After the Cinderella victory of the Montreal Alouettes in the 1970 Grey Cup, defensive tackle Mike Webster expected to return to the Canadian Football League for a seventh season. Management had a different idea. Former NWA World Heavyweight champion Gene Kiniski, who met Webster at the gym, saw the potential for Webster to make a seamless career change.

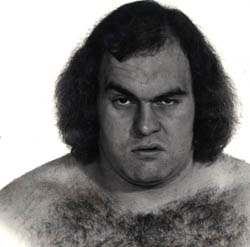

“Iron” Mike Webster

“That was a time when we were trying to establish a players’ association in the CFL, and I was the rep, the agent, for the Montreal Alouettes,” Webster told SLAM! Wrestling. “I had a reputation as being a locker room lawyer. I orchestrated a strike in Montreal, we didn’t show up for camp on time because we weren’t being treated properly, and on and on and on. All the agents from the various clubs got together in Winnipeg — I forget what year it was [1971], and the whole league didn’t show up for camp on time. So they were not happy with me, and that’s the reason that Gene figured they didn’t want me there, because I was a shit disturber.”

“I immediately went into wrestling. Gene turned to me and said, ‘Well, if they’re not going to use you, do you want to come with us?'” Webster said, guessing he only trained for a couple of weeks, mainly learning how to take bumps. “Gene took me down to old Western Gym in the downtown east side of Vancouver (Main and Hastings) and schooled me — Sandor Kovacs wanted a big man who could take big bumps in the territory.”

The boss saw something in Webster. “What he liked was I was large. I weighed over 300 pounds at the time. I could really take bumps.”

In the kayfabe era, a premium was placed on maintaining the legitimacy of the sport, and a Notre Dame and CFL lineman was as legit an athletic pedigree as there was. The established stars in the Pacific Northwest territory did their part to get Webster ready for the ring.

“I took high backdrops, and wasn’t afraid to have the likes of Don Leo Jonathan or John Quinn, who are all 6’6″, 6’7″, airplane spin me, throw me out of the ring, and all that stuff. When I wasn’t in the ring, I was at the door to the dressing room watching guys in the ring, and this is where Duncan McTavish (Matt Gilmore) and I would talk. Duncan would say, ‘Now watch this. Now you never do that type of thing. That’s ridiculous.’ That’s where Duncan and I really made a connection.”

The impact of the recently-deceased Scottsman on the fledgling grappler was immense, relates Webster.

“When I was breaking into the business, of course it was Gene that really broke me in, but Duncan was sort of like Gene’s deputy. He was so giving of his time and his knowledge, which impressed me. So many guys in the business, they’re very territorial, they’re very guarded, very secretive. Duncan was always open and generous and always willing to help,” said Webster. “He’d been around the world working, and he had so much knowledge — and he was generous. He would not hesitate to share little bits and pieces, little tricks of the trade. I was, at the time, trying to learn how to run a match and be a good dastardly villain. He was always there for me. If I went to ask him a question, he was always willing to answer. He came to me many times and made suggestions in a way that they weren’t hard to take. They were so palatable. He was such a friendly and supportive guy. It wasn’t taken as criticism. I just have great, fond memories of Duncan. He was so appreciated by the fans.”

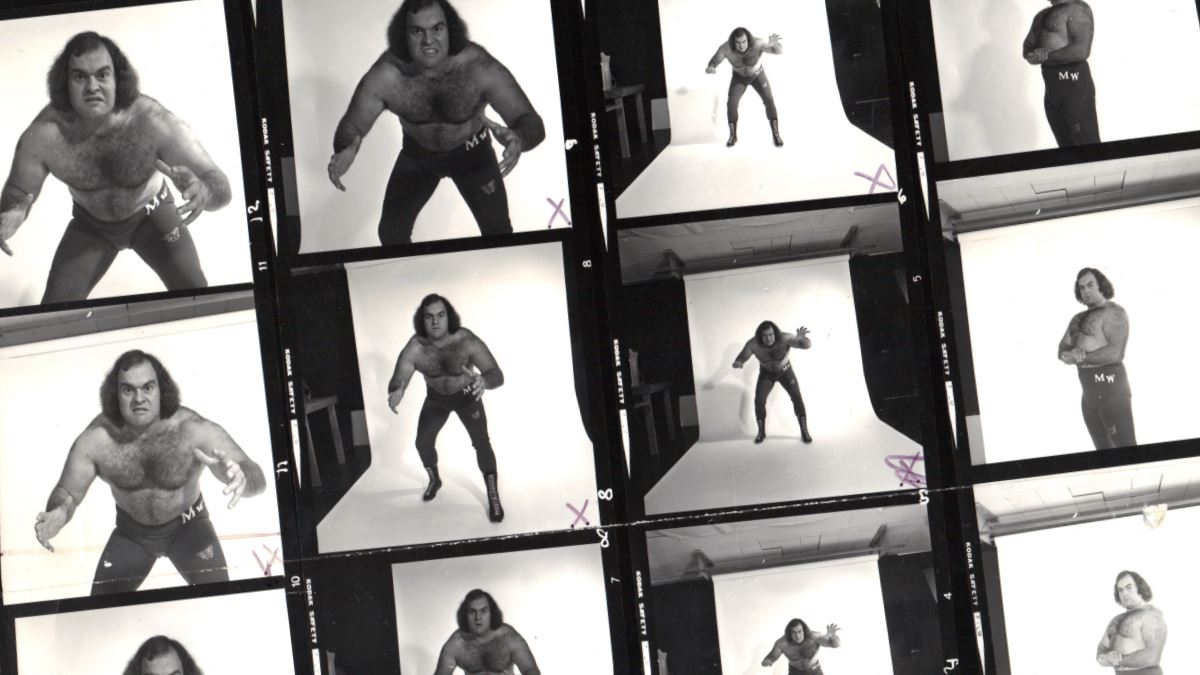

Mike Webster stomps around ringside.

“I was originally Big Mike Webster — and stayed that way in some territories. On one road trip into Washington State I was billed as Iron Mike, I think Port Angeles was the first time, and some promoters picked it up — it followed me to Florida. Gene and Sandor [Kovacs] had a business relationship with Eddie Graham — I was to debut in Vancouver [Spring 1971] — learn the ropes for a few months, then head for Florida.”

Down south, the future psychologist was able to learn from some of the true masters of how to get a crowd blazing hot.

“We went to Florida in winter 1971 and stayed for nearly two years — I thought I was well prepared. Every territory has its own style. I was a student of the business. After my match I would stand outside the dressing room and watch the other wrestlers. Frankie Cain (Great Mephisto), one of my mentors, he was an old ‘carney’ wrestler — maybe weighed 185 pounds, had a face like a road map. Many times he had me squealing — taught me to ‘shoot’ some. He couldn’t read, so he drove and I read him stories. My wife, Moira, trimmed and dyed his beard. I love the guy! He once told me, ‘There are no new moves, take what you like, what fits your style, and make it yours.'”

Touring the state with Cain and The Zodiac (Bob Orton Sr.) in tag battles against various combinations of Johnny Walker (the future Mr. Wrestling II), Louie Tillet and Jack Brisco, the road trips provided the opportunity for Webster to appreciate the larger than life characters behind ring personae — and the Florida locker room was hardly lacking in the strange but true department.

“Bob Orton Sr., one of the great characters of the business. As he had a very bad back, he took his time in the ring, he taught me to SLOW DOWN! He was a laugh a minute. He was at his best when he began to spout his conspiracy theories. It would frustrate him to no end when others didn’t buy in. Boris (The Great) Malenko was my landlord in Tampa. My longest memory of him is that he kept my damage deposit after we left. He accused us of running off with his damn roasting pan, which we did not do! He was a master of the pile-driver — I have a picture of him driving me headfirst into the mat.”

Across the ring, Webster was learning not only from brawlers like Malenko but from the best fan favorites around.

“Tim Woods (as Mr. Wrestling) was the consummate babyface. I used to study him, looking for the things that the fans loved most about him — as those would be the things I went after. Johnny Walker I would describe as a journeyman. I always thought that if he was taller and had more hair he would have been one of the all-time greats. He taught me much about how to run a match — a good ring psychologist.”

The Pro (Doug Gilbert) and Mike Webster.

The first championship of Webster’s career came about on May 31, 1972 when The Pro (Doug Gilbert under a hood) beat Malenko and Bob Roop in Jacksonville. With Gilbert soon assuming the “Redbeard” identity, the team was part of the stable of Bobby Shane along with Shane’s wife Sherri (a Surrey girl who Shane met during his own 1968 run in British Columbia), and Shane’s male valet Steve the Body.

“I always enjoyed working with Bobby as he was a master showman. It was easy to play a myriad of angles around him being my boss, me being protective of Sherri — he abused her in the ring, him getting upset with me as I was interfering in his domestic affairs, Bobby playing Doug and I off against each other, etc.”

Bobby Shane died in a plane crash in 1975. Another Florida heel that Webster knew, who also died mid-career, was the controversial Big Bad John. “He pretty much kept to himself at that time and in that place. He was an interesting guy — someone you’d like to know — but he was kind of a ‘porcupine.’ You’d like to get closer to him but the prickles kept getting in the way.”

When Webster returned to Canada in late 1972, he achieved nationwide notoriety by being teamed with Bugsy McGraw (Mike Davis), whose maniacal bald-headed character The Brute was an imposing force in weekly TV interviews with Ron Morrier. Kovacs once said he was his all-time best ticket-selling heel.

“The Brute was a different kind of guy. Hard to get to know. Not big on the social graces. He drew a lot of heat because he acted like a lunatic. Not my style. I disagreed (silently) with his approach as it reinforced the stereotypical heel. Ron was a nice man — always impressed me with how he managed the egos he had to interview.”

The Brute and Mike Webster.

Webster’s interviews were not the heel norm, as they were full of philosophical references similar to the flower-power movement on college campuses and he would always call Morrier “Daddy-o.”

“I was one of the first likeable heels. I was uncomfortable with the cookie cutter heel and decided that I could get even more heat with a morally relativistic approach. With the fans in mind, my credo was, ‘Easy to follow, easy to swallow.’ Everyone loved to work with me. I was to wrestling what B.B. King is to the blues guitar. I was a minimalist. I always thought of the fans first, then the business, and lastly me.”

In a rare title change in the Vancouver suburb of New Westminster on New Year’s Day of 1973, the popular four-time champion duo of Dutch Savage and Steven Little Bear were subdued, and the powerful new heel team of Iron Mike Webster and The Brute went on a rampage for the next half a year, the second longest reign in the history of the Canadian Open Tag Team titles.

The still-green Webster had a lot of guidance as his education continued against top-shelf talent like Steven Little Bear — “a great babyface, always ready to coach, taught me difference between doing it the ‘easy way’ and the ‘hard way with a sturdy dropkick!'” — and the “jovial, always smiling, easy to work and travel with” Dean Higuchi / Dean Ho.

TV victories to establish the dominance of the team were scored over the likes of scientific local carpenters like Eric Froelich (“a hard worker, had a faithful following and tons of experience, very aerobatic”), and Jack Bence, who Webster recalled as “quite a character, had tons of stories, and was living proof you can ‘work’ as a senior citizen.” Two Winnipeg veterans also made an impression on Iron Mike, the gap-toothed villain Bulldog Bob Brown and referee Roy McClarty.

“Bulldog Bob Brown and I often travelled together, great guy, salt of the earth, had a litany of corny jokes and silly ribs but would be deeply offended if you didn’t ‘put him over’ every time he told one or pulled one,” laughed Webster. “Roy, not a good guy but a great guy — everyone’s father. He was always available to answer questions and give hints. I kept contact with him after he retired from refereeing when he became the janitor at his kid’s high school.”

While co-holder of the tag title, The Brute dethroned the nine-month reign of Pacific Coast heavyweight champion Gene Kiniski in a rare heel vs. heel feud to take the area’s major singles title, but only held it for three weeks before losing it to the popular Sean Regan (real name Gerry Murphy). This set up Webster to avenge his partners’ loss, and the former footballer upset the Irishman in Vernon, BC, on June 15th for his first singles title.

Fans of the syndicated All Star Wrestling TV show, used to the formulaic three uneven match-ups, were glad to tune in that summer of 1973 when the only bout scheduled for the hour one week was Regan challenging Webster for the championship in a best-of-three falls affair.

John Quinn slams Mike Webster.

The studio audience was deafening when the bout was tied at one each and the time limit near. Regan desperately tried to lift Webster in his Donegal Drop (named for Regan’s hometown), a brainbuster suplex move. Webster just as desperately hooked his arm around the top rope to block it, in one of those old-school moments when “real” and “fake” intersected.

“I got along fine with Regan, a good guy, full of blarney, another European style wrestler, sold everything, consequently the big finishes ended up meaning little,” recalled Webster. “Those English shooters, we had a saying, they were ‘more interested in the scrapbook than the bankbook.’ We were about to go on a big tour around the province, and I knew it would mean more at the box office if I held the belt and the babyface was chasing me. He worked a little on the stiff side and it took me awhile to get him to ease up. I remember that match and I had no intention of going up for his finish because of what could have happened on the way down. We did it my way and the fans were primed to buy tickets at the arenas to see me lose after I escaped with the 45-minute draw on TV.”

Ultimately for Webster, there was a bigger prize on his mind. “I had been accepted to do post-grad work and would be cutting back to return to school,” and so the tag titles were dropped to Big John Quinn and Gerry Romano (Jerry Monti) in Vancouver on July 16th.

Two weeks later, a loss in a six-man tag with The Brute and Kiniski against the new champs and Savage resulted in The Brute attacking Webster and ending their partnership, and his Pulverizer bodyslam enabled him to recapture the Pacific Coast belt from Webster only one week later.

Just like that, the hated double champion was waving goodbye to his new-found fans.

“I didn’t feel bad about losing belts so quickly. I had made the tough decision and thought in the long run it was best for me — and giving up the belts was part of the decision. I was basically done as a full-time worker in the territory. I didn’t mind working as a babyface as I already was experimenting with a shift from the old days of good vs. evil toward moral relativism and letting the circumstances dictate where I fell on the good-evil continuum.”

Webster with shorter hair in 1974.

Webster completed his Master’s Degree from Western Washington University in 1976 and Doctorate in 1981, with his last title victory coming with The Black Hand (Joe Turner) winning the Georgia Tag Team titles over Ted and Jerry Oates on April 24, 1976.

“I worked occasionally during both, more so during Masters. I did mystery wrestler shots and and filled in for sick and injured masked men while studying full-time,” said Webster, listing territories such as B.C., Washington, Oregon, Puerto Rico and Hawaii. “I made more money wrestling than I did during my years in football — however, not as much as I could have (should have?). I never worked on a contract, it was always for a percentage of the gate. Some promoters were better than others — none of us could figure out the percentage. I always felt like I got a fair shake around home from Sandor Kovacs, Gene Kiniski, Don Owen, and even as far west as Hawaii and Lord Blears.”

Webster has fond memories of his time in the ring, and shared a number of observations about similarities between football and wrestling.

“The biggest thing for me was the camaraderie. I loved that about football, being a part of a team. You’re getting paid to be with the guys, you go out and you play a game that you love, you play hard and you lose hard too. You do it all as a group, and everybody’s supportive of each other, mostly everybody’s supportive of each other — there’s always some elements on a team where they’re pulling in another direction. Mostly it’s like a big family. Boys will be boys, goofy at times, immature and haven’t grown up, but it was a wonderful, wonderful experience.

“And then going to wrestling, that was the thing that I liked best about wrestling. I liked the idea that it was, to me, wrestling was an art. To be able to, through the thing that I did in the ring, be able to affect people who were not connected to me in any way, emotionally or relationship-wise, or anything — I’m speaking of fans. To be able to just by choreographing something in the ring to be able to get people to have an emotional experience, an emotional reaction to that, I liked that. I liked the skill part of it, I liked learning the skills part of it — that was a good part of wrestling. And that’s also comparable to football, even in my position as a defensive lineman, there are certain skills that need to be mastered, not as fine skilled as say a quarterback or a pass receiver or somebody like that, but it’s still a skill.

“Mastering and applying them, and applying them successfully, and I’m thinking of both professions now, the football and the wrestling, mastering and applying them successfully, and then getting patted on the back for doing so, is a great builder of self-esteem. I liked that angle. I liked the skill part and then applying it. But then there’s always the camaraderie part of it. I really enjoyed being with the guys, being goofy. We were all young, right, in those days. It was like being part to be a part of the French Foreign Legion or something.”

And in recapping his career, Webster quoted from one of his own TV interviews: “So Mr. Morrier, one might say, with the greatest of humility, that Iron Mike is somewhat of a trendsetter.”

— with files from Greg Oliver

RELATED LINKS

The evolution of Mike Webster: Psychologist … and head of the RCMP?