Chuck Browning was one of those kids at ringside during the heyday of Cowboy Bob Kelly, who died on Sunday, October 12, 2014, at age 78. He was such a fan that his mother made him up a vest just like Kelly’s. Now 54, he shed a tear learning about his hero’s passing, toasting him and the memories of the days when heroes were heroes.

“We would buy general admin tickets and I’d go sit with a buddy, whose family had front row seats,” Browning recalled, naming the arenas — Fort Whiting, and later at the Mobile Auditorium — with ease. “Matches with and against the Fields, Bobby Shane, Mike Boyette, Ken Lucas, Ken Peterson, Rip Tyler, Briscoes, Funks, Fargo, Rip Tyler, Eddie Sullivan, Medics, Pros, Plowboy, Gorgeous George Jr., Monroes. I’d watch WEAR TV on Saturday night until it went off, and then switch to some station in Mississippi where I got no picture, but could hear the matches.”

That loyalty to the Cowboy continued through the years, mostly because Kelly never forgot who he was and what he meant to people. As the Internet age came along and kayfabe passed away, Kelly was enlivened by being able to share his memories with fans from the past online.

“Fast forward to about 10 years ago. I saw a Gulf Coast thing in Yahoo Groups and there was my idol, Cowboy Bob,” said Browning. “I sent him and email, showering him with stories of his impact on a child, knowing he’d never answer. Imagine my surprise when I got his response. I cried as I read his email thanking me for remembering an old man. My wife thought I had lost my mind, crying over an email from a person I’d never met.”

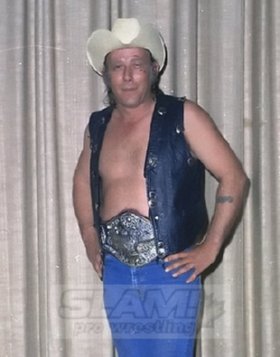

Cowboy Bob Kelly. Courtesy Chris Swisher

Such is the legacy of Cowboy Bob Kelly.

Yet his is a name not really known much beyond his home territory, the Gulf Coast region, from northern Florida into Alabama and Mississippi.

In 2011, following the passing of another Gulf Coast legend, Bobby Fields, Kelly talked about the reasons to stay in one territory for so long.

“It was a deal where we didn’t need to go anywhere else. We had a home there and we was booked and we was on top, we made money, and we were home almost every night of the week — we were only out of town once or twice a week; we were back home every night but once most of the time,” Kelly said. “We wouldn’t have gained anything by going anywhere else. I was happy and he was happy, and what else do you need? He was married 55 years and I’m married 53, so our wives were evidently happy with us. We didn’t have any reason to go anywhere else.”

It’s important that Kelly mentioned his wife, Chris, whom he married in June 1958. Her passing in October 2013 gutted him, and most will concede that he died of a broken heart as much as anything, though lung cancer is the official cause. His family was at his side as he passed.

Robert Raymond Kelley was born on June 28, 1936 on a farm in rural Kentucky. At 5-foot-11, he wasn’t a giant, so it took some convincing before he got to wrestle, even with his credentials from the wrestling team during his stint in the U.S. Marine Corps in the early 1950s. He started out in 1959 in the Louisville, Kentucky, promotion run by Wee Willie Davis setting up the ring and doing some ring announcing; his loyalty led to some refereeing gigs.

Davis and Doug Kinslow were his initial trainers for professional wrestling, but his real lessons came in his first territory away from home, working in northern Ontario for Larry Kasaboski during the summer of 1965.

For the Northland Wrestling promotion, “Irish” Bob Kelly refereed and wrestled, and credited Matt Gilmore, who was best known as Duncan McTavish but was working under a mask as the Hangman at the time, as his mentor.

“I talked to Matt a lot. For some reason, he always liked me. He watched me work my matches a few times. He was trying to tell me stuff. He asked Larry to book me with him in North Bay, so he could work with me and show me what to do,” recalled Kelly in 2006. “Coming back, and doing stuff on your own, he was telling me, ‘You’ve got to do your own shit. You’ve got to do your own thing in there. If you go too far, we’ll stop you. But go on, do what you have to do to get yourself over.’ I’d be starting a comeback, but kind of hesitant. He’d say, ‘Come on, come on, come on! That’s it boy, keep on coming!’ Man, the people were going crazy, and he’d bail out of the ring, and them people just went crazy. I never will forget that feeling that I had. He came back in the ring and said, ‘See, I told you could do it, boy. Just hang in there.’ Every time he would get the chance, he’d have Larry book me with him and I’d work with him. That’s what really got me going.”

While he was working north of the border, he got the call to come into Mobile, Alabama, centre of the Gulf Coast territory. There, Charlie Carr and Lee Fields furthered his wrestling skills.

Kelly fell in love with Mobile — the weather, the people, and most importantly, the Fields family that ran the promotion. Lee Fields became Kelly’s best friend. He often talked about how the two miracles in his life were meeting and marrying his wife, Chris, and making friends with Lee Fields.

And when Lee stopped wrestling, Bobby Fields stepped in. “Him and I just got along. We went over a million miles together in the car. I was him more than I was with my wife,” Kelly said of Bobby Fields. “We never had one minute’s trouble, no arguments at all in all that time. He was just great to be around. Him and I worked as tag team partners so many times. We knew exactly each other’s moves and we worked out routines and things that we could do. It was just a pleasure to be around him in the first place, and to be able to work with him like that, especially Lee’s brother, taking Lee’s place. It was just one of those things, you run into people every now and then that you’re just a natural with, and he was one of them.”

The Fields and Kelly knew the importance of the fans. “Him and I after the matches, we’d never just leave. We stayed around and signed autographs until the people would leave and have enough of it,” he said. “When we would work a match and it was over, even if it wasn’t a main event, say it was a semi or whatever, we would stick around until after the match was over and talk to the fans and answer their questions and sign their autographs.”

With his bulldog finisher and fan adoration propelling him to the top, Kelly held countless titles in the various arms of the Gulf Coast territory, such as Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi, the City of Mobile Heavyweight title. Aside from trips to southern Florida, where Eddie Graham was the promoter, and into Puerto Rico on a couple of occasions, Kelly never needed to travel.

He also was the booker for many years in the Gulf Coast area, keeping himself in shape to strategically re-insert himself into storylines should the need arise. His last match was in 1987, a full decade after his full-time run ended.

When he was breaking into the wrestling business, Kelly also had a fondness for the rodeo, and was a competitive bronco rider. Later, through his association with Lee Fields, who owned the local motor racetrack, Kelly became a race car driver as well. After his wrestling career ended, Kelly ran a wrecker service in Mobile.

Cowboy Bob Kelly and Ronnie Garvin at a Cauliflower Alley Club reunion.

With the racetrack as its base, Kelly was the President of the Gulf Coast Wrestlers Reunion, an annual gathering where past grudges were forgotten at the door, and a member of the Cauliflower Alley Club Board of Directors.

“The wrestling business has given me some awfully good memories and friends. I’m so thankful I spent my time in Mobile,” Kelly said in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons. “I was just blessed. I really did enjoy what I did and what happened to me since then. The wrestling business is responsible for that. People today call me because I’m Cowboy Bob Kelly. It’s still a blessing.”

Bob Kelly’s funeral is Friday, October 17th, 2014, with visitation at 2 p.m. and services at 3 p.m., at Our Lady of Lourdes Church, 1621 Boykin Blvd., Mobile.

He is survived by his children, Mary Lisa Williams, Julie L. Kelley, Michelle Kearsey, and Tim L. Kelley, as well as his brother, Ernest L. Kelley, and sisters, Jeannie Seaborne, and Libby Breeding.

RELATED LINK

- Mat Matters column: Reflections on the Cowboy