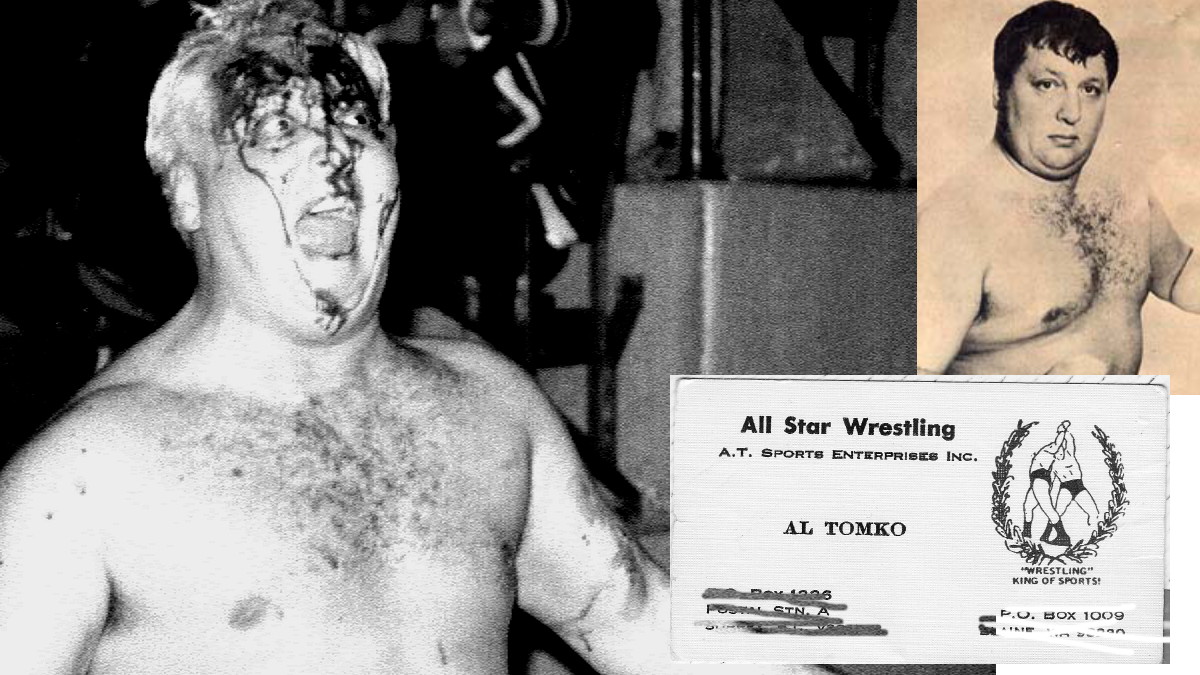

Historian Vern May once said, “To hear Al Tomko tell it, nothing special ever happened in his career, he never had heat with anybody.” With Tomko’s death on Wednesday at age 77, it is time to tell some of his stories.

From his early days in Winnipeg, to promoting in Manitoba and British Columbia, to his post-wrestling life creating pet treats, Tomko marched to his own drum.

Tomko learned he had pancreatic cancer in June, and he had a pacemaker put in. “For the last year, he’s been in and out of hospital many times,” said his widow, Mary. “Even yesterday, he went so peacefully. My sisters were just saying that his pain tolerance must have been so, so high. He did not complain.”

Dealing with Tomko was like dealing with a cantankerous uncle.

Al Tomko as Leroy Hirsch

He was sent a copy of The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Canadians, since he was featured in it. His response to this writer? “I’d say 90% of what you wrote in the book is not true. It’s better to get the facts before you write a book. I don’t mean to be insulting or anything,” he said. “You got all this information, just not from the right people.” Thanks, Al.

What corrections should be made then?

“The best thing you can talk about is myself. I started wrestling in Winnipeg. I had a club called the Olympia Club. I trained 90% of the people who turned pro, from Roddy Piper, plus other people,” he bragged. “Then you mentioned, what the hell is the Italian little guy’s name, [Tony] Condello. He was 5-foot-2, he was a jobber that we used to send down to Minneapolis to job for the other guys. There’s so much that’s not true it’s not even funny. George Gordienko that was a very bad story about him. He’s dead now. He was a very good friend of mine.”

One moment, he would be a little sentimental — “The past is just memories but they creep up on you once in a while” — and the next, he would be addressing his greatness, especially as a promoter in Vancouver, having bought Sandor Kovacs’ share of the All-Star Wrestling promotion, and later buying out Gene Kiniski as well.

“A lot of people say, Al, you’re famous because you’re the guy that had the original idea of Vince McMahon. I started the music, bringing the guys out to music, different lighting, different stuff like that,” he said. “Not as much as he’s got, but it was a start. The Auditorium was packed every match just about.”

The stories are legion from the workers who toiled for Tomko in Vancouver. But Ed “Moondog” Moretti stressed Tomko’s importance even through the difficulties. “He was the boss, he had the right. He gave us work, I’ll give you that. I worked for him for a long-time, off and on. There’s good and bad, but I’d like to concentrate on the good.”

What was the good, Ed? “He wasn’t a hard-assed prick like a lot of the promoters are. The only thing I guess he should have done is concentrated more on business because he had good talent, he really did. There were some guys that really could work. We started to draw money, but when we started to draw money a lot of times, he’d pull the rug out from underneath us. I don’t know why, to this day, I don’t know why.”

Tomko, who was born November 22, 1931, got his start in Winnipeg, having met local wrestler Ole Olsen at the gym.

“He more or less started me out in wrestling,” Tomko said of Olsen. “I started working out with him at the YMCA. If you’re good, people notice you, right? That’s it.” Tomko debuted in 1954. Tomko opened the Olympia Wrestling Club in Winnipeg in the early 1950s and trained many local wrestlers. When he left to pursue non-wrestling ventures, the Olympia Club closed down.

But the wrestling ring called him back, this time to Winnipeg’s famed Madison Boxing & Wrestling Club, where he developed into one of the top villains of the era.

“We had a circuit around Manitoba to train these guys, we’d do the small towns so they would learn how to wrestle before they hit the big time,” Tomko said. Piper, for one, used to live in Tomko’s gym basement.

In 1966, Tomko became the Winnipeg representative for the AWA. In early 1967, Tomko was ordered by AWA honcho Verne Gagne to buy the local Madison club as the monopoly on the territory was threatened by impressive attendances at the local club’s cards. Tomko bought the group, then eventually dropped its programming. During his time with the AWA, Tomko served as a mid-card wrestler for the local cards.

A piece in the Winnipeg Free Press on January 26, 1974 by Maurice Smith talked about Tomko. “In 1965 Al Tomko took over the promotional reins at a time when pro wrestling was at a low ebb in Winnipeg but gradually through good matchmaking and promotion, he was able to bring the game back to its present unprecedented popularity,” it claimed, adding that Tomko was named AWA promoter of the year in 1972.

“All I’ve done in the years I’ve been promoting,” Tomko said in the article, “is give the people what they want and make sure they get their money’s worth for their entertainment dollar.”

Al Tomko in Stampede Wrestling. Photo by Bob Leonard

In Stampede Wrestling, Tomko was first Cosmo #1 under a mask, and on his next run, Leroy Hirsch, a play on the famed football star “Crazy Legs” Hirsch.

Central Canadian Championship Wrestling was another Tomko promotion in Winnipeg, launched in 1972.

In 1977, Tomko vacated his Winnipeg home to move on to Vancouver, where he would take up the reigns of All-Star Wrestling. He bought out Sandor Kovacs, leaving Gene Kiniski as a reluctant partner, with Don Owen, the Portland promoter, having a percentage as well.

“Kovacs wanted to get out and he sold it to Tomko. Then to me, his idea of promoting wrestling was different,” said Kiniski. “But then this gets into a business deal, and I’d rather not talk about it. I’m one of these people, my word is my bond. It ended up costing me a big bunch of money because of my stupidity. I trusted people. It just didn’t work out that way.” In the end, his portion was sold to Tomko as well.

The territory was never the same. “Al Tomko killed Vancouver and the whole territory. I worked for Al about four times and he was just lost when it came to wrestling. What a shame, Vancouver was a fine place to work,” once said Bulldog Bob Brown.

Al Tomko comes off the ropes while in Stampede. Photo by Bob Leonard

John Quinn didn’t have a kind word to say about Al Tomko. “Tomko was very much like Otto Wanz. A wannabe. He thought he could wrestle. He didn’t have a clue. He couldn’t wrestle, couldn’t book, didn’t have a clue. He took a territory, we were always sold out within 20 seats in Vancouver every Monday night. When Tomko took over, going over the gate receipts, they went down every week,” Quinn said. “I went to Tomko and said to him, ‘Tomko, you’ve given me a cheque for $360. I spent that on the road.’ He said, ‘John, do you have a trade?’ I said, ‘Yeah, wrestler.’ He said, ‘No, do you have another trade.’ I said, ‘No.’ ‘Well, labourers get $5 an hour.’ I thought, ‘You f****** moron.'”

At his website, DutchSavage.com, Dutch Savage shared his recollections of how the Vancouver territory changed with Tomko’s emergence. “How was it to work for Al Tomko as he slowly killed one of the best territories on the planet? I didn’t want to go up there when he bought Gene, Sandor and Don out, but Don begged me to help him with the book. So for about five months we slowly got the territory going again. We finally got the houses up and a couple of sellouts at the garden and I’ll be dipped if he didn’t book himself with the champion up there and put himself over and take the belt. I wasn’t there that week: no wonder he didn’t want me up there on that Monday night card; he put the strap on his own waist. Don asked me to go back up there several weeks later, and I told him to forget about it. Incidentally, did you ever see Tomko work? ‘Nuff said. Working for Tomko, how do I put this…was like kissing your favorite donkey. Yuk. He was a nice guy, don’t get me wrong , but my granddaughter could out work him. Some of his ideas sounded like a Jerry Springer program.”

Ah, now we’re getting into the colourful stories of Tomko, and they continued right through 1989, when his All-Star Wrestling promotion ran out of gas and folded, despite its extensive television airings across Canada through CTV affiliates. Very little remains of the promotion, as the tapes were reused at the BCTV studios, and Tomko’s stash got trashed. “I had a bunch, but they spoil after a while, dampness, if you don’t store them right,” he said.

“He was a funny guy. He had all these old stories that he’d tell you about a hundred times about his old days working for the AWA and stuff. You’d hear each story about ten times a week,” recalled Michelle Starr.

As for Sgt. Al Tomko, an attempt to capitalize on the popularity of Sgt. Slaughter in the 1980s, when the name was brought up, Tomko just laughed.

Here comes Sgt. Al Tomko!

In a Ring Around the Northwest newsletter interview, Pat Brady talked about Tomko. “A surprisingly well read man, who could discuss almost any topic under the sun. Al Tomko booked me for the first time, September 1985, because I had a car. No bullshit. By the next fall, I’d been involved in three serious wrecks, including one over a cliff in the Fraser Canyon. On two of these occasions, he was more upset about having to cancel shows then about the well being of his employees. Despite his eccentricities and idiosyncrasies, we got along well. I had three runs for him and one thing I appreciated is that he generally have regulars room for artistic freedom.”

Brady then added, “It irked us that he pushed his kids.”

The two sons of Al Tomko were Terry Tomko (The Frog) and Todd Tomko (Rick Davis). Neither really had the size to compare with their father, let alone many of their opponents. Tomko said that both got out of the business long ago. “It’s a thing of the past.” Their daughter, Trisha Kersch, ran the family pet food business.

Tomko and his wife, Mary, had been married since 1960, after meeting at a gym. “You see, my wife was also a figure skater [with the Ice Capades]. She traveled, so she was understanding,” he once said.

Al Tomko, Canadian champion.

For the last two decades, and up until a couple of years ago, Tomko ran Tomko’s Real Bonesproducts (Trademark Pet Products Inc.), a pet foods production company based in Blaine, Washington, where he lived. The dog bones, treats and toys made there were distributed to retailers from Washington to Florida.

Tomko was inspired when his pitbull, Tyson, almost died from choking on a rawhide, and he set out to make a new kind of dog treat that would be safer for his dog to eat. Smoking bones in his backyard let to making them for others, then a true business.

In this writer’s final chat with Tomko, in August 2008, he was, well, himself.

Al Tomko, promoter.

“No derogatory remarks about me,” he said. “I’ve talked to more people that write a magazine, they always throw something in.”

Why do you think you get unfairly judged, Al?

“It’s not being unfairly judged. It’s the people doing the writing don’t know the circumstances, or don’t know exactly what happened. When I talk to you, I don’t tell you everything.

“There’s always two sides to a story, a back and a front.”

He is survived by his wife, Mary, four children, Tanis, Todd, Terry and Trisha, and three grandchildren, Trea, Joshua, and Alexander. Funeral arrangements are pending.

AL TOMKO LINKS

- Oct. 12, 2009: Guest column: I remember … Al Tomko

- Aug. 13, 2009: Oly Olson: Thanks for everything, Al

- Aug. 6, 2009: Al Tomko — a true original — dies