If there is one feeling that you get when you read through Slam Wrestling’s archives, it’s that the wrestling business is full of incredible highs, but also torturous lows. For all the adulation, there’s a hefty price pay, a price which was recently explored in the movie The Wrestler, which earned Mickey Rourke a Golden Globe award for Best Actor, though controversially, not the Oscar.

Roddy Piper speaks at the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame banquet in June 2008. Photo by Greg Oliver

One man oft-mentioned by Rourke in interviews about the film, was “Rowdy” Roddy Piper. Piper, of course, embodies the highs and lows of professional wrestling, and is a veteran in Hollywood too, with roles both big (They Live) and small. When he spoke to Slam Wrestling about the film, and about how it really was true to life for some wrestlers, it was clearly a highly emotional experience for him.

“As someone who has been in the business for a long time, I don’t mind saying that the movie really got to me,” Piper said. “I had the chance to speak to Mickey, and I told him, ‘I don’t know what kinda research you did, but you hit the nail right on the head.’ What stood out to me as a wrestler was that at no time did that character ever get physical outside the ring. And that’s very typical; most of us are pretty soft outside of the ring.

“But even more so than that, the thing that probably grabbed me the hardest was the way it ended. All my brothers (wrestling peers) are dead, man. So, at the end, it caught me because it just went to black, and that’s how it happens in our world. Look at Curt Hennig (who died in 2003 due to cocaine intoxication) — he was the picture of health. And boom! Black. Not fade to black, just black. I’ve been to so many funerals.”

A strong theme in the film is that wrestling’s mortality rate amongst its high-profile performers is staggering in comparison to that of any other athletic endeavour. A study in the wake of the Benoit tragedy showed that 104 professional wrestlers under the age of 40 had died in the period 1997-2007. Forty of those were full-time professionals, who would were well-known to anyone who had followed the sport for even a short time.

“Thinking about the friends, the brothers I’ve lost, makes me feel lonesome. I lived with these guys, literally. I wonder why no-one on the outside catches on to what’s happening? I guess it’s because they don’t care.

“Can you imagine what would happen if four Manchester United players died, all in separate instances?” Piper continued, using a European analogy as he prepared to visit the continent with his daughter. “Or if a soccer player killed himself, how much attention it would get? People would wonder what on earth is going on, and there’d be an investigation. But there’s no investigation for these guys. When a professional wrestler dies, sure, they do an autopsy, but then they shuffle them on.

“In professional wrestling, we’re always making contacts, finding a chemistry. Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier had a chemistry. Roddy Piper and Hulk Hogan had a chemistry. Roddy Piper and Ric Flair had a chemistry. That’s the reason these people drew money together. But you can’t put all those chemistries in one room, and then start killing every second one. When someone you were that close with dies, it’s part of you that goes, too.”

The high death rate among professional wrestlers is made all the more poignant by the fact that a large percentage of them are due to heart attacks, believed to be caused largely by the use of steroids, which not only enhance muscularity, but the body’s internal organs, too. This practice is also alluded to in the film, as Rourke’s character suffers a heart attack, but even though he has an emergency bypass operation, continues to wrestle and even uses recreational drugs. Piper has seen the damage that all kinds of drugs — performance-enhancing, painkilling, and recreational — have done to wrestling’s performers, and notes that when he wrestled, such activities were close to a necessary evil.

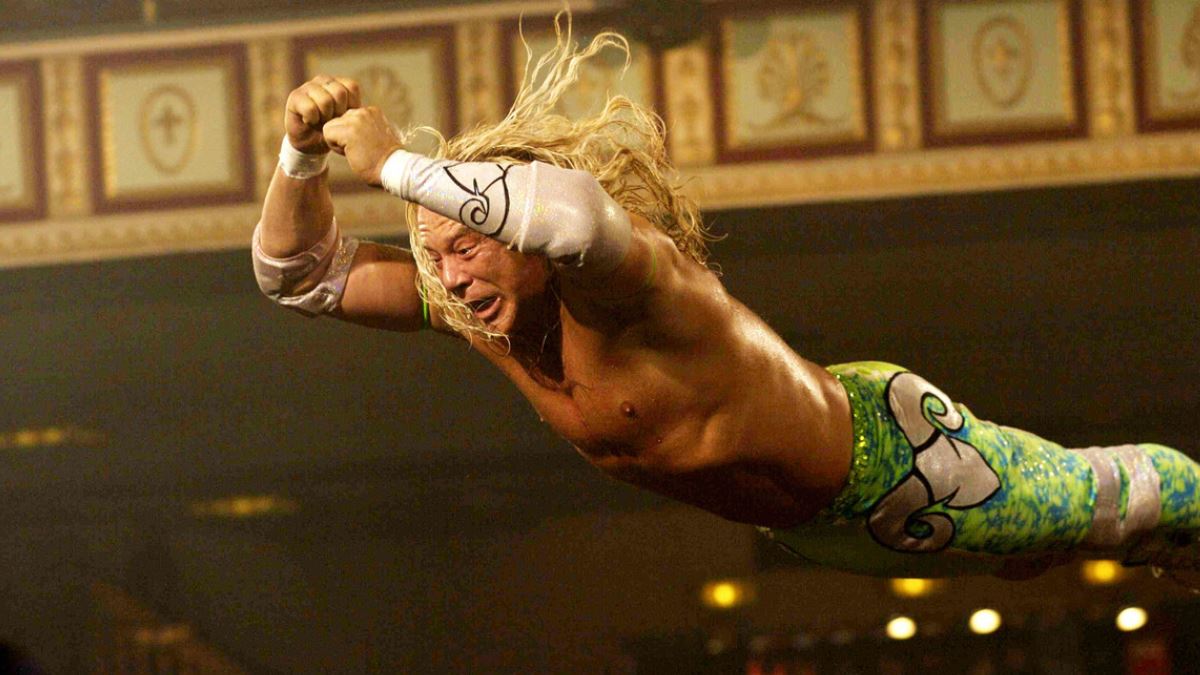

Randy “The Ram” Robinson takes a smack from The Ayatollah (Ernest Miller) in The Wrestler.

“It’s a little different for the wrestlers today, but the schedule I had to keep left you not knowing who you were,” said the 54-year-old. “In 1991, I did an afternoon show in Manchester, England, and an evening show in the same building. Then, I got on a plane from Manchester to Heathrow, and Heathrow to Connecticut. I went in and did five hours of voiceovers for television. Then I got on a plane to Alaska, wrestled there, flew back as far as Seattle, and then I rented a car and drove 160 miles home. And that was all in one loop, without a break.

“It’s tough to make that route without a shot of whiskey,” he continued, using the drink as a nom de plume for other substances. “I can recall being in Pittsburgh and being dragged out of my bed at 11 a.m. to go and kick off 60 interviews for television, and only then could I go back to my bed. So imagine the time-zones; the stop-start, quick, let’s go kinda life. It’s very difficult do these things, and be on at the same time.”

Perhaps of all the overall themes of the movie, the most poignant is that of the lead character, 20 years past his prime but still having had success while at the peak of his powers, cannot afford to pay his rent, even while working at a deli during the day, and wrestling on weekends. For in the real wrestling world of WWE, there is no pension plan for its performers, who are labelled as independent contractors; Piper’s recent appearances on Monday Night Raw and expected WrestleMania 25 gig are paid on a per night basis. For those full-time WWE employees, it is understood that bookings for other companies are out of the question despite their “independent” status. A recently-dismissed lawsuit by three former WWE wrestlers brought this matter into the spotlight, and has noted that while the office staff at the company are entitled to the benefits in later life, the wrestlers are not. In turn, this has led to oft-heard calls for a wrestler’s union to finally become a reality.

“You know, wrestling today really just means the WWE, and they’re the only ones that could afford to do something like this,” Piper said with an air of sadness. “The WWE have done some wonderful things for wrestlers. But we can’t keep on dying. The wrestlers give their hearts — they give the best part of their lives. So as the success goes on, why aren’t they being taken care of?

“My generation and the generation before me — these guys today shouldn’t have to go through what we went through. They’ve got masseurs and therapists now, whereas to save money on the road, we would’ve ordered old pizza if we could. So we’ve taken the pain. I just think, ‘C’mon guys, if it’s a billion-dollar business, which it is, give it (a union) to them.’ But wrestlers are afraid for their jobs, so it’s probably only going to be pressure from the public that makes it happen.”

A young Roddy Piper. Photo by Terrance Machalek

Be that all as it may — the drugs, the schedule, and the losses — Piper’s energetic tones, which only change with these more sombre recollections related to the film — show that if it could be true of anyone, Piper was born to be a professional wrestler. In fact, he believes the wrestling lifestyle may have had the opposite effect on him, than it did for others; whereas some crumbled in the face of wrestling’s harsh realities, the business gave him something to cling to.

“Before I got into wrestling, I wasn’t going anywhere with my life. I was 15 years old and living in a youth hostel. I was an amateur wrestling champion, a Golden Gloves boxing champion, and I [later] earned my black belt in judo from Gene LeBell, but I didn’t know what I was gonna do with my life,” Piper said, continuing the story that has become folklore. “Then, I was at a wrestling show at the Winnipeg Arena in Canada, and one guy didn’t show up. So my amateur wrestling coach, who was a professional wrestling referee, said ‘I can get you $25.’ I didn’t know anything about professional wrestling, but I went in there and had probably the shortest match in the history of that arena.

“After that, I kept wrestling for the money. I went from doing nothing, to working as much as I could. It was the only kind of economic entity that I could cling to at the time. There were no questions asked; all that the other wrestlers asked was that you gave 100%.

“They were last of the Gorgeous George-era guys, who were finishing as I started, and they were really bitter about the business. But to me, they were great Dads; if you ever needed to learn how to take care of a family, or any advice, you had 300 miles driving in a car to listen to them. Wrestling gave me a shot — I had to get on the field at some time in my life. For that, I’m eternally grateful.”

The end of The Wrestler leaves open for interpretation the fate of Randy “The Ram” Robinson, and if life imitates art, in a similar way the destiny of professional wrestling current combatants is as of yet unknown.

Fans can only hope that more of them find the rewarding life in wrestling that Roddy Piper did, and not the pitfalls that befell Davey Boy Smith, Hercules Hernandez, Curt Hennig et al.

Author’s note: Following this interview, Roddy Piper asked that we send a shout-out to Freya Miller.

RELATED LINKS

THE WRESTLER (2008) LINKS

- June 17, 2009: The Wrestler still resonates with Ring of Honor

- Feb. 23, 2009: Analysis: Rourke’s predictable loss at the Oscars

- Jan. 20, 2009: Associate Producer of The Wrestler documents wrestling’s killing fields

- Sep. 17, 2008: Aronofsky and Rourke passionate about The Wrestler — and wrestling

- Sep. 11, 2008: Aronofsky’s The Wrestler an instant classic