In 2006, Newt Tattrie talked a little about his history as a trainer: “Nobody likes to admit that they were trained by somebody else. They always like to think that they were born that way,” he joked. Today, some of the men that were trained by Tattrie in a barn outside Pittsburgh share their memories of the man.

Tattrie trained names that are significant in wrestling history — Larry Zbyszko, Nikolai Volkoff, Bill Eadie (Masked Superstar, Demolition Ax), John Minton (Big John Studd, Chuck O’Connor), Downtown Bruno Lauer, Brian Hildebrand (WCW referee Mark Curtis) — and many others who never made it quite as big, but take pride in what they did as professional wrestlers as well.

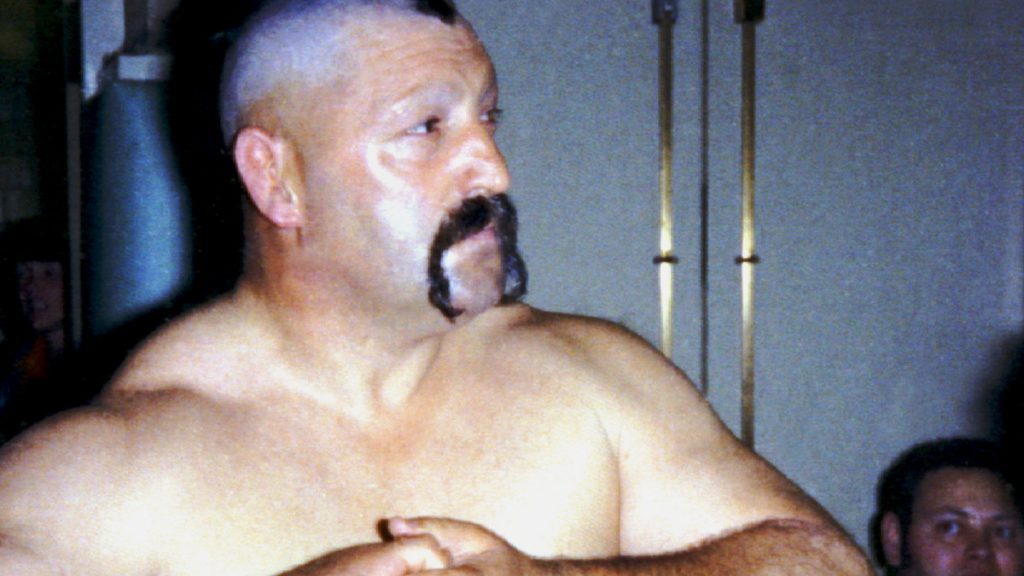

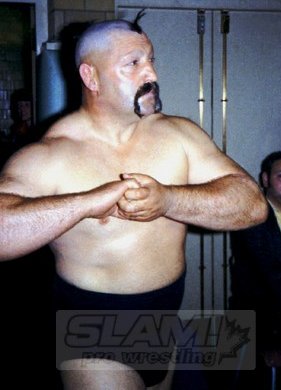

Newt Tattrie as Geeto Mongol. Photo by Steven Johnson

For example, TC Reynolds.

“Geeto was old-school all the way. When you trained with Geeto, he did things like rub your face in the mat, thumb you in the eye. I guess, in a way, he taught you not only about pro wrestling, he taught some self-defense too,” recalled Reynolds (Tom Buzanoski), who would finish his training with Dominic Denucci when Tattrie moved to Virginia Beach, Virginia. “He’d wrestle with you; he’d put his hand behind your head and throw you down to the mat until you learned balance. He was a tough, old bird.”

Like Reynolds, Tony Gennaccaro took away lessons beyond wrestling, skills that still come in handy today as a Pennsylvania State police officer.

“Geeto was a tough guy, a real shooter. He taught me a lot, and I still use it today as a cop,” said Gennaccaro, who wrestled as Pac-Man, Tony Frank, and Jason Friday. “If you do what Geeto taught you, very few people can kick your butt, that’s for sure. He was a feisty guy.”

Part of that toughness, feistiness came from Tattrie’s upbringing. He was born in Springhill, Nova Scotia, but grew up on the streets of Toronto, leaving home at age 12. (He had a sister in Toronto.) He found a gym where he thought he could learn boxing, but instead found Gene Dubois (“Bearman” Dave McKigney) training wrestlers. He had a rough start, not finding enough work, so he turned for a time to the oil fields of Alberta.

It was in Alberta, in a library, where he came up with the idea of the Mongols gimmick, which led to full-time work in wrestling for the first time.

His partner was a monstrous Josip Peruzovic, a Croat who left the Yugoslavian weightlifting team in 1967, while at a weightlifting tournament in Vienna, Austria, and defected to Canada.

Tattrie took Peruzovic under his wing as his tag team partner, Bepo Mongol.

“Practice in the ring, Stu Hart’s house, too,” recalled Volkoff on Friday, who said the “Geeto” name suited him perfectly.

“He was a funny guy. He was much older than me,” said Volkoff. “He’s Geeto. His wife is Ukrainian, and Geeto means grandfather. So they gave him the name Geeto.”

Geeto and Bepo Mongol. Courtesy Chris Swisher

In 2006, Tattrie recognized his influence on Volkoff. “Bepo was always real appreciative, though, because I took him when he couldn’t even speak English. And I’m glad he’s done well,” said Tattrie, praising him as “a square shooter, an honest, honest, honest guy. He hates liars.”

The Mongols tag team was a hit, and, when Peruzovic left to become Nikolai Volkoff on his own, Tattrie turned a local high school history teacher, Bill Eadie, who had already trained some in Tattrie’s barn / gym, in Butler, Penn., just outside Pittsburgh.

“Bill Eadie was a fast learner,” said Tattrie, who had about six weeks to get Eadie ready to go to Japan with him.

Killer Kowalski is usually associated with training John Minton, who became a star as Big John Studd, but Minton was originally from Butler and learned at least some of the ropes in Tattrie’s barn.

Like with Studd, the training of Larry Zbyszko is usually associated with someone else — Bruno Sammartino — rather than the man who did the bulk of the work, Newt Tattrie.

In an interview with GeorgiaWrestlingHistory.com’s Mike Sempervive in March 2004, Zbyszko described Geeto’s barn: “He had a big — kinda like a farm, with a barn on it, outside of Pittsburgh. And me and Bill Eadie, and another guy, Ron [the late Ron Matteucci], used to work out in Geeto’s barn. And once in a while Geeto would be there too, and we’d mess around, and ride some horses. You know, Geeto was a hell of a guy, and was instrumental in giving me a place to work out, and helping me out a bit. He was running some shows that I used to start on back there.”

Larry Zbyszko in 1974. Photo by Steven Johnson

In the 2006 conversation, Tattrie recalled Zbyszko (Larry Winter) around his barn. “Larry knew Bruno, but I had a gym and they told him to come up to the gym where I was at. So he worked out at the gym up there,” said Tattrie. “He was just out of high school.”

The most unlikely success story to come out of the barn was Bruno Lauer, who started hanging around when he was just a teen.

He was a little guy, and he asked me at the gym in Pittsburgh, he says, ‘Can I come in and just help you, get guys ready and everything?’ I said okay,” recalled Tattrie. “So he came in, and while the boys were training, he used to walk around the ring and act as a manager.” Tattrie would use Lauer on shows as manager Dr. Lennerd Spazzinsky.

But Lauer had drive, and after an apprenticeship in Memphis as Downtown Bruno, became manager Harvey Wippleman in the WWF.

RC Reynolds admitted he didn’t see that one coming: “Out of all the guys down there that we thought would go nowhere, because he was just a little squirt; he ended up going up with Vince.”

Like Lauer, Ken Cerminara got into wrestling when he was young — his uncle was a floor manager at Channel 11 where the wrestling was taped; though he was too young to sit in the audience, his uncle let him watch from behind the glass. Once he was big enough, Cerminara started going to Geeto’s to train, and would eventually wrestle as The Sicilian Beast (and other variations of The Beast).

“He took me under his wing, he helped me out,” said Cerminara, describing the barn. “There was no heat, no air conditioning, so in the summer, it was 100 degrees-plus; in the winter, it was bone-breaking cold. He used to just stretch the heck out of me. He was a heck of a guy strength-wise. He would just torture us, but no bad language. If you said a bad word, he’d come after you — it was hilarious. It was like Catholic school in a wrestling ring. Good memories.”

There a good memories about a half-mile down Route 8, too, where Ann and Newt Tattrie ran “Geeto’s” — a roadside ice cream stand. “That was always a highlight after the workouts, to go get ice cream,” said Cerminara. They also sold fruit and vegetables for a time.

Of all his students, Randy Briggs — wrestler B.A. Briggs — kept in touch the most, simply because he had connections in Virginia Beach, where Ann and Newt settled, and became heavily involved in The 700 Club there. He’d call every so often, and when he was in the area, would take Geeto out for lunch. The last time, Geeto wanted to go to the beach “to check out the stock,” laughed Briggs, who trained with Tattrie for about a year.

Much of what Briggs took away from Tattrie was beyond the wrestling.

“He wasn’t very educated, but he educated himself,” began Briggs, who considered Geeto like a grandfather, one who once gave him a gave to get around.

Tattrie carried around a copy of the 1963 book, My Utmost for His Highest, by Oswald Chambers, and would continually refer to it and make notes. Briggs said that Geeto was involved in spreading the Word of God, and would say, “Randy, always look up, unless you’re walking through a cow pasture.”

“He always had something funny to say, without even trying,” chuckled Briggs.

TC Reynolds.

Reynolds acknowledged that Tattrie was even pretty religious in Pittsburgh. “He’d always try to get the boys to go to church with him, some did and some didn’t. You’d go to church with him, and he would sing so loud and he was a terrible singer,” he cracked.

Besides the training, Tattrie’s other big impact on the Pennsylvania wrestling scene was his constant battle against the athletic commission, which required their own referees and timekeepers at the shows — funds that had to come out of the promoter’s pockets. And Tattrie didn’t always want to reach deep into his pockets.

“He was real instrumental in getting rid of the commission, he took them to court, the athletic commission,” said Ken Jugan, a Pittsburgh native who still wrestles and promotes as Lord Zoltan. “He was a typical old-school promoter. He tried to get the guys as cheap as he could and promote shows.” Many of the names on Tattrie’s shows would be knockoffs, like Baron Mikel Donatelli instead of Baron Mikel Scicluna.

Tattrie wasn’t shy about his dislike of the bureaucracy, said Reynolds: “Geeto brought a wheelbarrow full of pennies, nickels and dimes in to pay the Athletic Commission.”

As a promoter, Tattrie primarily used his students on the shows, and was reluctant to get big names.

Tony Gennaccaro and Ken Jugan in 2010. Photo by Mike Mastrandrea

Cerminara does an impression of Tattrie: “You’ve got the high-priced stuff, and the low-priced stuff. I will always take the low-priced stuff,” he mimicked. “He would take a guy, and if he kind of resembled, a big black guy would be Hobo Brazil instead of Bobo Brazil.” And Cerminara was named the Beast because he looked like the better-known John Yachetti.

“I never had a bad payday from Geeto. He was fair,” said Gennaccaro. “But if the show was a flop, he wasn’t going to lose money on it, that’s for sure.”

“When it came to the business, he protected the business,” explained Briggs. “But he was really smart about the business, and he was very shrewd about how he did things.”

There is a loyalty that these men still have to Tattrie, who taught them far more than grappling skills.

“You never questioned anything he said. You just went out there and did it,” said Gennaccaro, who as Pac-Man with his yellow mask, wrestled Tattrie often. “A lot of people can say that they learned a lot from that man.”

Cerminara learned how to say goodbye too.

“The one thing that rubbed off on me, all these years later, when he would talk to you on the phone, when you were about to hang up, he would say, ‘Okay, bye, bye, bye, bye.’ And I started doing that, and over the years, people think that’s my thing, but it’s me influenced by him. To this day, I still say that to people on the phone.”

With Newt Tattrie — Geeto to his wrestling friends — in the ground, buried on Tuesday, that is all that his charges are left to say: “bye, bye, bye, bye.”

RELATED LINKS

- July 12, 1999: Newt Tattrie’s gimmicks, from Mongol success to smelly Skunkman

- July 26, 2013: Geeto Mongol dead at 82

- Nov. 10, 2003: Present celebrates past at wrestling legends event