Canada has always had an impressive roster of great homegrown wrestling talent. Before the First World War, Canadians such as Montreal’s lightweight star Eugene Tremblay were already claiming world’s championship honours. Others, such as Ottawa middleweight George Walker, were beginning to make the successful transition from the amateur to the professional ranks. What Canada lacked, though, was a really good heavyweight.

Enter Jack Taylor.

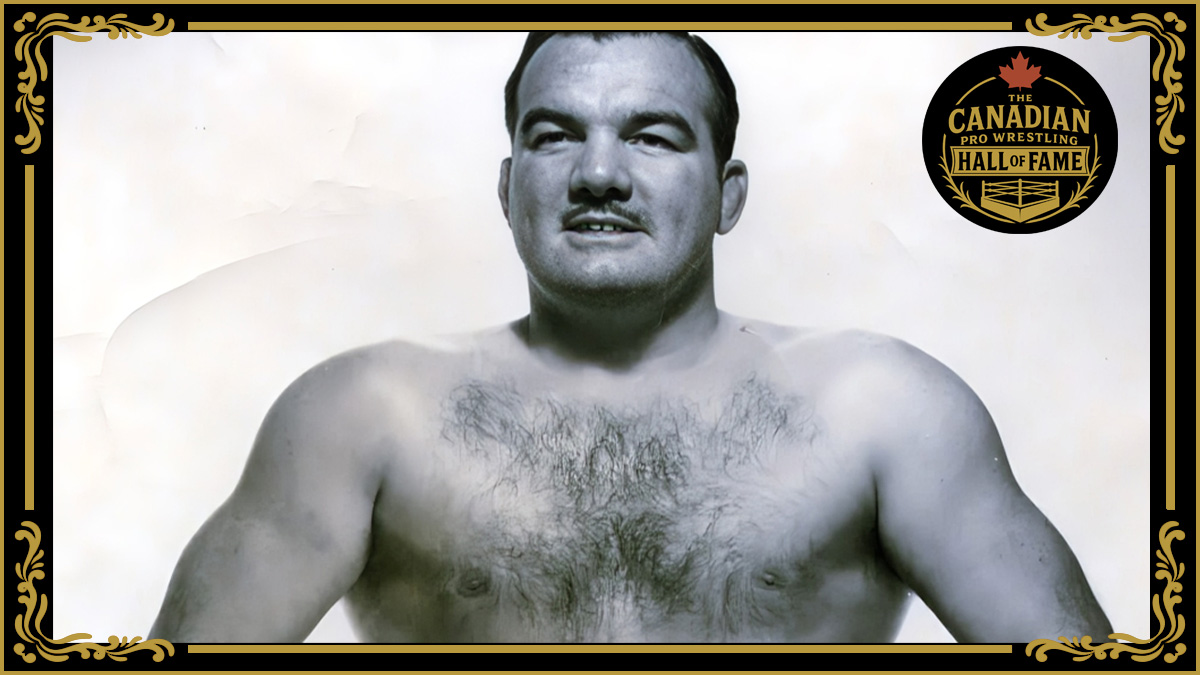

Though his name is not widely known among Canadian wrestling fans today, Jack Taylor was the king of Canadian professional wrestlers for more than two decades. As an athlete, Taylor was the central figure in two distinct epochs: the era of mat-oriented professional catch-as-catch-can wrestling and the era of “modern-style” professional wrestling, the latter of which he helped introduce to fans across the country. He was also a trainer for, or inspiration to, a number of future grapplers who would have a lasting impact on wrestling in the country.

May 19th marks the 60th anniversary of Taylor’s passing.

Born in Bruce County, Ontario in 1887, Taylor made his way west in his early 20s. At the time, Canada’s prairie provinces were a major destination for agricultural settlers. For small registration fee, and a lot of work, you could take possession, and eventual title to, 160 acres of land. Taylor settled on a homestead in Saskatchewan and soon made the acquaintance of Clarence Eklund, who was farming near Moose Jaw. Eklund, a light-heavyweight wrestler, was making a name for himself in the region and agreed to take the young, athletic, but as-then untutored, Taylor under his wing.

In addition to farming, Taylor served a short stint on the Lethbridge police force, and it was in southern Alberta that his career as a professional really took off. After bouts with the local “Cowboy” Jack Ellison, he attracted the attention of several well-known American wrestlers including Oscar Wasem, Bob Managoff and John Berg, all of whom went down to defeat at the hands of the rising Canadian star.

Soon, bigger game was coming his way. Taylor’s most notable early encounters were with Charles Cutler, who he faced on four separate occasions in Western Canada. By 1914, with Frank Gotch having stepped away from active wrestling, Cutler emerged as the leading claimant to the world’s catch-as-catch-can wrestling title. On November 25, Taylor defeated Cutler in Winnipeg via a controversial disqualification for an illegal stranglehold. Although a “win” on paper, it did not earn the Canadian title recognition — nor did he put much effort into claiming Cutler’s laurels. What it did do, however, was catapult Taylor into the top ranks of the heavyweight grapplers on the continent.

More top-flight competition followed in Cutler’s wake. Between the end of 1914 and the fall of 1915, Taylor defeated Jim Esson, the Scottish heavyweight who won the prestigious (and competitively legitimate) Alhambra tournament in 1908, the Seattle physician Dr. B.F. Roller, and Jess Westergaard.

The conventional historical narrative asserts that, following the second Gotch-Hackenschmidt match in 1911, and certainly following Gotch’s “retirement” in 1913, interest in wresting fell off steeply. Historian Mike Chapman asserts that after 1913, “it was not only the end of [Gotch’s] official career, it would mark the steady decline in popularity of the entire sport of professional wrestling.” While Chapman’s overarching thesis was that none could fill Gotch’s shoes, others, including scribe Jonathan Snowden, contend that rumors of behind-the-scenes chicanery in the 1911 match with Hackenschmidt (much of it orchestrated by Gotch and his handlers) “did more to damage wrestling in America than 100 newspaper exposes.”

Whichever interpretation you prefer, the American narrative did not apply to Western Canada. With Taylor at the fore, the prairie provinces saw more heavyweight action than at any time in the past. When he wasn’t taking on some of the continent’s best, Taylor continued to dispose of second raters. When they weren’t around, he took to the ring with members of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces who were in training for deployment to the battlefields of Europe. During a stint in Saskatoon during the summer of 1915, he offered $5 to any man who could come along and last one minute with him on the mat. In one day he disposed of 18 men in 15 minutes. Nobody collected the prize.

The First World War, more than anything else, help put the pinch on wrestling in Canada. Taylor relocated to the American west during the late fall of 1915 (and later enlisted with the American forces). Over the next few years he faced virtually all of the continent’s top wrestlers — except those that laid claim to the world’s championship. Despite repeated overtures to Earl Caddock and Ed “Strangler” Lewis, Taylor was denied a chance to contest for world honours.

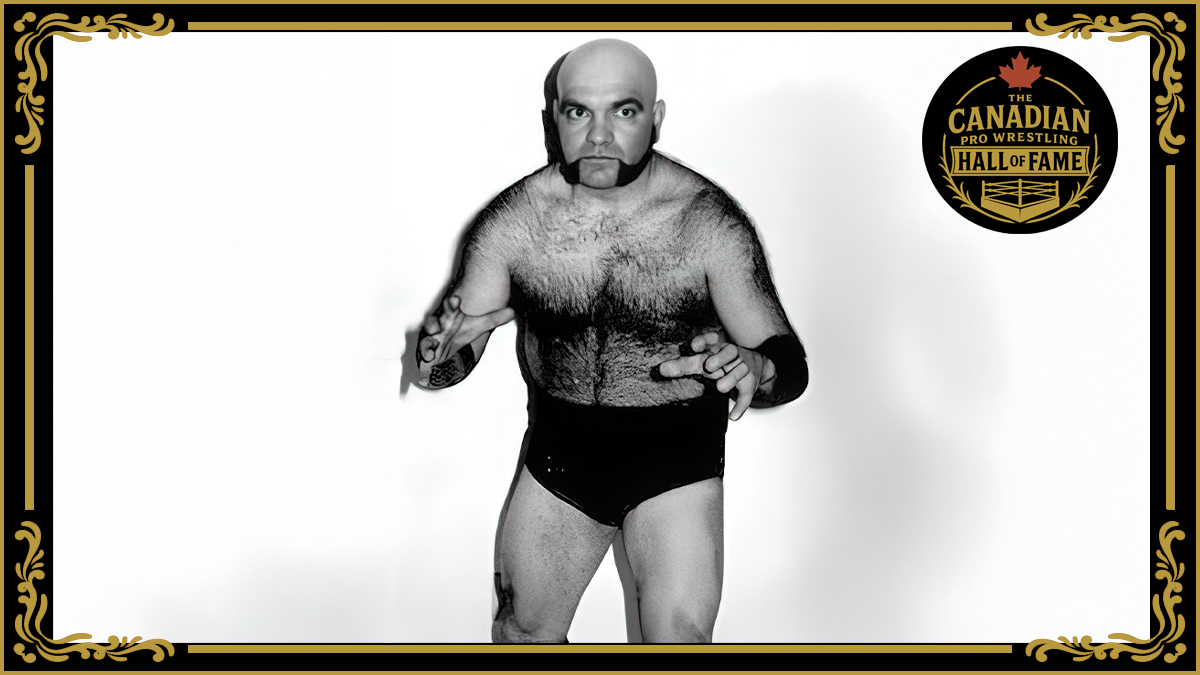

With concerted attempts by American wrestling cartels to secure firm control over the lucrative world’s heavyweight title, Taylor earned an odious reputation as somebody who would not play ball. Along with Marin Plestina, who he frequently wrestled, Taylor became one of the continent’s more well-known “trustbusters.”

After the war ended, Taylor made some appearances in Vancouver before returning to his old stomping ground of the Canadian Prairies in the summer of 1922. The big Canadian’s homecoming brought the sport to never-before-seen heights. Historian Greg Oliver, in his book The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Canadians asserts that, “It is hard for today’s fan to understand the importance of a wrestler like Jack Taylor in the 1920s. He was the wrestling star in Canada.”

In Winnipeg, where Taylor took up residence, old attendance records toppled. Though his inaugural showing against Jatindra Gobar drew a slim house for the local Empire Athletic Club, things soon picked up. Cards, staged on roughly a monthly basis, regularly began attracting between 2,000 and 3,000 spectators. Never had professional wrestling drawn such numbers, with such frequency, in the city. Taylor’s two matches with Wladek Zbyszko, in particular, pulled fans to the city’s Board of Trade Building, with attendance in both instances numbering around 4,000.

Taylor did not limit his appearances to Manitoba’s metropolis. He appeared throughout the province, as well as in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Although virtually all of the big cities served as ports of call, no town seemed too small for Taylor to make an appearance in. When he could not find a suitable heavyweight, he would line up light-heavies and middleweights and face them one after another.

Much of the promotion around Taylor during this period centred on one objective: securing a match with champion Ed “Strangler” Lewis. That never happened. A bout with Sandow-Lewis combine crony Dick Daviscourt in Winnipeg on May 8 1924, billed as an elimination contest for a title shot, saw Taylor come out on the losing end. Daviscourt got the Winnipeg title match but, not unsurprisingly, the event turned out to be a financial bust for local promoter D’Arcy McIlroy. Taylor continued to wrestle throughout the Prairies for several more months, but his momentum was on the wane.

For the next several years, Taylor made appearances throughout North America, but his career lacked a clear direction. During this period, professional wrestling was rapidly evolving in the United States, with new and spectacular moves replacing older, mat-based catch-as-catch-can methods. It was in this budding environment that Taylor would find new lease and further cement his position as Canada’s first great home grown heavyweight star.

By 1929, wrestling had long been dead in Southern Ontario. Visionary promoter Ivan Michailoff, having seen what the introduction of “new” methods could do for business in the United States, decided that Ontario was ready for a similar revival. Jack Taylor, who had recently completed a stint on Saskatoon mats, was called upon to spearhead the ambitious undertaking.

Michailoff staged his first card May 4, 1929 at Toronto’s Arena Gardens, with Taylor as the headliner. Attendance numbers were initially low, but as had been the case in Winnipeg in 1922, momentum continued to build. Taylor’s origins as a Bruce County boy helped in building a connection with the local fan base, and his ability to exploit other “home town” connections, such as his father’s one-time residency in Brantford, assisted Michialoff in making inroads into other major centres. A broken leg, incurred in a match with Stanley Stasiak on August 1, kept Taylor out of action for ten weeks, but he returned to the ring to help introduce audiences in Kitchener and London to Michailoff’s new brand of ‘rasslin.

As he had done in Southern Ontario, Taylor returned to his old stomping grounds out west and helped provide Prairie fans throughout the region with their first taste of the “new” professional wrestling, beginning with Joe Zabaw’s Calgary promotion in April 1931. In Edmonton, where Taylor debuted the style in September before a packed house of 1,400 at the New Empire Theatre, they even gave it a name: Australian rules.

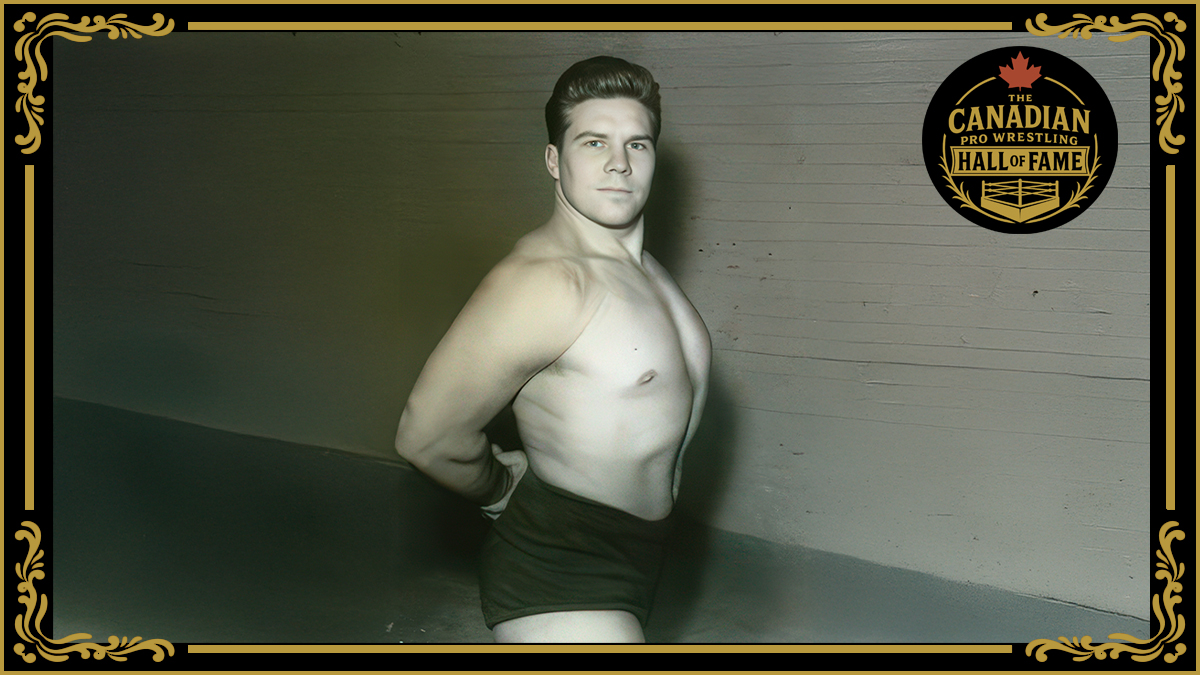

Taylor wrestled throughout the west during 1932 and 1933, but was closing in on the end of his career. Having laid claim to the Canadian heavyweight championship since his salad days before the First World War, and having also claimed the British Empire title for more than a decade, he finally relinquished his laurels in 1933. However, he did so to two individuals: Jack Forsgren and Earl McCready. Although McCready’s win over Taylor has been fairly well documented by Canadian wrestling historians, Forsgren’s victory has not.

Forsgren pinned Taylor’s shoulders to the mat before a mostly-empty house on February 3 in Vancouver in a lacklustre match described as “between athletic flower and fading flame.” On April 21, McCready, the former Canadian national amateur champion, British Empire Games champion, and NCAA heavyweight champion, defeated Taylor before a far more crowded and enthusiastic Calgary crowd at the city’s Victoria Pavilion. To date, a second title change between Forsgren and Taylor, allowing for Taylor to pass the title cleanly to McCready, has not been uncovered. Though he may not have been, technically speaking, a “linear” champion, there is no question that the former amateur standout, who Taylor had also helped groom for the pro ranks, was the most fitting successor to his long-held title. McCready went on to have a long and fruitful career as a pro.

Taylor, who farmed in Alberta during the 1930s, continued to wrestle in the province, donning the tights for the last time in 1939 after a three year layoff. During the subsequent decade he continued to maintain ties to professional wrestling in the province and acted as a referee for matches from time-to-time. Although best known as a wrestler, he occasionally promoted cards. Taylor also helped guide a number of star pupils into the professional ranks. In addition to McCready, he trained Al Mills, Joe Corbett and Pat Meehan.

Former NWA World champion Gene Kiniski knew Taylor when they were both living in Edmonton. “Jack was very, very tough. Jack, he always had a couple of these balls in his hand, or in his pocket. He’d be walking along and he’d be squeezing them. He had a pair of forearms on him like a guy’s thighs. He was a really, really tough wrestler. He could pretty well have handled anybody,” said Kiniski. “He was very, very reserved. In fact, in his latter years he was a bouncer in a gambling club, an illicit gambling club in Edmonton. But he spent his final years in Edmonton.”

During his later years Taylor took employment as a doorman at a night club in Edmonton before a stroke finally robbed him of his fabled strength and vitality. Taylor died at Edmonton’s Royal Alexandra Hospital on May 19, 1956.

In the eyes of western-grown wrestlers that followed in Taylor’s wake, the long-reigning Canadian and British Empire champion held almost hero-like status. Stu Hart considered him a boyhood idol, and undoubtedly his own lifelong passion for submission wrestling, already fading as an art in his own youth, was inspired by Taylor. “Jack was an impressive big man, huge cauliflower alley ears on him and he had a big square face on him and a 20-inch neck, maybe,” Stu Hart recalled to Greg Oliver in 2007.

Bret Hart recalled that his father would frequently talk about Taylor and described him as “the toughest s.o.b. there ever was.”

Indeed, a good case could be made that, in his prime years, Taylor was the toughest Canuck walking the Earth. Learning the art of professional catch-as-catch-can wrestling during a period when legitimate matches could, and did happen, Taylor was a master of the art. After studying under Eklund, he apprenticed with Martin “Farmer” Burns, who had trained Frank Gotch. Like Gotch, Taylor favoured the torturous toehold, though virtually any maneuver in the catch-as-catch-can repertoire seemed to be at his disposal when he called upon it. He was also adept in the art of jiu-jitsu and participated in many matches with the gi. Moreover, he was big. And strong. And fit.

Taylor approached training with an almost religious fervour. He was particularly focused on developing a vice like grip, and used various methods to achieve these ends. In addition to carrying around rubber balls which he would constantly squeeze, one of his training regimes involved tearing yards of cotton to pieces in order to strengthen the wrist and finger tendons. Following that, he would go for a ten-mile run. In the afternoon he would hit the gymnasium for rope skipping, pulley work and medicine ball training, followed by 30 minutes of sparring on the mat. Indicative of his overall athletic abilities and strength, the 200-plus pound Taylor could stand on point like a ballet dancer while wearing wrestling shoes.

Taylor’s reputation as a “trust buster” may have kept him out of the world title hunt for a large portion of his athletic prime, but he carved out an unprecedented legacy in his home country. As Canada’s first truly homegrown heavyweight star, he helped usher in several “booms” throughout his twenty eight year career on the mat. Although most of his early fame was in the west, he led the way in introducing central Canadians to the “new” art of professional wrestling that we recognize today. With his work done in Ontario, he did the same thing in the west. Despite being overshadowed today by several subsequent generations of mat artists, his contributions to Canadian wrestling, sixty years after his death, are both undeniable and profound.