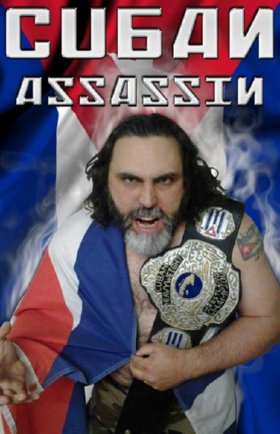

When Richie Acevedo debuted in the Maritimes 25 years ago, it was under a mask, an unsure rookie who wasn’t deserving of his father’s name. Heading back to Eastern Canada this summer, Acevedo is the Cuban Assassin through and through, a suitable heir with suitable hair to one of the most consistently successful gimmicks of all time.

Usually dressed in fatigue pants, black boots, with a scruffy beard and wildly-unkempt hair, both generations of Cuban Assassins have brought mayhem and destruction to the Maritimes.

The original Cuban Assassin is Angel Acevedo, from Puerto Rico actually, who ended up working for promoter/wrestler Emile Dupre when the Montreal Grand Prix Wrestling promotion folded in 1977. Dupre consistently brought “The Cuban” back again and again when he would run his summer tours of the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

There isn’t much that the Cuban Assassin didn’t do in Atlantic Grand Prix Wrestling; he feuded with everyone, often in bloody battles that brought return match after return match to the same towns throughout the summer.

“My Dad was what you call bizarre, one of those wrestlers that stick out like a sore thumb, that made himself noticeable,” said Richie Acevedo. “Not being a very big, tall guy, he made himself noticeable with the wildman look, the hair and the style. Plus my father had a great ring psychology.”

Short and stout like his father, the 5-foot-7, 232-pound Richie was a natural to become Cuban Assassin #2. But it wasn’t an easy start.

“I grew up watching wrestling. My stepfather was a big fan, after my Dad and my Mom separated,” said Richie, who was born in Patterson, New Jersey, on September 13, 1970. His favourite wrestler was Tully Blanchard. “It was a connection between me and my stepdad, we shared that. The thing was, it was never planned for me to be a wrestler. I never said I wanted to be a wrestler. I always loved it and thought I might be able to do it one day. I was going to be an airline pilot originally or a cartoonist.”

In the summer of 1989, the Cuban Assassin flew his son up from West Virginia, after graduating from high school. The idea was to spend the summer, father and son, while Angel worked for Dupre once again. Divorced from Richie’s mother, Yvonne, for close to a decade, it was a chance to spend time with his son.

The Cuban was sharing an apartment with a motley bunch — Gerry Morrow and Frenchy Martin were on the main floor with the Acevedos, and upstairs were Pat Brady and Eddie Watts and Buddy Wayne Gillis.

Though his role with the wrestling promotion was still to be determined, Richie had a job in the apartment.

“My Dad would be the cook, do the grocery shopping. Gerry Morrow washed the clothes. My job was to straighten out the apartment and wash dishes. Best as I can recall, Frenchy Martin’s job was going out and having a good time with all the ladies — but what a great guy.”

Richie was a bodybuilder in high school, but only 180-190 pounds — “a mean, cut guy, but not big.” He had some photos done up that he sent ahead to his father. What he didn’t know is that the Cuban had given the photos to Dupre, who was intrigued by his physique and saw potential for a new wrestler.

But Richie didn’t know that Dupre loved the photos until later. Instead, Dupre approached the youngster, and asked, “When can you start?”

“I’m thinking it’s putting up and taking down the ring, simple things, whatever needed to be done around for the show,” recalled Richie. “I said, ‘I can start any time.’ The boys started laughing in the locker room. I didn’t know, because I wasn’t smart to the business at that time. Emile said, ‘Okay, you start tomorrow.’ Then he walks out.”

It was up to Angel to explain what was what: “My Dad says, ‘Richie, when he said “work” he didn’t mean manual labour work, he meant work as a wrestler in the ring.’ That was the first time I’d ever heard the wrestling terminology of wrestlers being called workers. I said, ‘Oh Lord, what do I do?’ He said, ‘It’s too late. Everyone saw you have a verbal agreement with him.’ Dad started training me in the basement apartment — which wasn’t fun. Then he would train me inside the ring when it was set up.”

There were other mentors around too, including Phil Lafleur (Phil Lafon), Leo Burke, and Ron Starr.

“My Dad didn’t take it easy on me,” said Richie. “He just trained me to take the bumps and falls, simple, basic things.”

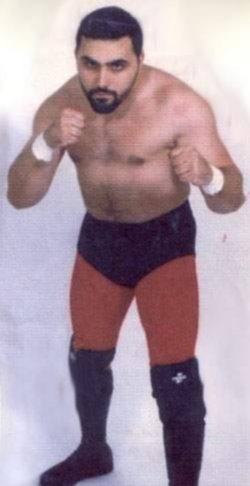

A spitting image of his father in 2000 in Stampede.

And when it was time for the rookie’s debut, which was in Montague, PEI against Eddie Watts, the Cuban Assassin didn’t really offer up much last-minute advice.

“When I went out the door, my Dad says to me, ‘Okay, this is the big leagues, major leagues. You’re on your own. I’m not going to watch.’ When I was going out the door, everyone was patting me on the back, ‘Good luck, good luck, good luck.’ I’m wondering what all this is about. I go out, and they have me under a mask as a Super Bee — I was one of the Super Bees when I started. Everybody was pulling and tugging me. I didn’t know there was a couple of guys that were there before as the Super Bees the year before, I had no clue.”

Having survived the abuse of the fans on the way to the ring, Super Bee found himself across the ring from Watts, listening to the referee’s instructions.

“Eddie Watts just looks at me — I’d met him at the apartment, nice, friendly guy — but all of a sudden in the ring, it’s like a totally different person. This guy was like the devil, sadistic and evil and kind of reminded me of Kevin Sullivan a lot. He just looked at me and said, ‘I don’t care who your Dad is, I’m not going to be easy.’ I looked at the ref and said, ‘What does he mean by that?’ He said, ‘I don’t know.’ They ring the bell and we go to lock up, and he gives me the stiffest knee in my gut, knocked the breath out of me like you would not believe. He just pounded me for 20 minutes in that match. Literally, I got beat up for 20 minutes, not knowing what I was supposed to be doing.”

Circa 1986.

During the bout, Richie caught sight of Ron Starr standing nearby, watching the match, arms crossed, shaking his head. Starr was able to encourage Richie to fight back. “I guess he felt sorry, seeing me get beat up,” he chuckled. “I’m terrified, 18 years old, and this guy is beating the crap out of me.”

The subsequent 25 years of matches have gone considerably smoother. The second Cuban Assassin — or is it third? Depends if you count the “other” Cuban Assassin, David Sierra from Florida — worked in Puerto Rico, did a bunch of tours of the Maritimes, and worked around his West Virginia home. There were times he was very busy during his career, and other times when he wasn’t.

The resurrection of Stampede Wrestling in 2000 was a career highlight, and he only got booked on a fluke.

Richie was trying to get a hold of his father, and the phone number he had for him wasn’t working, so he called Ross Hart.

“Ross called me back and offered me a spot on the tour, so I took it. I couldn’t say no,” chuckled Acevedo, who was known as Satanicus in Stampede, a red devil outfit inspired by his high school mascot with the Oak Hill Red Devils. Satanicus got to wrestle against his dad and also tag with him. He loved the international flavour of the talent roster, and especially remembers his matches with Wavell Starr and Red Thunder.

“Richie has an old school mentality and he and I really clicked in the sense that we appreciate the same style of work,” said Wavell Starr. “I respect all styles but I prefer the old school southern style — Louisville and Memphis walk and talk. We would have some stuff planned out but for the most part would feel our way through the match by reading the crowd. There are not a lot of guys these days with the talent to be able to do that.”

Through the years, Acevedo has supplemented wrestling income with work as a professional driver, piloting everything from buses to taxis to emergency vehicles.

At the urging of good friend Robert Maillet — Kurrgan in WWE — he is giving acting a real shot as well, and has a couple of roles under his belt (MILFs versus Zombies, Bounty Hunter War), with a few more to follow after the summer wrestling tour.

The realization that maybe wrestling wouldn’t last forever came in 2006. He was on a summer tour of the Maritimes, and came home to West Virginia during a break in the tour. It also marked the breaking point of his marriage.

Richie Acevedo, zombie.

He tried to salvage the relationship, quitting the tour, getting a job at a movie theatre, and doing the unthinkable — shaving.

“I kind of blamed [the divorce] on the wrestling and the character, so every time I looked in the mirror, I looked at myself with disgust and blamed myself for it,” he said. “So I just shaved my beard and shaved my hair and didn’t go back for the second half of the 2006 tour.”

While the hair grew back, the marriage didn’t. But that other mistress of professional wrestling was still there, and he slowed down in 2010, and figured he had his last match. But hey, things change. “My last match didn’t go the way it was supposed to, it wasn’t the kind of finish I wanted.”

Come 2012, and Acevedo is working with a West Virginia promotion, helping to mentor wrestlers. Keeping up is an issue: “I don’t really like the young guys slowing down their pace to me; I’d rather speed my pace up to them, because that gives you the better performance.”

He got a feature position, taking part in the first-ever boxer versus wrestler match in West Virginia, against Justin “No Mercy” Robertson, in February 2012.

“A lot of people don’t realize how real that match really was. I had bruised ribs for about two weeks, a slight concussion for about six days,” he said. “I took about eight months off just to take a break from it. I really was planning on retiring and calling it my last match, and then a local promotion called me and wanted me to work with some young talent.”

It’s a challenge dealing with some of today’s wrestlers, he said, as they think they know it all far too early in their careers, but he respects their desire to follow their dreams.

He is proud of what he’s done, and is hoping to have a DVD of his career put together later this year or next. “Wrestling is an art form, it’s a performance art of athletics mixed with entertaining, hence the term sports entertainment, which is exactly what it is.”

Now 43 years old, the Cuban Assassin (#2!) has a chance to keep his own dream alive, and is looking forward to the great weather, short trips and good times that mean a summer tour in Atlantic Grand Prix Wrestling. “It is coming home, because the Maritimes is my second home in the whole entire world,” he said.

And there’s another second-generation wrestler in his sights, René Dupre, who has become a star in Japan, and comes home in the summer to run the territory that his father, Emile, made famous.

“The thing I really like about René, there’s two things: he’s keeping the Atlantic Grand Prix Wrestling tradition, but he’s also putting a touch of what he already experienced when he was in the WWE, Japan, and all his world travels, including England,” said Acevedo. “He’s bringing all that in, a nice, good mixture there, and he’s bringing it into the Maritimes. So it’s the traditional Grand Prix Wrestling but with a little spice added to it.”

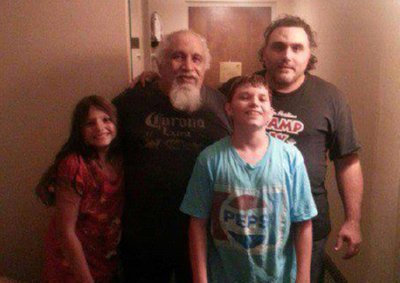

A father-son tag team from 1999.

The second Cuban Assassin has a history with René Dupre, just as his father had a history with Emile Dupre. The younger Dupre was just 15 years old, wrestling as René Rougeau, when Richie Acevedo first got to wrestle with him in 1999.

“They brought me in to work with him, polish him up. … To me, René already had everything there, it’s like an artist carving clay to make a sculpture; the sculpture is already there and all I did was cut off the rough edges,” recalled Acevedo. “He was already packaged to become what he was going to become. He had it in his mind, he had it in his heart, he just had the drive for it and the passion for it — so he was going to go regardless if it was me or anyone else.”

René Dupre shared his thoughts on the legacy of the Cuban Assassins in Eastern Canada: “He’s continuing his father’s legacy going on near 50 years in the Maritimes. He and my father had many memorable match-ups and this year the feud continues.”

Three generations of Acevedos.

With the end of his wrestling days not far away, Richie Acevedo has been thinking about how he might handle things if his own two kids, Quinton, who is 14, and Madison, who is 11, decided to follow in the footsteps of their father and grandfather.

“If my son or daughter wanted to get into the business, I would definitely go out of my way, probably more beyond what my father did for me — and I don’t mean any disrespect for my Dad. My Dad’s old-fashioned,” said Richie, adding that he’d probably call up George South to do their training, and make sure that they got a chance to wrestle in many different locations like he did.

ATLANTIC GRAND PRIX 2014 TOUR

July 23 – Baie St. Anne, NB

24 – Neguac, NB

25 – Black Harbour, NB

26 – O’Leary, PEI

27 – Borden, PEI

28 – Souris, PEI

29 – Minto, NB

30 – Centre 200, Sydney, NS

31 – Baddeck, NS

Aug. 1 – Truro, NS

2 – Berwick, NS

3 – Springhill, NS

4 – J.K.Irving Centre Bouctouche, NB

5 – Lamèque Arena, Lamèque, NB

RELATED LINKS

- June 16, 2020: Richie Acevedo plays an Assassin (of sorts) in horror film ‘WrestleMassacre’

- Jan. 27, 1999: Cuban Assassin wild in the ring, nice outside it