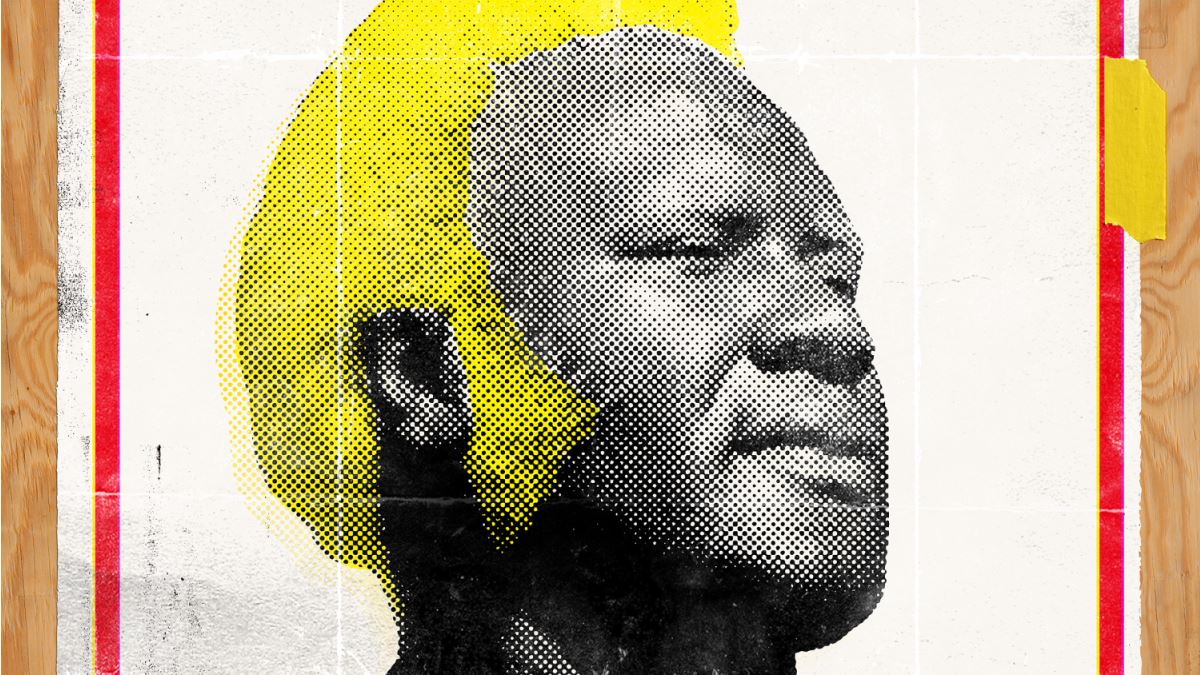

Review: Sweet Daddy Siki documentary ‘relevant and important’

Invariably, wrestling biographies mix drama, old school hype and oddball minutiae and on this count, Sweet Daddy Siki hits it out of the park. This thoughtful feature length biography for television holds up a mirror to the unique journey that brought Sweet Daddy Siki from sharecropper’s son to headliner during the 1960s and ’70s. At the height of his career, the self styled “ladies’ pet and the men’s regret” played the self absorbed heel as well as any wrestler of his era or any other. Bleached blonde hair, sequins, bridal gloves, sunglasses, hand mirrors and a strut backed up by serious athletic prowess, Buddy Rogers and Gorgeous George were inspired parts of his gimmick.

But what made him unique, and this story so fascinating, was his struggle – as one of the first African American heels in the game, we learn that Siki came to prominence during an era when segregation, racism and intolerance were the real villains. Physically impressive, remarkably athletic, with a gift for histrionic flair, Siki was an above average performer to begin with. But as a black heel in the 1950s and 1960s, when just skin colour was more than enough to get you killed, and your business involved riling crowds in the American south, it took serious courage to play the part, let alone navigate the prejudice that permeated the business itself. Carefully crafted, the film grabs you by the throat when the man’s real battles are brought to bear. To his credit, in the heat of the civil rights movement, Siki found a way to work, survive, excel and become, years later, a symbol of perseverance, change and and decency.

Director Harv Glazer (Van Wilder: Freshman Year, Vampire Apocalypse) and his team do a rock solid job structuring this intriguing retrospective. For wrestling junkies who appreciate beautifully restored photographs and long buried action and interview footage, the doc is a goldmine. Against this backdrop, Siki tells his own story alongside a cast of wrestling’s who’s who who all testify to the man’s skill and influence. And while it’s impressive seeing Bruno Sammartino, Bret “Hitman” Hart and Adam “Edge” Copeland all give the man his due as a performer, most fascinating are the cultural insights offered up. Along with Hart, Jet Star, and Rocky and Ricky Johnson, assorted historians and social anthropologists help connect Siki’s personal struggle to the era itself.

So when Rocky Johnson proudly describes Siki as the Ali of his day, and tells us that he molded his son, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, in Siki’s image, we’re given context. For Johnson, a fellow African American, Siki was clearly a role model. His gimmick was subordinate to no one; as wrestling impresario Dan Lovranski tells it, unlike the Junkyard Dog, there were no chains around Sweet Daddy’s neck. Siki’s gimmick was loud, proud, and defiant to the core. Yes he played the villain’s part, but never the fool — full credit to the filmmakers for finding and including an archival interview clip of Siki calling out a chubby white manager for racially demeaning mic work. While the context is muddy, the implications are not — Siki took no shit and was more than ready to put assholes in their place and still sell tickets.

The film tracks Siki’s ascendance to stardom from hardscrabble roots. The son of a serially abusive Texan sharecropper, Siki describes an gallingly impoverished childhood: picking cotton, witnessing the repeated physical abuse of his mother, being abandoned on a regular basis, it’s an exhaustive list. Yet Sweet Daddy does not look back in anger. “That’s just the way it was,” he reasons. But social anthropologist Will Strickland provides the bite — sharecropping was a form of slavery, Siki was born into it, the road ahead of him was all uphill.

As expected, the film treats us to a bevy of road stories. In the early days, to offset minuscule payoffs, Siki would dumpster dive for food or hope to find roadkill on the highway. But there’s no sense of embarrassment or shame suggested — Siki knew how to survive and wrestling offered hope. His big break came when he hit the mid-west and was featured the DuMont Network. National exposure made him a household name, the paycheques improved. Yet during one integrated match, the archival play by play calls attention to his skin colour as an attempt to what? Justify the anomaly to a white audience? It’s not difficult to imagine who owned a TV at the time and who didn’t. Yet Siki endured. Among other notable commentators, Bernice Carnegie, the co-founder of the prestigious Herbert H. Carnegie Future Aces Foundation, sheds light on the positive impact Siki had on media and what his image must have meant to young African Americans who would otherwise not have seen a black success story on national television. The future Rocky Johnsons of the world had their role model.

Worth the price of admission alone is a story that features Siki walking us through his becoming the first African American wrestler to earn a world title shot, against Buddy Rogers, in Greensboro, North Carolina, only to have the Ku Klux Klan threaten his life if he even touched Rogers. How he conducted himself in the heat of it all speaks to the man’s character. And when Pinball Clemons summons Rosa Parks’ name in explaining the fallout, you know you’re in a meaningful story about real issues and a true fighting spirit. And Siki is fully aware of his contribution to the game — in his own small way, he shows great pride in describing how his title shot with Rogers opened the door for other mixed matches in the Greensboro area. In truth, it would have been good to know who followed him and when. But the wrestling world favours an oral history, and these details have likely been lost to time. But it’s enough that Siki tells it. He was there.

Siki eventually moved to Toronto where he set down roots. As Ricky Johnson eloquently put it, Frank Tunney looked at Siki and didn’t see black but saw green and a long term partnership was born. Toronto, it turned out, was a more tolerant place to work and live. Long story short, this film is worth watching — it’s extremely entertaining, beautifully shot and full of insights into the journey of a gentle, thoughtful man who became the hero not just to his own story but to virtually everyone who helps tell it. If there’s one shortcoming, it’s that racism within the industry could have been more rigorously explored. How did Siki personally deal with it? Surely there were confrontations with white wrestlers or promoters. But at 83, he seems guarded to a fault; willing to report, but not vent, complain or expose, traits that were likely the reason for his longevity. Besides, Siki was a man of action. It was, and still is, up to his fans to call him hero.

So whether or not you loved or hated Sweet Daddy Siki in his prime, see this movie. It’s relevant and important. At a time when social division and racial tension have returned to the headlines, you’ll learn something about what it means to take the highroad.

Sweet Daddy Siki premieres tonight, Sunday, June 11, 2017, on CBC’s Documentary Channel at 9 pm ET / 10 pm PT.

ADDENDUM: In late 2020, Sweet Daddy Siki was added to Amazon Prime in the United States. For more on the film there, click here.

RELATED LINKS