By GREG OLIVER & STEVE JOHNSON – SlamWrestling

The passing today of George “The Animal” Steele at age 79 did not come as a surprise. Word circulated quickly earlier this week that he had been moved to hospice care and did not have much time left. What is surprising to a lot of people is to learn the true story of Jim Myers, the man who became “The Animal.”

Myers was born April 16, 1937 in Detroit, Michigan, and was a good amateur wrestler and football player growing up in Madison Heights, Michigan. He also excelled at baseball, basketball and track. Knee problems prevented his days as a Spartan on the gridiron at Michigan State University from taking off, so he turned to teaching and coaching football and wrestling at Madison High School in Madison Heights, Michigan — and he’d eventually end up in the Michigan High School Coaches Hall of Fame and the Michigan High School Football Coaches Hall of Fame.

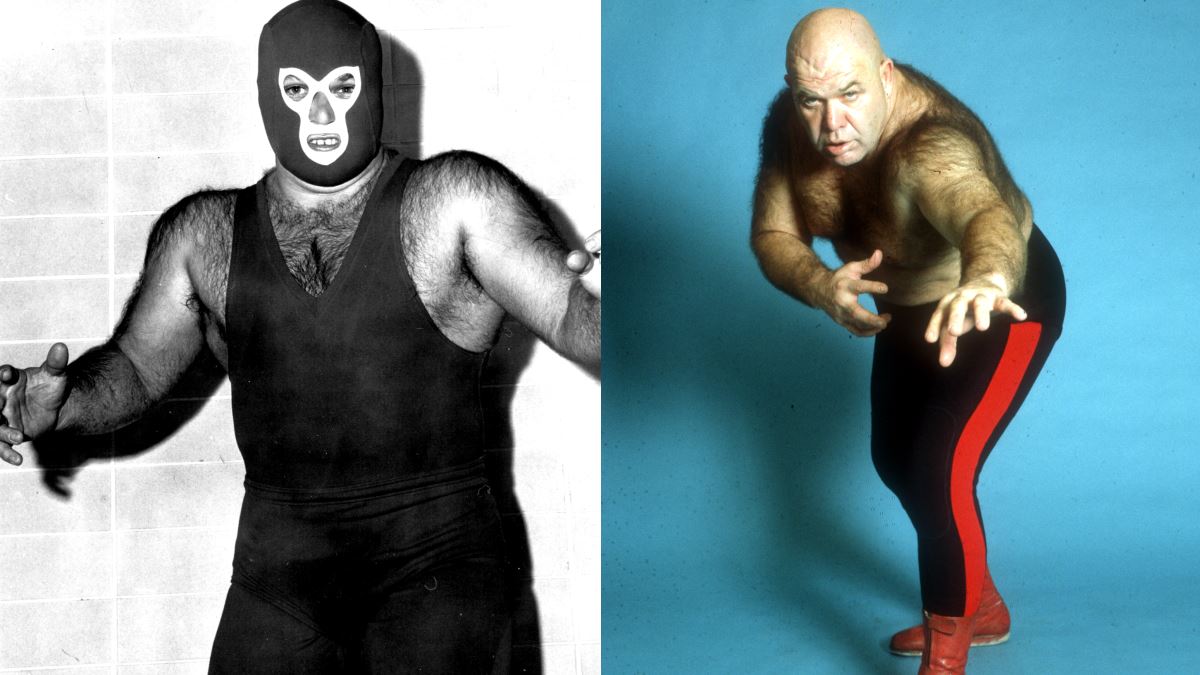

When Steele first entered pro wrestling, no one knew what he looked like. He started as the masked Student in the Detroit area around 1962. The disguise helped him hide his real identity of Jim Myers, local schoolteacher and coach, while he worked out with Gino Brito and other wrestlers. “There was Jim ‘The Brute’ Bernard, George Steele — Jim Myers then — George Cannon, myself, Tony Parisi, a couple of others,” Brito recalled. “It was an old church there, in the basement, we had the whole basement to ourselves. We had weights and everything.”

Classic George “The Animal” Steele. Courtesy of the Wrestling Revue Archives

Steele’s shift to the ranks of professional wrestling was financially motivated. “I made $4,300 a year teaching when I first started,” Myers recalled in a 2004 interview. “My first summer wrestling, I made $22,000.” Bruno Sammartino scouted him in Detroit, and brought him to Pittsburgh and the WWWF as Steele in 1967. Named after the Steel City, Steele was a brutal, killer heel at first. A generation of fans who knew him only from his guttural grunts would be surprised to learn he did his own promo work in Pittsburgh. “The way the guy looked, he had a look, much like Brute Bernard, much like Abdullah, in a different way, but had that scary persona about him,” said Gary Hart, who managed him as the Student, and thought his teaching job kept his act from wearing thin. “He wasn’t on TV every week. You got to see him in the summer time. You got to see him around Christmas, on holidays when he would take off.”

Steele relished the change in scenery from school to the ring. “In all of wrestling, I may have been the luckiest person. A lot of guys had to go from one territory to the other. I would just teach and, on the weekends, go back in the Northeast, which would have the biggest paychecks. And I wasn’t there all the time, so I didn’t get stale.”

Of course, with George Steele, one word springs to mind — turnbuckle. “The Animal” had a habit of ripping apart turnbuckle pads with his bare teeth to testify to his madness. And guess what? It wasn’t an act. “I said, ‘How the hell do you chew through leather turnbuckles like that?’ ” asked friend and referee Dick Woehrle. “I took my thumb and ran it over his teeth. They were like razor blades! I said, ‘My God, aren’t you afraid you’re going to bite your tongue off?’ ”

Well, if he did, it would have bled green. Steele used green breath mints to tint his tongue in the school color of Michigan State, his alma mater. “He had the green tongue, he was just a good heel,” said Frank Durso, a regular in Pittsburgh, where Steele made his first big splash. “His face is what got the people mad at him. He really didn’t talk nasty to the fans, but they just disliked him because of the way he looked.”

The turnbuckle entrée started by accident. In Pittsburgh, someone tossed a small, promotional couch pillow at him in the ring one night. “I took a bite out of it, tore it up, threw it up in the air and people started going nuts. This was live TV. Eventually, I put the pillow over this fellow’s head. The stuff was floating down like snow,” Steele said. Someone — he thinks it was Tony Parisi — joked backstage that maybe he could eat a turnbuckle next. When a match with Chief Jay Strongbow was going nowhere, Steele looked at a turnbuckle and said to himself, “I wonder…” Bingo! A legend was born. But Steele is absolutely clear about one thing — despite the green tongue and knife-edged chompers, he was not a gimmick wrestler. “There’s two people in this body. The persona I use in the ring, I don’t practice it. I’ve never planned it.”

Veteran Davey O’Hannon, who has known him for years, agreed that The Animal was no gimmick. “There were heels that the fans would go to and get close to. George, on the other hand, had the fans really wary of him, really afraid of him, because he was that scary a heel,” O’Hannon said. “People didn’t want to approach him because they didn’t know what they were going to get. They weren’t positive about this guy. He had a look of that Hannibal Lechter kind of personality.”

Known for his flying hammerlock, Steele got regular billing against top WWWF draws like Sammartino, Pedro Morales, and Strongbow. “In the early years I hated working with George ‘The Animal’ Steele because the guy scared the hell out of me,” said former WWF ring announcer Gary Michael Cappetta, “and he can still do a good job of it when he’s in character today.”

Steele wasn’t about to take guff from referees or stinkin’ athletic commissioners, either. Woehrle refereed a match one night in Philadelphia where Steele was in full animal attitude. “The head commissioner happened to be sitting there at ringside and he’s got his $400 suit on, and George is throwing stuffing all over him,” Woehrle said. The commissioner told Woehrle to stop the match, and the ref consulted with Steele. “I finally said, ‘Look, George, the commissioner said don’t throw shit on him like that.’ ‘Screw him!’ he said, and he goes over and rips open another turnbuckle with his teeth, grabs a handful of stuffing, and throws it all over the commissioner.” Woehrle finally disqualified Steele, who responded by popping him in full view of the ref’s daughter and friends. “Oh, George did not like that,” Woehrle said.

When the WWWF went national in the mid-1980s, Steele became a full-time wrestler and a feud with Nikolai Volkoff, the Iron Sheik, and Fred Blassie turned him into a fan favorite. “One of the funniest matches I remember with George is that after he turned, he came into a six-man tag match with Jim Brunzell and myself, and wore the Killer Bee mask,” said Brian Blair. “He was a tough guy; he was more of a brawler. But for him to all of a sudden become a good guy — he was better as the bad guy.” Steele agrees, and, similar to why he took up wrestling in the fist place, points to the bottom line. “I had gone from bring one of the wildest heels in the history of the wrestling to a cartoon character. I love working heel but the cartoon character helped us improve our lifestyle.” He also battled Randy Savage over Miss Elizabeth, and made a brief comeback in 1999 as one of the Oddities. “Once Vince mellowed, softened his image for marketing purposes, the people took to him, they liked George. People like bizarre, they like oddities,” Hart said.

Away from the ring, Steele had a major role in the 1994 film Ed Wood, under director Tim Burton. Myers played Tor Johnson, a wrestler who had been in a number of films by the director Ed Wood. He later appeared in other films, but nothing anywhere close to that level.

For the last number of years, Myers lived in Florida, and made regular appearances at wrestling events and fan fests. He was a major supporter of the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame, serving on its board of directors and helping to establish induction rules. Steele was inducted into the PWHF in 2005, and the WWE Hall of Fame honored him the same year. He also published his autobiography, Animal.

Myers was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in the late 1980s. In a 2010 interview, he addressed what the disease did to him at GeorgeTheAnimalSteele.com: “I had Crohn’s disease. They didn’t expect me to live. They gave me six months to live. Eighteen years ago, I moved to Florida for the tranquility and figured I’d probably die there. God had a better plan.”

A devout Christian and vocal about his beliefs, both about religion and health, Steele was at time a polarizing figure — but always a memorable one. He leaves behind his wife Pat, whom he met while at Michigan State, and their children, Dennis, Randy, and Felicia.

RELATED LINK