“The Golden Greek” John Tolos, perhaps one of the finest interviews in the history of wrestling, has been silenced. Tolos, a native of Hamilton, Ontario, died Thursday night in Los Angeles. He was 78.

Tolos suffered a series of heart attacks and strokes over the last few years, and shied away from public appearances. His frail condition was in stark contrast to the vibrant, well-conditioned athlete that he portrayed for so many years.

In his heyday, there were few that could talk better than Tolos. It was a gift, and it was spelled T-O-L-O-S.

“Tolos was one hell of a talker. That’s what got him over,” said Art Williams, who refereed and ran towns for the Los Angeles promotion, where Tolos was Americas champion nine times from 1971-80. “Tolos was a better talker than he was a worker — much to his credit, that’s not a knock. That’s what got him over.”

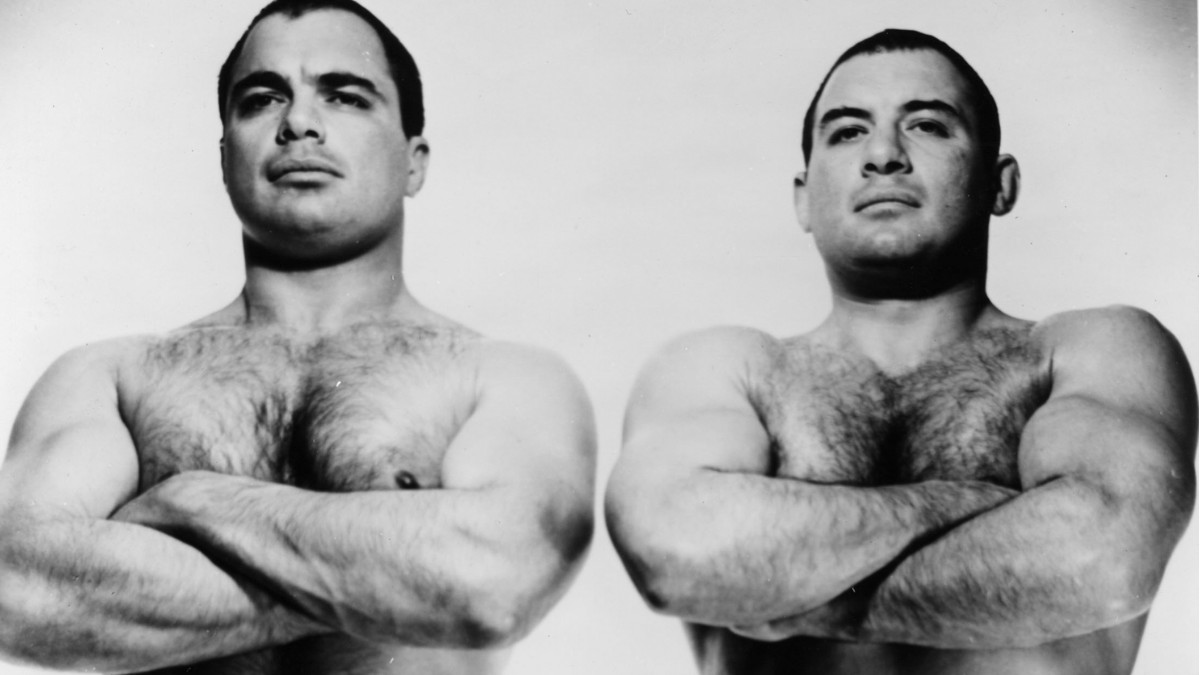

The one and only John Tolos, while on tour in Japan. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

Los Angeles publicist Jeff Walton agreed. “Tolos without a flaw was one of the best talkers ever.”

Frequent opponent Mando Guerrero did his best to put into words what made Tolos the best. “John Tolos was a master at his craft. He actually was from what is now known as the old-school, where he could carry the people to a heated end,” Guerrero said. “John had that, he had that character of his, that mouth, the way he talked. One of the first guys that would carry on an interview that would make you sick, making of fun of people, to capture what ticked the guy off. He was a master at that. He could do it quick. He had that sense of capturing what was good about the guy, his opponent, and know how to use that against him in an interview.”

Tolos had something that could not be taught. “He’s got a personality that when you see him looking around at the people, saying something to the people, the people want to kill him. He’s just got that arrogance to be a good bad boy,” said Jose Lothario. He also had a career that spanned from the advent of television to the international success of the WWF (though his time as a mouthpiece manager in the UWF and WWF is justly forgotten by most). In an interview with Ring Around The Northwest, Tolos said he saw the change approaching. “[E]ventually with all the TVs coming in, everything started to blend together. Every territory started to become the same. Your style got over everywhere. The main thing was your talking. That was the big thing, the interviews, mighty important.”

Never known as a truly great worker — his peers gave him the Golden Potato Award at the 2004 Cauliflower Alley Club reunion for hitting too hard — Tolos had an innate ability to do the right thing at the right time. Tolos once asked Rick Martel to come up with just four highspots for their match. Martel told Tolos his choices, who put them in the order he wanted. “When you go in the ring, ‘Okay, number one!’ He would put it in at the right time,” said Martel. “He wouldn’t go out there and have 10,000 highspots — we only had four. But they were just at the right time, and man, the reaction you used to get out them!”

Growing up in Hamilton, Ont., John Tolos occasionally went to the wrestling matches at the Municipal Pool. But his interest was in amateur wrestling, which led him to the YMCA. His older brother, Tolos, started learning the pro game from “Wee” Willie Davis, so John did too. As an 18-year-old, John toiled at Victoria Cap Co., learning garment manufacturing alongside the boss’ son, and future wrestling colleague, Jack Laskin.

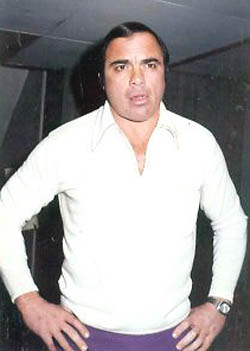

The Tolos Brothers work together on a 1962 card in Niagara Falls, ON.

Hitting the road in 1951, Tolos went to Amarillo, Tex., to really begin his career. For the two decades, Chris and John Tolos were as formidable team as there was, with each willing to fight to the death for the other, “Right brother Chris?” Known as the Wrecking Crew, they fought all the great teams of the day. But like with a lot of brother teams, one shone above the rest; John had the outgoing personality to be a star. “Actually when Chris Tolos went to Canada, when John started going other places, I think that killed off Chris Tolos’s career,” said journalist Bill Apter. “Kind of Rick and Scott Steiner in some ways.”

Like many Hamilton wrestlers, the Tolos brothers were known for their roughness. “They had a tough stomping style,” said Don Curtis in 2004, who often teamed with Mark Lewin against the Toloses in New York State and Florida. “They were pretty much equal in the ring, and really had good timing and thought very much alike.”

The list of tag team titles they held is remarkable: The Pacific Coast belts in 1953; the WWWF U.S. tag titles 1963, knocking off Killer Kowalski and Gorilla Monsoon; the NWA World tag championships in both Florida and Detroit in 1964; the Canadian and World tag belts in Vancouver in 1967; the International belts in Toronto.

In California, John Tolos worked on his tan and ran on the beach, while honing his character into a real maniac, especially in the KCOP-TV studios. He had a string of devious acts that still get the ire up, including breaking Raul Mata’s guitar over his head and losing a Hair Match to Victor Rivera, but then demolishing his foe with a chair after the buzz cut. Tolos would wield 2x4s, chairs and baseball bats, as well as hidden weapons, and even cleared ringside with a boa constrictor.

But it’s his epic feud with Freddie Blassie that cemented his position as one of the greatest heels of all time. It was May 8, 1971, and Blassie was on TV getting an award for being Wrestler of the Year from the fans. Tolos had just won the Americas title from Blassie, and was enraged. “I got hot. There was the doctor’s bag there and I opened the bag and found this powder, he was getting interviewed with his trophy. I threw the powder, I threw a lot of powder,” Tolos told RATNW. “I got his trophy and hit him over the head with it. We had a riot, had a riot in the studio.” Blassie had been hit with Monsel’s powder, and screamed “My God, my eyes!” The fan favorite was taken to South Hoover Hospital, where Dr. Bernhart Schwartz, the state athletic commission physician reported, “It is problematic how long he will be out. The injury takes several months to heal. I recommend that he retire, but I doubt that he will.”

Of course it was all an elaborate work by L.A. promoter Mike LeBell and his bookers Jules Strongbow and Charlie Moto. But what a work. Blassie knew enough to stay out of the spotlight as they built to an epic showdown in the mammoth Los Angeles Coliseum on August 27. Walton feared the planning was too far out. “It was so far, far away. I thought, ‘My God, so many things could go wrong and here I am doing the poster for this thing.’” The office totally stacked the card at the Coliseum to protect itself.

The promotion smartly kept them apart. Blassie would show up unexpectedly at shows, screaming for Tolos’ head, his eyes still bandaged. “They never touched each other. They’d come close. You’d see cops coming and grabbing Blassie and straining to hold him back,” said Walton. Tolos’ car was badly damaged outside an event in Bakersfield. “We didn’t expect the amount of heat we’d get. He had to get extra protection; we had to hire extra protection.”

When Blassie and Tolos finally met, it resulted in a crowd of 25,847, paying $5-$7 for a live gate of $142,158.50. “The paper said it was 25,000 but it looked like 35,000 to 40,000,” said Tolos. “It was a hell of a big, big, big card.”

Walton was able to reunite Blassie and Tolos on his WrestleTalk radio show on February 7, 2003, just months before Blassie’s death. Tolos was at his boastful best. “We had the greatest feud in professional wrestling. You tell that to any fan, what was the greatest feud, and they’ll say Blassie and Tolos. It was all kinds of matches, it wasn’t just one fall, or two out of three. It was great super, vicious matches like the cage match, like Texas Death matches, Indian Death matches, stretcher matches where there had to be a winner, where there had to be a winner. The hand had to go up. Those were vicious, vicious matches. There’s no question about it, Blassie was one of the greatest wrestlers that I’ve ever wrestled and I’ve ever known. I am the greatest, so he was one of the greatest.”

Blassie, no shrinking violet on the microphone, quipped back. “Top to bottom, you were, without a doubt, my toughest opponent. I’m saying this just because you’re there, but every time I was matched up with you, I knew I was in for a hell of a night. And I’m telling you, too bad we didn’t get paid!”

When his in-ring career ran down in the 1980s, Tolos stayed out of the business for a while in California before being lured back as a manager of Cactus Jack (Mick Foley) and Bob Orton Jr. in Herb Abrams’ UWF promotion. He would follow that with a brief run in the WWF as ‘The Coach’, with “Mr. Perfect” Curt Hennig as his main star.

After finishing wrestling, Tolos worked at Guy Martin Honda Oldsmobile in Woodland Hills, Cal. His only son, Chris, lived nearby, as did his ex-wife of 20 years, Ingrid.

In August 2006, Tolos talked about how particularly moved he was by the show of concern following his stroke, and claimed he heard from friends “night and day”, as he “met so many people through the years.”

He admitted that he missed the spotlight. “Oh yeah. I wish I was still there.” He also misses departed friends, and especially, his brother Chris, who died in November 2005 of cancer. “I liked being despised. That was it for me. It’s very big. Even as I think about the guys I wrestled, it was really, really good stuff, good guys.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: A large portion of this obituary comes courtesy The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels, by Greg Oliver and Steven Johnson.

RELATED LINKS

- Aug 13, 2005: Chris Tolos dies of cancer

- May 31, 2009: Let the John Tolos stories roll!

Greg Oliver met John Tolos at numerous Cauliflower Alley Club reunions, and there were few that looked more dapper and happier to be there than The Golden Greek. Greg can be emailed at goliver845@gmail.com.