If the measure of a man and the impact of his life on others can be measured by how many people want to talk about him when he’s gone, then Johnny Canuck, a veteran of the rings of British Columbia, was an elite superstar. The phone didn’t stop ringing with colleagues wanting to praise the man who died of a heart attack on Thursday.

Before getting into Johnny Canuck, it’s first important to get to know John Collins a little.

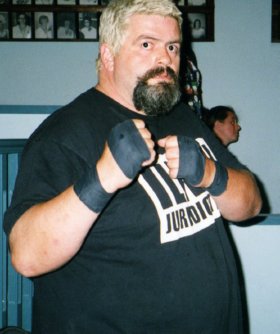

Johnny Canuck. Photo courtesy Brad Rees

He was born October 21, 1957, in Verdun, Quebec, the son of Gerald Collins, a boxer who represented Canada at the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, competing in the Light-Heavyweight division; he was also Montreal Golden Gloves Champion and a boxing coach. There were five children in the Collins family.

John Collins grew into a big man, who loved life and was loved. He had six children through the years, with various partners, living up to the later “Loverboy” nickname.

Much of his identity was tied up in his work as a longshoreman on the docks of Vancouver, and he took great pride in his job and his union.

“The docks, longshoremen, are one of those places where it’s who you know,” said John Partlett, later known as wrestling personality Terry Joe Silverspoon. Collins would encourage and help friends and other wrestlers find work on the docks, including Mark Vellios — wrestler Michelle Starr — and Nathan Burke, who works as Disco Fury.

“He was also a strong union man,” said Burke on Friday, sharing a photo of the Canadian flag at half-mast on the docks as a tribute. “I was going to take the day off today, but he wouldn’t want me to do that. ‘Got to protect our jobs!'”

Like Burke, Vellios went to work despite the pain of losing one of his best friends.

“As I worked last night on the docks all I could think about was the passing of my friend, coworker and tag team partner, Loverboy Johnny Canuck,” wrote Vellios on his Facebook page. “I had to fight back the tears most of the night especially when I read another post by someone else or if somebody stopped to ask me about what happened. ”

And Vellios knew John Collins better than anyone else, and their wrestling lives are intertwined from day one.

Vellios was a child of California, who had learned the wrestling business at a young age, and learned from some of the cagey veterans. Life and wrestling took him up to British Columbia, where he settled and raised a family.

Michelle Starr and Johnny Canuck.

In 1991, he threw open the proverbial doors to a wrestling school — actually a ring in his backyard — to train wannabes. John Collins was his first student.

“He was the first person I ever trained and we remained friends till the end,” wrote Vellios. “We traveled countless hours and miles on the road and have slept in tents, trucks and many sleezy motels. He was a huge part of the local wrestling scene. His very first match at Bridgeview Hall in Surrey was a 550 paid sellout for WCCW. He was the biggest local wrestling drawing card ever without TV exposure.”

Thereasa Hall was another of Starr’s first students, and only just recently hung up her tights after working for years as Raven Lake; she is confident that her daughter, Bambi Hall, can carry on in her stead.

Alternating between tears and laughter, Thereasa Hall remembered training with John Collins, who was ahead of her by a few months.

“Back then, he was a big, burly guy, heavy heavy guy,” began Hall. “One time we were doing a tackle, drop down drill. Johnny being the size he was couldn’t get up quite as fast as everybody else. He’d just roll across and let everybody just jump over him.

“There was one time we were doing headlock takeovers, and we were doing the ones where you run up the turnbuckle, you flip off and do the headlock takeover. Johnny was a big boy and I wasn’t very big at the time. Johnny used to sweat — my God, he used to sweat so bad. I got up there and ran up the turnbuckles and went to flip him over and my hand slipped off of his head. So of course, I go tumbling down, and here comes all 300 pounds of Johnny Canuck, splat, right on my face. For a week, the whole side of my face was all blue.”

Johnny Canuck and Raven Lake.

But he was a teddy bear, said Hall, a good father who had a way with children. “When I first started, I had Bambi and she was just a baby. There were times I didn’t have a babysitter, so I’d have to bring her with me and she’d be in her car seat and I’d have her in the dressing room. If I had to go out to the dressing room and she was awake, Johnny was always the one who, if she would cry, he’d pick her up, he’d bounce her, comfort her. He was just a really, really good guy.”

The 1990s saw a national resurgence of professional wrestling and British Columbia experienced seismic shifts too. West Coast Championship Wrestling and All-Star Wrestling had been around for a while, but Starr saw where wrestling was headed and established Extreme Canadian Championship Wrestling in 1996, a violent, West Coast version of the hardcore ECW promotion.

It was never a question of loyalty with Johnny Canuck, who followed “Coach” as he called Starr.

“For the next 10 years he once again proved to be the biggest draw in company history,” wrote Starr, “When he came to the ring at the Eagles Hall in New Westminster whether he was a good guy or a bad guy the fans loved him or loved to hate him.”

Johnny Canuck, man of the people.

There were two Johnny Canuck personalities. One was “Lumberjack” Johnny Canuck, a babyface that the fans adored; the other was “Loverboy” Johnny Canuck, the hated partner to Michelle Starr.

The third Muskateer for many of the years was John Partlett, who helped set up the ring, did ring announcing, worked on publicity, and later was a manager.

“Starr had a rickety old moving van. The ring stuck out the back of it about six feet,” recalled Partlett. “Starr would drive and Johnny would be sitting up front, and he’d be drinking beer and passing out. Starr would be nodding off at the wheel of the truck. We’d all be huddled up in the back of this cube van hoping to hell that it wasn’t going to crash into a mountain! It was pretty wild and crazy.”

“We put a lot of miles on in the early ’90s,” he continued. “We just flew by the seat of our pants. One day we were in this town, the next day we were in that town.”

Gary “The King” Allen was a referee for many, many years in British Columbia, and put in his time in the van. There was one trip to the northern end of Vancouver Island, and everyone was asleep in the van, except for Allen at the wheel and Canuck riding shotgun.

“And what are we doing? We’re singing The Flintstones song, then we started out with the Gilligan’s Island song. He was trying to keep me awake, right?” laughed Allen. “Next thing I know, I look over and the son-of-a-gun is sleeping!”

The singing wasn’t confined to the cars, either.

B.C. wrestler Azeem The Dream said that at the first show he ever attended as a fan, Lumberjack Johnny Canuck led the fans in singing “Oh Canada.” Later, Azeem recalled being encouraged by Canuck to follow his wrestling dream: “I remember the talk, ‘I’m proud of you. From the fans, to back here with the boys, enjoy the ride, kid.’ I was like, ‘Right on, man.’ It meant a lot to me.”

Canuck didn’t go out of his way to help younger talent said many of the interviewees, though he’d help if asked. Usually he directed people to Starr, said Burke. “If someone had a question, he would answer, but he called Starr ‘Coach,’ and he’d always say, ‘Hey, refer to Coach,’ because Mark’s the one that taught him how to do everything,” said Burke. “If someone was wanting to ask him a question, he’d be right there to answer it — and then he’d sing you a song. It was great.”

“Tornado” Tony Kozina was one of those youngsters on the ECCW cards, a 5-foot-6, 180-pound dynamo who was often a junior heavyweight champion. He had a hard time getting a grasp on Canuck early on, as “he was always in a fun mood” but was legit tough too: “He was an enforcer. If you got out of line, he could legit kick everyone’s ass.”

At 6-foot-3, 300+ pounds, Canuck dwarfed Kozina. But he knew how to tell stories.

“The big feud at the time was Dave Republic and ‘Tradition Rules’ and the NWA stuff,” said Kozina. “I was the Junior champ at the time, so I was on Republic’s side against Starr and Canuck and Team Extreme. Any time there was an eight-man, or a tag match, I’d end up there with Canuck. He’d bounce around the ring selling for me — and I’m half his size!”

Dave Teixeira — a.k.a. Dave Republic — can only look back on awe at what Canuck meant to the ECCW promotion, which Republic sold four years ago, and is still going strong.

“Lumberjack” Johnny Canuck.

“Johnny Canuck was very much the heart and soul of ECCW in the late ’90s, that’s for sure. He was just so over with the fans, so over with the boys in the dressing room,” said Republic. “He had charisma galore. He could cut a promo that was often eloquent but sometimes made no sense — but the crowd just ate it up. He was a brawler. He was the perfect brawler for the late ’90s, the extreme years, if you will. He just encapsulated that — a fat, overweight, every man, that’s what Johnny Canuck was. He started off being Lumberjack Johnny Canuck, the hero to all of B.C., and then he morphed into Loverboy Johnny Canuck, one half of a gimmick gay tag team. Whether he was Johnny Canuck, the lumberjack, or the gay lover to Michelle Starr, he was just so over. It was amazing to see that kind of charisma. He was very easy to work with from an owner and booker perspective. I don’t think he ever said no to anything, at least that I asked him to do.”

There were two aspects to Canuck’s “extremeness” — the violence, which included cage matches, thumbtack matches, tables breaking, barb wire, but also the marijuana.

“He really encapsulated the spirit of extreme, he really understood what it meant,” said Teixeira.

“He obviously wasn’t the greatest technical wrestler on the planet, but he had the charisma,” said Moondog Manson, known as Murray Cairns to his family. “Back in those days when Steve Austin was coming to the ring with a beer, Johnny was coming to the ring with a joint. It was a totally different era.”

Filmmaker, writer, personality Marty Goldstein walked into the world of ECCW in 1999, and had never heard of Johnny Canuck. “When I met John I told him that, and he replied, ‘If you smoked more pot you would have!'” said Goldstein. “A few months later, [Canuck] had them roaring with approval when he came out smoking a HUGE joint — which I was quite astonished by his doing but this WAS Vancouver after all — with a duffel bag but instead of the title belt he was holding hostage inside it, Johnny proudly announced had ‘traded it for all this weed.’ Insane pop. For a guy who had never been on TV it was astonishing how into his persona the ECCW audience was. The closest thing they had to The Crusher. You had to see it to believe it.”

A big key to Canuck’s success was the support of his brothers in the union — the International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 502.

“Loverboy” Johnny Canuck and “Gorgeous” Michelle Starr.

“From the late ’90s to the early 2000s, he was pretty consistent with us, so we would have different shows, and certainly the longshoremen from 502 — he would chant that, ‘502! 502!’ — they were rowdy. They were there to have a good time,” said Teixeira. “They were infectious. You get people in the front row rowdy, the people in the third row get rowdy, the people in the seventh row get rowdy. It was wonderful to have that.”

Like Starr, “Diamond” Tim Flowers is a veteran of the wrestling wars, the two personalities at war themselves for over 20 years now. But Flowers respected what Canuck brought to the table: “Starr pushed him hard because he sold those tickets, man. He was in the main matches, and when there was something going on with him, he sold those tickets down on the docks and the joint was packed.”

“John basically had the same rapport at work on the docks as he did with wrestling. Everybody liked him,” said Partlett. “He was a hard guy to dislike. You didn’t want to be on the bad side of him, let me tell you! If you rubbed him the wrong way, he was the kind of guy that would knock you the f— out. But not too many people were on his bad side. He basically loved everyone.”

The hard-living dockworkers loved his realness, and Canuck could make those punches real, said Cairns. “His father taught him how to be a boxer, and a really good boxer. I remember getting jabbed in the chin by Johnny one time. It didn’t look like much, but that might have been the hardest punch I’ve ever taken. Just a quick jab to the jaw and I couldn’t believe it.”

Burke echoed Cairns’ thoughts. “When he came to the ring doing his thing, people saw this big, burly man, and they were like, ‘Whoa, he’s a massive guy.’ He just demanded attention. It was like, ‘This is real, what’s happening.’ When he hit you, it was amazing. He’d punch and you’d actually leave your feet when you got hit in the gut.”

Johnny Canuck punches Michelle Starr.

But Johnny Canuck, the name itself a tribute to the common man, connected with everybody.

“Even when he was a heel and he would walk out, the fans would still want to go up and shake his hand,” said Allen. “The fans loved the man. The charisma he had was just unreal.”

Vern May brought his Vance Nevada personality to British Columbia near the end of Johnny Canuck’s run, and wrestled him a few times.

“He was one of the biggest babyfaces in the post-Al Tomko era, just over with everybody. Even as a heel, he had a hard time getting the response that he needed because he just was so loved. He just had that personality that showed through no matter what,” said May. “There were a few matches that he did right at the end of his career, and I was in two of them. In 2006, we were in a 10th anniversary ECCW show, with Michelle Starr, Johnny Canuck and myself in a six-man tag. Later on in the year, Starr said, ‘Johnny, you’re too over. We can’t have you as a heel.’ Johnny was really upset with that because he just desperately wanted to be a heel but he just couldn’t. People loved him.”

That extended outside the ring too, said Allen. “Johnny and I and Debbie Nichol, we used to go out on many, many poster trips around the lower mainland, hanging up posters. John was really big that way, because he was a big man and had a larger than life personality. He would walk into a place and ask to hang a poster and people would immediately like him. He’d do the Johnny Canuck thing.”

Indeed, more than one person said that John Collins and Johnny Canuck were one and the same.

All smiles.

“He wasn’t just Johnny Canuck in the ring,” explained Cairns. “He was Johnny Canuck on the docks. He was Johnny Canuck in the bars. He was Johnny Canuck everywhere he went, and he was just known like that. There were people who didn’t even watch wrestling who knew who Johnny Canuck was. That was just it — he was Johnny Canuck 24 hours a day.”

Health was a determining factor in the conclusion of his career. A diabetic, he would later lose a couple of toes to the ravages of the disease. But it was the death of his wife in September 2006, killed by a blood infection that surfaced shortly after a liver transplant, that lead to his retirement match.

“He called it quits and managed to stay away. I’d bump into him once in a while and we’d talk it up,” said Cairns, explaining that “it’s just really hard to be there and not be in the action” so that is part of the reason that Canuck didn’t come out to the matches.

Having started wrestling when he was older, and with a good job and family, there was never any real desire for Collins to head abroad and wrestle, said Hall. “I think he was happy here. He loved the indies, he loved the fans around the indies. Just to be able to do what he did here was good.”

That jibes well with what Collins told SLAM! Wrestling’s Fred Johns in 2006 when asked how he wanted to be remembered: “As a guy that had a lot of fun. I never had a big head or anything — wrestling was lots of fun and I’d like to be remembered as a guy who entertained them. I had a kid throw a Pepsi can as hard as he could at my head, I’ve had people spit at me, I’ve had people cry, I had people cheer me — I want to be remembered as the guy that got the point across.”

Mission accomplished.

Funeral arrangements for John Collins / Johnny Canuck are not known at this time.

RELATED LINK

- July 23, 2014: Guest column: The rib that shrunk Johnny Canuck

- November 23, 2006: Johnny Canuck: Back for G.O.D. and Honky Tonk

- Facebook tribute page to Johnny Canuck

- Archived Johnny Canuck page from 1998