Ben and Mike Sharpe take their place in the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame this weekend. It’s a fitting tribute for two giant men who stomped out a great legacy — from their youth in Hamilton, Ontario, to serving their country in the Second World War, to the rings of San Francisco, where they headlined for a decade, to Japan, where they made Rikidozan a star.

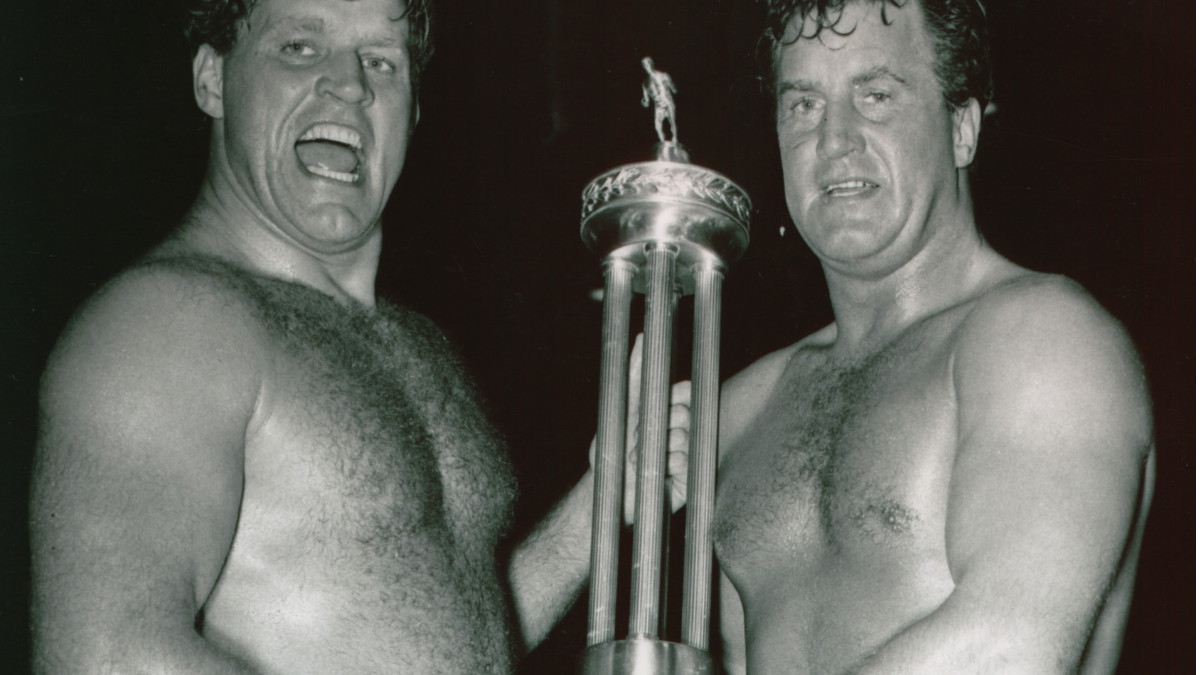

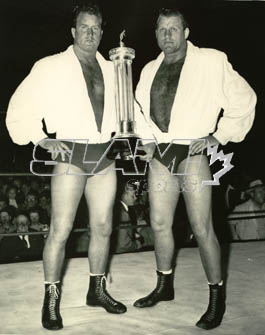

Ben and Mike Sharpe in the ring in 1951. Courtesy The Sharpe Family.

The Sharpes will be posthumously inducted in the Tag Team category, and their family will be out in Amsterdam, NY, for the ceremony.

The call came in to Karen Sharpe-Grubert, daughter of Ben, in December 2009 about the honour. “You know, we lost dad in November, so the holidays are always kind of hard, so it’s funny that you should call around now,” she said. “We’ve been talking a lot about him, going places that we used to take him. It means a lot, it’s really, really cool that he’s being honoured like that, along with Uncle Mike.”

The story of the Sharpes and professional wrestling is a typical one for their time period. Despite their good looks, excellent physiques and charisma, with Whipper Billy Watson ruling the roost in Southern Ontario, they would be forced to hit the road to find stardom.

Ben Sharpe, born March 18, 1916, was six years older than his brother, Mike, who came into the world on July 11, 1922. The family was led by Det.-Sgt. Digby Sharpe of the Hamilton City Police force, who was an imposing 6-foot-4, 240 pounds; he was well-known around town, with his immaculate uniform and his shiny shoes. There were four Sharpe sisters as well, Yvonne, Dolores, May and Marguerite.

Attending Westdale Secondary School in Hamilton’s west end, both Ben and Mike grew into impressive physical specimens, much like their father. Ben was 6-foot-5, but around 230 pounds, and Mike an inch taller, and a hefty 265 pounds.

In 1936, a 20-year-old Ben Sharpe went to London, England as an oarsman for the Canadian Olympic rowing team. He carried the flag in the parade of athletes and shook hands with Adolf Hitler. Sharpe could tell that a war was brewing and wrote home to warn his family.

“He wrote home a lot of letters to his father,” said Sharpe-Grubert. “He had told his father ‘Daddy, there’s going to be a war. There’s German soldiers billeted everywhere, they’re in the streets and everything'”

While the Olympics were a wonderful experience, Ben was bitter about the finish. “We were really fast,” he recalled in a 1979 interview in the Hamilton Spectator. “At our trials at Port Dalhousie, we set a record speed which has still never been broken, but they promised us a special boat for the Olympics. The boat we received had originally been built for the British team, but they discovered a warp in the bow which slowed it down an awful lot, and then they gave it to us.”

It was an oft-repeated saga, said Sharpe-Grubert. “Now, whether that was true or not, I don’t know, because my dad was really big on telling tales.”

Ben Sharpe had some early experiences in professional wrestling around Hamilton, and designed elevators for the Otis Elevator company. But then the Second World War changed everything. When war was declared, Ben enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force and was stationed in England as a physical fitness instructor. At 6-foot-5, he was too big to get into the cockpits of the planes he dreamed of flying. Like his father, the policeman, a natty uniform was important to Ben, said his daughter. “He was really vain, and he didn’t like how the uniform fit, so had all of his uniforms tailor-made.”

Wrestlers Pat Flanagan and Mike Sharpe whoop it up with a gang of young admirers in March 1947. — Toronto Telegram

Mike Sharpe, an excellent athlete as a teenager, entered the RCAF when he was old enough, beginning as an armourer, often being called upon to load bombs onto planes given his size.

Digby Sharpe, son of Mike Sharpe, and, like his grandfather, also a policeman, shared a story his father told him about landing in Britain. “When he got off the plane, I guess the Queen came to welcome or inspect the Canadian troops, as she was looking down at the troops, she got to my father, looked at him, looked up at him, looked down at him. She says, ‘My, you’re a big one!’ and then went on with the rest of the inspection.”

The brothers had been apart almost four years by the time Mike arrived in England, and Ben saw dollar signs. Already enamoured with the grappling scene, wrestling in small towns, he recruited his brother into the grunt-and-groan racket.

“That’s how they made money during the war. He said it was the grandest time he ever had was during the Second World War,” said Sharpe-Grubert.

Not yet the noble Lord James Blears, the common man Jan Blears met the brothers in England, when he was wrestling while on leave from the Merchant Navy. “I wrestled Mike Sharpe in Middlesborough. Great, big raw-boned guy. Jesus! Big, tough son-of-a-gun,” recalled Blears, who would later face the Sharpes in the ring countless times in California.

With the war’s end, the Sharpes turned down a British promoter’s request that they stay and wrestle, and headed home.

Though they never became major stars on the Ontario circuit — Whipper made sure of that, as he wanted to protect his turf and his drawing power as the area’s top babyface — the brothers did have a major influence, and were a drawing card, especially locally.

Don Leo Jonathan met the Sharpes when he was still in the U.S. Navy, and they were working out in San Francisco. Mike Sharpe had a huge influence on the Mormon Giant. “He was one of my idols, a guy that I tried to be like, try to wrestle like. For most of the young guys, there’s somebody that sort of fits their style, that they figure, ‘Well, maybe I’ll try to be like that’ or ‘I like what he’s doing’ or ‘I like the looks of the guy, and have a body like that.’ Mike had a beautiful body, and he worked hard at it. He was impressive when I was 18 years old.””They were heroes of mine,” said George Scott, who would end up in the wrestling business first as one of the greatest tag team wrestlers ever, and then as a booker. “I used to go sit on their door step.” They would work out at the YMCA, and help others with both grappling and weightlifting.

After four years of grinding it out in Ontario, the Sharpes picked up to move to San Francisco. “We lived on peanut butter in cheap hotels,” recalled Ben in 1979. “When we finally flew into San Francisco, we had about 75 cents between us.”

Working for promoters Joe and Frank Malcewicz in San Francisco, the Sharpes were the stars of the promotion. They would hold the tag team titles in the territory 18 times. San Francisco wrestling announcer Walt Harris recounted his first meeting with them. “I was walking by the Civic Auditorium in downtown San Francisco one time, and these two guys were walking ahead of me with suitcases. I guess they’d just come to town. By God, they were the biggest men I’d ever seen in my life at that time! Mike and Ben Sharpe, they were huge.”

“Had I been in a position of power in any territory, they would have been my main eventers because of their looks, their wrestling ability. They were just fantastic,” said the late Bob Orton Sr. in 2002.

Known for their tough, knock-‘em-down style, the Sharpes made “the so-called Pier 6 brawls look like a quirt meeting of the Monday Night Sewing Club,” the Humbolt (Calif.) Standard concluded after they incited a riot in the city’s auditorium.

The Sharpes did actually venture abroad (but not a lot!), especially St. Louis, and back home to Hamilton, winning a variety of other championships — but not always losing those belts. For example, the National tag titles were recognized out of Chicago on the Dumont network, under promoter Fred Kohler. The Sharpes won the titles from Billy Darnell and Bill Melby on October 17, 1953 in Chicago, but according to historian Don Luce, no record exists of them ever dropping the titles. (Stan Neilson and Reggie Lisowski were the next to be promoted as champions.)”Joe Malcewicz had them pretty well tied up. He wouldn’t let them go anywhere,” said the late Gene Kiniski. “They had just a different array of wrestlers coming in, and kept feeding them different talent. That’s why the longevity hung in there.”

San Francisco offered easy access to Japan, and the nascent wrestling scene there was about to get a Canadian shot in the arm.

“Few Japanese had television at this time, but a February 1954 tag team tournament featuring Rikidozan and partner Masahiko Kimura was carried on two networks. Thousands of people packed themselves in front of Tokyo store windows to watch the pair take on Americans Ben and Mike Sharpe,” wrote Keith Elliot Greenberg in Pro Wrestling: From Carnivals to Cable TV, getting their nationality wrong. “Soon, Panasonic became the first Japanese company to manufacture televisions. As this luxury became more affordable, Rikidozan established himself as one of Japan’s first true television stars.”

Japanese fans hang on to Mike Sharpe Sr. as brother Ben enjoys a pipe while in Japan. Courtesy The Sharpe Family.

The brothers made many trips to Japan, and learned to appreciate the food and the culture. The love was reciprocated, said Sharpe-Grubert. “They were dearly loved in Japan,” she said, adding that Japanese TV stations regularly came around to interview him in his later years. One of Ben’s sons, Riki, was named after Rikidozan.

Most who knew them would agree there was a difference between Ben and Mike, and not just the six years’ difference in age. They parted ways in 1962, with Ben retiring from pro wrestling and Mike hitting the road, wrestling in many locations he never got to as a tag team wrestler. In fact, Ben was owner and host of the Copperwood Lodge, a well-known restaurant and bar in Colma, Calif., for many years both during and after wrestling.” Mike, he was all about, everything was for the workout and for the business. He was really, really dedicated. Ben, he was a little older, and he was more looking into other businesses besides wrestling,” said Jonathan. “That’s when he opened the bar there in San Francisco, the tavern.”

The years in the ring had taken a toll on Ben, however, and he was in a wheelchair for the last 14 years of his life — but still worked out as best he could. “He had injured his knees, and he had had knee surgery on both knees twice. He had neck surgery done. They had to fuse the vertebrae in his neck,” explained Sharpe-Grubert. Ben contracted an infection in his leg and developed a bad bed sore; a fever followed, and Ben went to sleep on November 21, 2001, at his son Michael’s home in Kingsburg, Calif., and never woke up. He was 85 years old.

“Pop was really well known down here because he used to wrestle in Fresno all the time,” said Sharpe-Gruber, one of Ben’s six children. “It’s funny because somehow the name will come up. My married name is Gruber, and my maiden name is Sharpe. Somebody will mention, ‘Hey the Sharpe brothers.’ ‘Hey, one of them was my dad!’ ‘No way! I used to go watch them wrestle on the weekends!'”

Mike Sharpe Sr. wrestled his final match in 1964, but years later, his son from his first marriage, Iron Mike Sharpe Jr. would become known to the masses through the expanding WWF.Digby Sharpe is still in awe of his father Mike’s athletic skills. “Unbelievable, the quickness. When I was playing college football and wrestling in college, my buddies would come over and he’d just amaze the guys that I knew. And sometimes when it’s your father, you really don’t pay too much attention. It’s like ‘Oh, that’s my dad.’ Well, everybody wanted to come over and visit with my father and talk to my father, and visit. And I was like, ‘What do you guys want to come over to my house for? Let’s go somewhere else.’ Then finally when you hit about 30, you realize, ‘Hey, you know what, this is pretty special.'”

After wrestling, Mike Sr., worked as a brewer for Anheuser-Busch in Van Nuys, Calif., and taught himself to weld, putting together small wrestling rings for children. He was renowned for his charity, said Ben’s brother-in-law, Jake Isbister, in the 1979 Spectator article. “The man was generous to a fault. Anyone with a hard-luck story could count on him for a meal and a bed.” (Many old wrestling colleagues would stay with Mike over the years as well.)

Like his older brother, he was in pain from the wrestling. He had bad arthritis in his hips, to the point where he could barely open legs, and shuffled along. Scared of doctors after so many years in tip-top shape, Mike declined a hip replacement.

On August 11, 1988, while on the way to his sister-in-law’s funeral in Palo Alto, Mike Sr. pulled over to the side of the road and died of a heart attack, with sons Digby and King in the car. He was 66 years old.

As for “Canada’s Greatest Athlete,” Iron Mike Sharpe, though he may have kept the name alive, he was not close to his father. In interviews, he gives his father and uncle little more than a token reference.

There were custody battles through the years in the California courts, eventually with Mike Jr.’s mother, Kathleen, taking their pre-teen son to Hamilton, where she was free of the court order to share custody.

“It’s kind of a sad story,” said Digby Sharpe. “Put it this way, my grandfather and my uncle could see through her, and knew what she was about, and she was about getting my dad’s money. And that’s just what she did. She took all of my dad’s money.”

– with files from Steven Johnson

2010 PRO WRESTLING HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES

Wild Red Berry

Edouard Carpentier

Stan Hansen

Mil Mascaras

Wahoo McDaniel

Danny McShain

Gorilla Monsoon

Kay Noble

Dusty Rhodes

Ben & Mike Sharpe

RELATED LINKS

- Jan. 18, 2006: Iron Mike Sharpe dead at 67

- Jan. 16, 2016: Column: Iron Mike Sharpe: An appreciation

- Previous SLAM! Wrestling Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame coverage