While Al Oeming is quite rightly remembered as a conservationist and nature lover in Edmonton, it was his days as a professional wrestler and promoter that helped him get to that point.

In an interview in October 2011, the contemporary and friend of Stu Hart shared many of his memories from his days in wrestling.

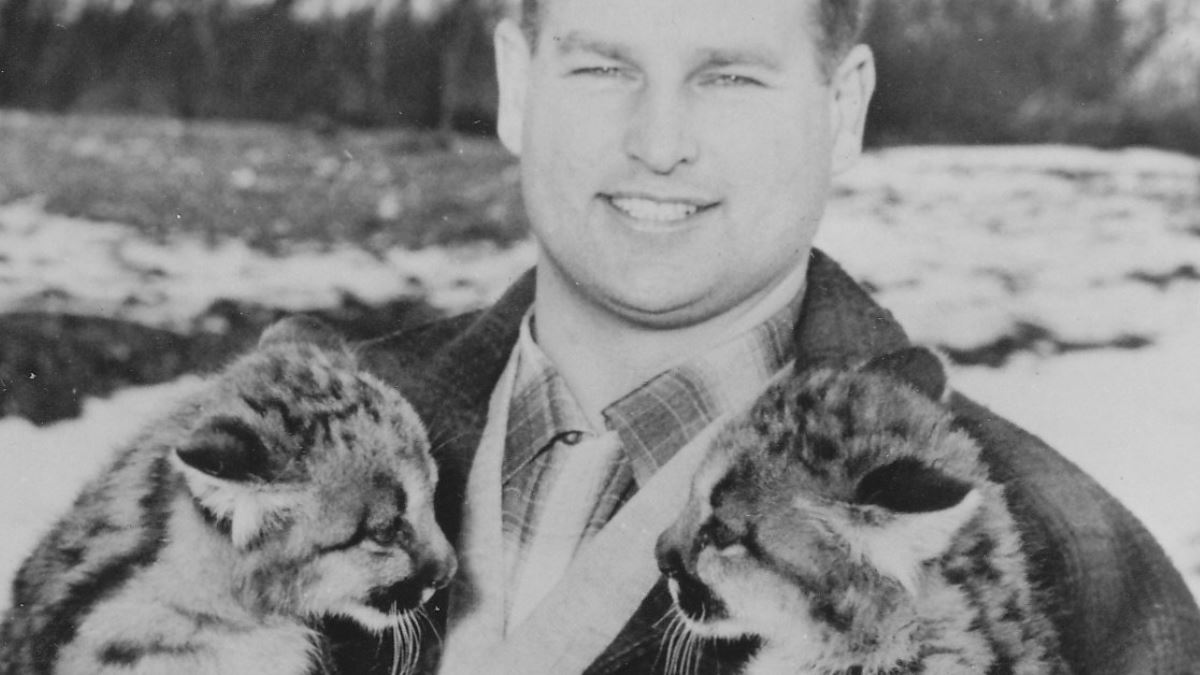

A young Al Oeming on his farm circa 1960.

He was born on April 9, 1925 in Edmonton to Albert and Elspeth Oeming, who had immigrated to Canada from Germany. In 1943, he joined the Canadian Navy and served as a gunner in the South Pacific on board Canadian Naval ships Nonsuch, Cornwallis and Stadacona. In February 1946, he was discharged.

It was his childhood friend Stu Hart, who also served in the Navy, that suggested he try professional wrestling. Hart was wrestling out of New York City, and invited Oeming to come out too. Oeming had a little experience from his time with the Varsity Amateur Wrestling Club.

By 1948, Oeming was back in Edmonton and starting his post-secondary education: ornithology at the University of Alberta. He also played football at university, as a guard.

Hart was in the process of launching Wildcat Wrestling, the precursor to Stampede Wrestling, and sought out his friend to help promote the Alberta capital, a couple of hours north of Hart’s Calgary base.

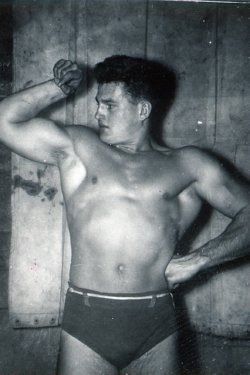

For a time, Oeming — “The Boy Promoter” — also wrestled, with the nickname “Nature Boy” meaning something different given his studies than the ascendant star Buddy Rogers. A May 1954 article in Wrestling As You Like It, in the Canadian notes column by Barry Lloyd Penhale, described Oeming: “Standing just under six feet, the handsome blond weighs around 230 pounds and has a magnificent physique. Oeming and Winnipeg wrestler George Gordienko look very much alike, more so physically than facially. They both train diligently and the result is two of the finest builds in wrestling. Actually, when it comes to muscular development, good-looking Oeming takes a back seat to no one.”

Al Oeming in 1949. Photo courtesy Oeming family.

“We opened here in 1948. See, wrestling had died an agonizing death in this city,” Oeming remembered in 2011. “It died because of poor promotion, lousy calibre of performers. At one time, in the ’30s and ’40s, this was a hotbed for the middleweights. They used to come to town two or three days early. I’m thinking of names like Otis Klingman, Clem Klusick, King Kong Clayton, Sailor Thomas, Lord Lansdowne, Bad Bob Clemings. They were terrific performers. And of all things, the York Hotel was in one of the uglier sections of the city, the dregs of humanity went there. But they had a hell of a nice setup for the wrestlers in there, a ring and everything. … Wrestling was a hot item then. The promoter at that time was Mike Cutler, and that was followed by a fellow named Tommy Tasker. Tasker was a skinflint and spent nothing, and the good guys didn’t come back. He wound up with nobody attending. It went into a state of dormancy, and was dead for all time. So Stu Hart and I, we decided we could resurrect this thing.”

Just starting out, Hart was not the Western icon he would later become. He booked his talent out of Great Falls, Montana, which was run by Gerry Meeker.

Oeming was determined to promote and go to school. (He also married May Dorothy Dennistoun in 1950.)

“Stu didn’t want to do the actual promoting, and I wanted to stay in college, but I said I’d have ample time to promote,” he said. “I got along well with the guys, because wrestlers become believers if you can perform, if you can promote full houses. They didn’t go for bullshit, and talking about, ‘I’m going to do this, I’m going to do that.’ I really worked hard at it. ”

Al Oeming in the 1955-56 Parkhurst card set.

It was rough going in Edmonton, with low attendance, as things got off the ground.

But chaos has a way of selling tickets, and chaos reigned when it rained bottles one night.

The soft drinks were served in bottles instead of paper cups, and during a “torrid” match between Pat McGill (“the best babyface we ever had”) and Al “Mr. Murder” Mills (“the prize villain of all-time”) the fans rioted.

“It rained glass bottles for half an hour,” recalled Oeming. “The timekeeper was the ex-chief of police, and he was banging the gong. Finally the riot squad, the cops, had to come in. It made headlines in the local paper, the Edmonton Journal. (laugh) ‘Riot squad called out as wrestling fandom go berserk.'”

A public inquiry increased publicity, but wrestling got the go-ahead to continue running shows, as long as the drink delivery system changed.

“The concessionaire was told he had to sell his drinks in paper cups,” said Oeming. “Next week, sold out in one hour, and the sellouts went non-stop for 11 years.”

Hard to believe that a wrestling promoter would stretch the truth at all, but Oeming is exaggerating a bit.

According to Bob Leonard, Stampede Wrestling historian, photographer, and later promoter in Saskatchewan, sellouts in Edmonton were not quite as rosy as Oeming portrayed. “But it was a good solid town,” said Leonard. “No idea what Edmonton Gardens held sold out, but biggest gate I can find in my records is 8,000, June 25, 1957, Whipper Billy Watson vs Gene Kiniski. Next best are Lou Thesz vs Kiniski, Watson vs Dick Hutton, Kangaroos and girls, July 10, 1957, 7,000; then 6,500 for Yukon Eric vs Tiny Mills, May 5, 1953. My records are pretty incomplete, though.”

Al Oeming at Mosquito Lake in 1957. Photo courtesy Oeming family.

The big shows were at the Edmonton Gardens, while the regular weekly shows were at the Sales Pavilion, a smaller venue with around 3,000 seats. Leonard described it as a “dirty old joint even in the ’60s when I was first up there; the quintessential grubby, smoke-filled arena.”

Oeming was well aware of the ethnic makeup of the city, with a huge Ukrainian population, but also Japanese, Chinese, and a solid Native Canadian base. “If you had an ethnic group to back you up, pretty soon the building wasn’t big enough,” he said. It was a cross-section of fans too, from the average working Joe to lawyers, surgeons, and actors.

Much of his success Oeming credits to working well with the media, “being faithful,” writing good press releases and always calling in the results.

“The Boy Promoter” had a story on everyone, including The Boy Promoter.

Stu Hart and Al Oeming circa 1998. Photo courtesy Oeming family.

Mike Mazurki was a solid wrestler who had gotten into the movie business. His ability to cross-promote when wrestling meant extra publicity. “I took Mazurki around to the various stations and they all recognized him, been fans of his, watched him in recent films,” recalled Oeming. “Mazurki said to me, ‘Is there any actress in Hollywood that appeals to you? You’re not married, are you?’ I said no. Well, I said, ‘One that I really like is Paulette Goddard.’ ‘Oh, I see.’ Little did I know he was doing a picture with her. So I get this lovely 8×10 picture of Paulette Goddard in an extremely short skirt and frilly outfit. It said, ‘To Al, the Boy Promoter.’ That moniker stuck, you know. The media took it on, ‘The Boy Promoter.'”

Long before there was an NHL hockey team, football’s Edmonton Eskimos meant everything in the town. There were often tie-ins between the team and the wrestling, including a couple of notable names that would later make the switch: Gene Kiniski, Joe Blanchard and Wilbur Snyder.

“The coach at the time was a Torontonian, Annis Stukus, and he was a great wrestling fan,” said Oeming. “He thought it was great, ‘The more extra money they make, the more exposure they can get, I like that.'”

Besides Edmonton, Hart would often ask Oeming to run other towns. He had stories on them all. Here’s one about Hythe, Alberta. There was a rodeo in town, and wrestling was on the bill during the second night.

“The promoter was, of all things, the local undertaker,” recalled Oeming. The arena had 2,000-plus people, many from the local tribes. The main event was Chief Thunderbird against Tiny Mills. “They had been doing construction, and there were chunks of concrete laying all over the floor under the bleachers. As Mills was hammering the hell out of Thunderbird, it began to rain concrete blocks. I was refereeing the match, Holy Mother! Nobody had more guts in the wrestling world than Al Mills. … Mills, he wore that black robe and had that Satanic-look on his face. He walked right through the middle of that Indian crowd. He had a cement brick in his hand. Nothing happened.”

After 11 years, Oeming decided to get out of the wild wrestling business into something wild, but in a completely different way.

He obtained his Master’s Degrees in Science specializing in Zoology in 1955, and Oeming used some of the funds he made from selling his shares in Stampede Wrestling back to Stu Hart to buy a piece of land. Mike Bulat took over the promoting of Edmonton.

“In ’59, I had decided, I had graduated from U of A, and I had a Bachelor’s and Master’s, and I had bought a nice chunk of land about 15 miles east of the city of Edmonton. I was deadly determined I was going to set up my own game farm, and I couldn’t promote the wrestling and do that too,” said Oeming. “So I decided that would be it. All the old guard, the oldtimers, they liked what I had been doing over the years, came to me and said, ‘Don’t do it. Don’t do it. … What a business it is.’ Well, I decided I had to do the other thing, and you have to close one door behind you.”

The Alberta Game Farm opened its gates on August 1, 1959. The obituary for Oeming described the farm as such: “Over the next twenty years, the Alberta Game Farm would become famous as a vast reservoir for vanishing species due to the breeding programs that were implemented. Exotic animals such as white rhinoceros, silver back mountain gorillas, reticulated giraffe, nilghai, Przewalski horse, Peary’s caribou, Siberian tigers, snow leopards, Siberian lynx, Barahsinga deer, greater and lesser kudu, common eland and giant sable were but a few of the 166 species and 3,200 head of mammals and birds that were raised and fully acclimatized to year-round northern Alberta weather conditions.”

Oeming did keep up with the wrestling a little, at least some of his old friends.

“I stayed in touch with Stu. He was bemoaning the fact that you now had a classy bunch of wimps as wrestlers, that couldn’t drive that far, they had to have this, and they had to have that,” said Oeming.

Bob Leonard recalled a visit to see Oeming at the farm:

In 1970 or ’71, during Stampede Week, Dory Funk Jr. and I rode from Calgary up to Edmonton with Stu for a show, in his Cadillac limousine. We had an early media interview, and had the afternoon to kill. Stu arranged for us to go out to Al Oeming’s Alberta Game Farm, about 20 minutes east of Edmonton. The famed locale was closed that day but Al’s young son Eric, about 12 or 13 years old, took us on a driving tour in the limo. That was seeing this amazing creation of Al’s in style! And as it turned out, the tour gave us a couple of heart-stopping moments.

We got out at a large, seemingly empty enclosure with a very stout, high wire fence, and Eric headed through a rather complicated double-gate system. Once inside, he called out loudly and within a few seconds we saw several full-grown Siberian tigers loping toward him. Eric didn’t retreat as they surrounded him; rather, he jumped up on the shoulders of the biggest one, tousled his ears and laid along his back! Stu, Dory and I just gaped at this fearless young guy as he played with the big cats for a few minutes, then nonchalantly came back out and away we went.

We eventually pulled up beside a very long and narrow enclosure, with a single sleek, spotted cheetah — the fastest-moving animal in the world — prowling inside. Eric told us this was Tawana, Al’s frequent companion when he visited schools, conferences and other gatherings across Canada and abroad to publicize wildlife conservation. Asking if we’d like to meet this handsome fellow, Eric headed into the compound and Tawana streaked toward him. Eric snapped a leash on the cheetah’s collar, and walked him over to Stu’s limo. No cautious cat, Tawana climbed confidently through our open door and into the back seat where Dory and I were sitting, sat down and riveted us with a sharp-eyed once-over. He sat in the car for perhaps a minute or two while we admired him, then apparently finding us rather uninteresting, padded back out. Dory and I barely drew a breath while Tawana inspected us, but Stu was quite amused by it all

Oeming may have had some fame through wrestling and as “The Boy Promoter” but becoming a spokesman for wildlife made him a well-known name. There was a CBC TV show, Al Oeming: Man of the North, and the National Geographic special Journey to the High Arctic, as well as participating in feature films like Land of the Black Bear, Window on the Wilds, Galapagos, Wild Splendor.

Al Oeming in northern Alberta in 2001. Photo courtesy Oeming family.

He visited countless schools across the country talking about respecting the gifts of nature. In 1964, Al was awarded the Everly Medal for Excellence in Conservation by the United States Government. He toured communist China in 1964 as an official guest of the Chinese government to observe the breeding programs in rare and exotic species throughout China. The tour led to many years of successful trading in exotic species between Chinese zoos and the AGF. In 1972, the University of Alberta awarded Al an Honorary Doctorate of Law degree.

Al Oeming on Lost Lake in 2005. Photo courtesy Oeming family.

The year 1978 brought some changes. Al married Gina Mrklas, and the Alberta Game Farm changed focus to cold climate species only. Polar Park became the successor to the AGF and dholes, sable marten, Pallas’ cats, lesser panda and Chinese red fox were imported from the Harbin Zoo in Harbin, China in exchange for white rhinoceros and llamas. The business of both the Alberta Game Farm and Polar Park was accomplished by Al with no public grants or government assistance.

Until the end of his days, Oeming continued to be active both on his farm and abroad, including a campaign to band great grey owls in Flatbush in northern Alberta.

Oeming died March 17, 2014. He was survived by his older sister Virginia Lorenz, his younger sister Elsbeth Grant, his children Todd Oeming, Eric Oeming, Lorelei von Heymann and Thelon Oeming, as well as grandchildren Dr. Bethany May Oeming, Robert Oeming and ,Minka von Heymann.

RELATED LINKS