“Nature Boy” Buddy Landel, one of the greatest “What If” stories in professional wrestling history, has died. He was 53.

According to The Wrestling Observer Newsletter, Landel was in a car accident on the weekend and went to hospital. He returned home and was found dead by his wife.

In The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels, Landel was asked to examine his legacy.

On the verge of stardom in 1985, he instead retreated into substance abuse.

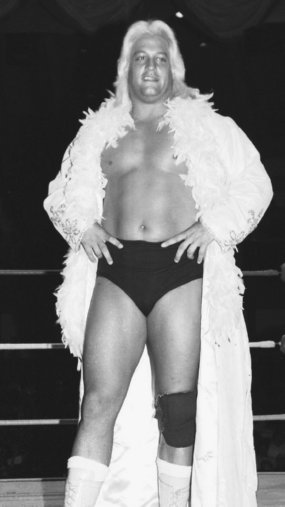

“Nature Boy” Buddy Landel

“If Buddy’s here, if Buddy’s in his right mind, Buddy can draw money as good, or better, than anybody,” said Landel. “But the thing is I was just undependable, and I was unreliable. If I was there and I showed up, you can count that we were going to sell out.”

Born William Ansor on August 14, 1961, he was a fan growing up in Knoxville, Tenn. Nature Boy Buddy Landel (his full legal name now) had a sister who was dating Barry Orton. Knowing Landel’s interest, they’d wrestle a little when Orton was visiting, and soon Landel was introduced to Boris Malenko, who would become his trainer. “I was 17 years, and I was just coming out of high school amateur wrestling. I was in fantastic shape anyway. There were about 30 or 40 guys that tried out, and I was the only one that made it,” said Landel. It was a strange world for Landel. He was living in an apartment with Bob Roop, and in the same complex with Bob Orton Jr. and Archie Gouldie and smart to the business, but Malenko never smartened him up.

He would debut in the middle of the promotional war between the Poffos and the Fullers. He was an insignificant cog in the wheel, a low-level, dark-haired babyface in the background. “All these guys were carrying guns and stuff. They were actually shooting with each other on television. I thought, ‘What have I gotten myself into? Roop’s telling me this thing’s a work, except this part’s real, about them fighting each other. … I didn’t know what the hell to think.” In order to make ends meet, he slept in the store-front window in Randy Savage’s gym in Lexington, Ky.

To get away from the chaos, he went to Bill Watts’ Mid-South promotion. “I knew Buddy before he got in the business in Knoxville. I knew his folks. In fact, when he first went out to Watts, he called himself Buddy Roop,” said Bob Roop. “I liked Buddy. If you think about it, imitation is flattery.” His sister came up with the name “Landel” and he started using that in Memphis. It was also in Memphis that he got the call that would change his life, and allow him to shine.

Tom Renesto Sr. phoned from Puerto Rico, where he was booking, and asked if he’d consider bleaching his hair and come in as a heel. He was quickly thrust into the spotlight, even if he didn’t realize it. “We did six hours of TV in one day, six shows in one day. I really didn’t know what they were doing because I had just been a babyface for two or three years. I was down there with Crazy Luke Graham and Dick Steinborn. I was the hot opening on every show, and I was the close on every show, and running in two or three times. I remember asking Crazy Luke Graham, ‘Do you think they’re giving me a push?’ ‘Hell, kid, Ray Charles can see that.’ I didn’t know.” For eight months, he learned from Renesto, who was formerly half of the famed Assassins team. “When I came back to the States, I don’t know if I can say that I was a seasoned veteran, but I drew money right after that.”

Buddy Landel and Austin Idol at a fan fest in October 2009. Photo by Michael Coons

In Memphis, Jerry Lawler added the “Nature Boy” name to Landel. “What a talent this guy had. Great mouth. He just was naturally a great, great mouth,” said Memphis announcer Lance Russell. “Lawler is amazing at that, and Landel was the same thing. Boy, you get those two guys working a mic and you’ve got a couple of guys that know what they’re doing.”

Landel was then part of the massive exodus from Memphis to Mid-South, where Watts was gearing up for a national run. “That was the school of hard knocks there,” Landel said of the Mid-South territory, with its long trips and hard-nosed boss. “If you ever worked for Bill Watts, you were two things: You were a good worker, or a great worker; and you were tough. Bill Watts didn’t hire anybody who wasn’t actually a tough guy.”

Terry Taylor was a frequent opponent there. “Landel was the type of guy that got real heat, and I mean in the ring and out,” Taylor said. “Buddy was the kind of guy that really, in real life, people didn’t like. He just couldn’t help it. He had this air about him, and he was cocky. If you knew him, you knew it was all a smokescreen and all that stuff, but if you didn’t know him, you wanted to fight him. Everybody did. And he wasn’t tough at all, and everybody knew it. He was the kind of guy that everybody thought they could whip and they wanted to, which is the perfect kind of heel.”

A young Buddy Landel.

By the time he got the call to go to the Mid-Atlantic area in 1985, Landel was one cocky 23-year-old. “I knew I was good, I knew I was with great talent, I knew this was an opportunity of a lifetime, I knew I was in the driver’s seat,” Landel bragged. “I was like an artist out there and my canvas was the wrestling ring. I could make you laugh, I could make you cry, I could make you hate me. I had learned how to pick one person out of the whole coliseum, and jump on that one person and get on them. That one person, by my insults and innuendos, would get the whole place going. I didn’t have to work the whole building.”

J.J. Dillon was assigned as Landel’s manager, and a build was made towards a “Nature Boy” versus “Nature Boy” feud with Ric Flair. The plan was aborted after a length build and a three-month run, though Landel considers the matches the pinnacle of his career. “It never really took off as we had hoped it would,” admitted Dillon. “Part of it, I think, was Buddy having some personal problems and the feeling being that there wasn’t a lot of confidence to invest a lot of television time into something involved Buddy for fear this thing wouldn’t follow through to fruition and fall apart.”

Landel figures he abused drugs for 10-15 years. “There’s something about the adulation of a crowd, either cheering your name or booing you, and then you have the admiration and the adulation of people swarming you and all that. Then you go back to the hotel room, and there’s just nothing,” he said. “I don’t blame anyone or anything, it was just me having an addictive personality. I couldn’t just do a little of nothing, I had to go over the top on everything that I did. I’m kind of a shy person in my family life, and I think that’s the opposite of my personality [in wrestling]. I could live out there in public, and I could live on the stage, a different person than I actually was. I was thinking to myself back then I needed these substances to get my courage up to do these things. The rationale of a 22-year-old guy in there with the world champion selling out every night, unless you put yourself in my shoes, you really can’t, I can’t expect anybody to understand that. I can only try to explain a little bit. I understand now that I didn’t need that.”

By 1986, Landel’s personal demons had driven him out of the spotlight. He’d resurface on occasion: WCW in 1990; USWA in 1993; and most memorably, his last major run, in Jim Cornette’s Smokey Mountain Wrestling, which also led to a brief stint in the WWF in 1995. Landel started the same day as “The Ringmaster” Steve Austin, but slipped a fell during a snowstorm after his third match with the company, and was out six months. “It was just one of those things were success eluded me again as far as wrestling was concerned.”

In The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels, Landel credited his wife, Donna, of 25 years, his two daughters, and his faith for cleaning up his act. “It’s something that I still have to work on today, because I’m wild as a buck, even today.”

RELATED LINK

- June 22, 2015: Buddy Landel’s brief WWF run