It’s damn hard being Ron Simmons.

“I can’t go to an airport without a little 11-year-old kid running up to me, looking at me asking his mom, ‘That’s the Damn-man right there, isn’t it?'” laughed Simmons.

Well, that “Damn-man” will be at the Montreal Comic Con this weekend and SLAM! Wrestling had the chance to chat with him about his Canadian Football League days, winning the NWA World title, Dusty Rhodes and many other topics.

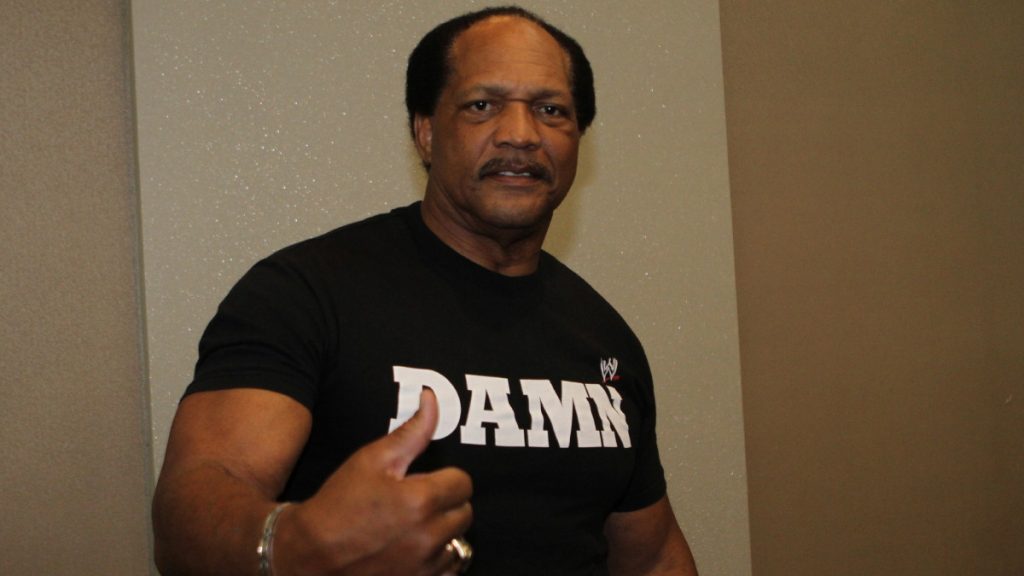

Ron Simmons on Raw in Dallas earlier this year. Photo by Bill Otten, B&B Productions.

The Montreal Comic Con is being held, as usual, in the midst of the CFL season and who better than a former CFL player-turn-pro wrestler to be one of its guests. Ron Simmons and Montreal have a long connection dating back some 30 years, when he used to play in the Canadian Football League.

“I played for the Ottawa Rough Riders for the 1981 and 1982 seasons and was part of the ’81 team that played in the Grey Cup final against the Edmonton Eskimos,” recalled Simmons.

That final was held in Montreal at Olympic Stadium. If it was a sad year for the Alouettes — the team folded at the end of that year — it was the complete opposite for both the Ottawa and Edmonton teams.

“Edmonton was always one of the teams to beat. They had a very good football team,” remembered Simmons about Warren Moon-led Eskimos team that won the Grey Cup.

Ron Simmons at Florida State.

After he finished up college with Florida State University (he’s in the Seminoles Hall of Fame), he was drafted by the Cleveland Browns in the 1981 NFL draft. Although he never played one regular season NFL game, he was able to see the difference between American and Canadian football.

“The width of the football field was much wider in the CFL and being a defensive lineman, I wasn’t accustomed to that. I thought it was going to take me years to get adjusted to that,” he said.

“The other difference was the three downs system, but that I didn’t mind, because if you held them for three downs, you got off the field early, so that was okay with me. But the style of football was basically the same for me,” he added.

Many football players have become professional wrestlers throughout history, the most recent notable recruit being Ring of Honor’s Quinn “Moose” Ojinnaka. Both sports need athleticism, but they have a complete different schedule and for Simmons, that was the big difference between the two.

“In football, you are already accustomed to getting hurt and going to the physical part of it, but the biggest part of getting used to is that in wrestling, and particularly back then, you had to do it almost every day. In football, you have a season and you’re off for three to four months, but in professional wrestling, you have to get use to put your body through that on a daily basis. It took a while to retrain your body to going out there and take a physical abuse like that on a weekly basis. In the long run, at the time I started, yeah, pro wrestling was tougher on your body. Now, not having house shows every day, I believe it’s not as tough.”

Another future pro wrestler was playing in the CFL in 1981. Larry Pfohl, better known as Lex Luger, was with the Montreal Alouettes at the time.

“I did remember him from the CFL, but I only got to know him when we played together with the Tampa Bay Bandits in the USFL in 1983.”

Luger was very important in Simmons’ other career as it was actually Luger who brought him into pro wrestling in Tampa in 1985. Both were trained by the late great Hiro Matsuda, who also trained Hulk Hogan.

Through the ’80s and early ’90s, Simmons’ biggest claim to fame was being an NWA and WCW World tag team champion alongside Butch Reed. But that was before August 2, 1992, when he beat Vader to become the WCW World Heavyweight champion and what many considere the first African-American World champion (although this can be disputed depending on what title you consider as a World title).

For Simmons, now 57, it didn’t make any difference at the time.

“At that particular time, I didn’t even focus on being the first African-American. My only goal was to become World champion. That was the only thing on my mind, to have the opportunity to win that belt. As time went on, I started thinking of the significance of it and it is more than I thought it would be. Even to this day, people tell me the impact it had on their life.”

In his corner for that match was someone that the wrestling world lost just recently, “The American Dream” Dusty Rhodes, who died June 11th. Like so many others, Dream influenced Simmons in many ways.

“I started in Florida Championship Wrestling and he had more of an impact on my career than anyone, but Hiro Matsuda. When I was told about his passing, it was like if time had stopped, I couldn’t believe it. The last time I saw him was during the WrestleMania weekend. He was such a great guy. He always wanted to make sure that you remembered the fundamentals, the basis of what the business was built around. He always told me to never become too big to forget about the people, to always stay in touch with the people. He wasn’t the greatest worker on Earth, but he was so good talking to people.”

After leaving WCW and having a brief stint in ECW, Simmons started in the WWF in 1996 and was given the gimmick of Faarooq Asad, a gladiator, wearing a black and blue outfit, a blue helmet and managed by Sunny. It was a weird gimmick to say the least and it seemed another former NWA/WCW World champion that Vince McMahon was portraying differently, akin to what polka dots were to “The Common Man” Dusty Rhodes in WWF.

“Even to me, it felt weird,” Simmons admitted.

“Weird compare to the All-American football player I used to be. But here’s the thing I learned from Vince. When he questioned your loyalty, when he wants to know about your loyalty and your dedication, like he did with Dusty, he wants to see if you can take something that seemingly nobody can see anything in and turn it into something! When you think of it, it’s brilliant, because you need to work and concentrate hard to get the gimmick across. Look at Dusty, he took polka dots and got it over. For me, with that blue helmet, nobody would have given it a chance. Even I had questions about it. But I told myself I was going to do the best I can with it and sure enough, at some point, it started to twist and got over. It made me a better person and a better worker, I can tell you that,” added the WWE Hall of Famer.

In fact, the Faarooq character became the leader of one of the most remembered stables in the Attitude Era, the Nation of Domination. It is well remembered not only for Simmons, but for being the faction where Dwayne Johnson found himself as The Rock.

Faarooq as leader of the Nation of Domination.

“That’s how he got his identity, Simmons said. They didn’t know what to do with him. I was able to help The Rock get over on the mic, to help him with his personality, with some of his catchphrases. He got a lot of this from me and I was glad to help giving him an identity.”

And like Pat Patterson and Vince McMahon, Simmons knew right off the bat that Johnson would be special.

“It was just a matter of time before he found his niche, his own identity. He had tried to come along and do stuff that his family background was doing. They didn’t want a younger version of High Chief Peter Maivia. They wanted him to find his own identity and being himself. And that’s when he took off. It makes me feel good I had a little to do in this.”

From N.O.D., Simmons became part of the Acolytes Protection Agency (APA), with John Bradshaw, before the latter was known as JBL. To see them playing poker, raising hell, drinking and smoking cigars didn’t seem like working — which Simmons pretty much confirmed.

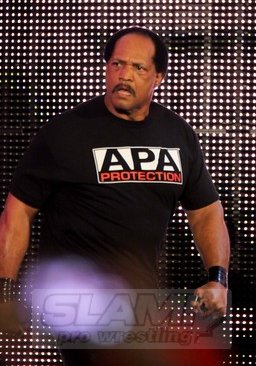

The Acolytes Protection Agency.

“It wasn’t so much that we had to act. We had a similar background and we loved doing that kind of lifestyle outside the ring, it was a natural thing for us to do. We weren’t really working, we were having fun. I couldn’t have asked for a better partner. And we were well paid to do this, drinking beers, smoking cigars. The concept was right, the gimmick was right.”

It’s also during that time that the catchphrase — what am I saying, the word — that is so connected to him, even today, got its roots.

“Let’s just say I’d jump off the top rope and I’d sprain an ankle or I would miss a move or something, and the first thing I’d yell out was ‘Damn!’ and the people in the first few rows could hear me say that. Every time I was coming back to a city, the fans would notice that every time something would go wrong, I would say ‘Damn!’ and as I kept coming back to each of the cities, I noticed that they would all start chanting ‘Damn!’ One day I asked Bradshaw what they were doing.

“I think they’re talking about you,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, every time you do something and it’s not right you say ‘Damn!’ and that’s what they’re saying.”

But the story doesn’t stop here.

“The writers picked up on that too. So we were in Chicago and Booker T and John Cena were doing something and they asked me to just walk on stage and after Cena was done talking just to say ‘Damn!’ and see the response. And it got over with the fans. You never know what people are gonna like, right?”

Along with Road Warrior Animal and Too Cold Scorpio, Simmons will be at the Montreal Comic Con this Friday, Saturday and Sunday. For Simmons, it’s a chance to give back to the fans.

“It was new to me until I started doing some of [the comic cons] and I fell in love with it. I always told myself that after I retired, I wanted to be able to say hello to the people and thank the people for all the wonderful years that they have supported me. My first time in Montreal was in 1981 when I was playing in the CFL and I had such a great time. I just love the city of Montreal and can’t wait to be back.”

Wrestling fans, if you want to go and yell a big “Damn!” at Ron Simmons, the Montreal Comic Con is being held at Le Palais des Congrès in downtown Montreal. For info, visit montrealcomiccon.com.

RON SIMMONS STORIES

- Feb. 17, 2018: Ron Simmons returns to Canada for Legends of Wrestling 2

- June 12, 1997: SLAM! Wrestling chats with Faarooq