Several months ago, I was tasked with putting together the Frenchy Roberre story after the popular wrestler died in Portland, Oregon. Thanks to many knowledgeable sources, I was able to pen a credible and newsworthy story: Frenchy Roberre was a fan favourite.

One interesting aspect that surfaced while researching the Roberre story was the emergence of another wrestler who used the name Maurice Roberre. The story became all the more intriguing because the name Roberre was actually a derivative of the more famous Robert name which was popularized by the legendary former world champion Yvon Robert. Compounding the issue was the fact that Yvon Robert also had a younger brother in the game named Maurice Robert. Several decades later, of course, Yvon’s son, Yvon Robert Jr., would enter the scene in Grand Prix Wrestling out of Montreal.

Mat historians who are heavily engrossed in researching wrestling’s often puzzling past will readily understand that promoters and wrestlers took generous license with the use of names for various reasons, the most common of which was for gate appeal.

Promoter Jack Pfeffer used a string of names for his wrestlers that were very similar to the names of established stars. Fans had to do a double take to be sure whether or not they were seeing the real McCoy.

As is so often the case after an initial story is published, so many additional facts and anecdotes come to light that it is almost obligatory for the writer to bring readers up to date. So in the interest of historical clarity, I will attempt to resolve the Robert-Roberre dilemma with as much finality as wrestling’s most dangerous finishing hold.

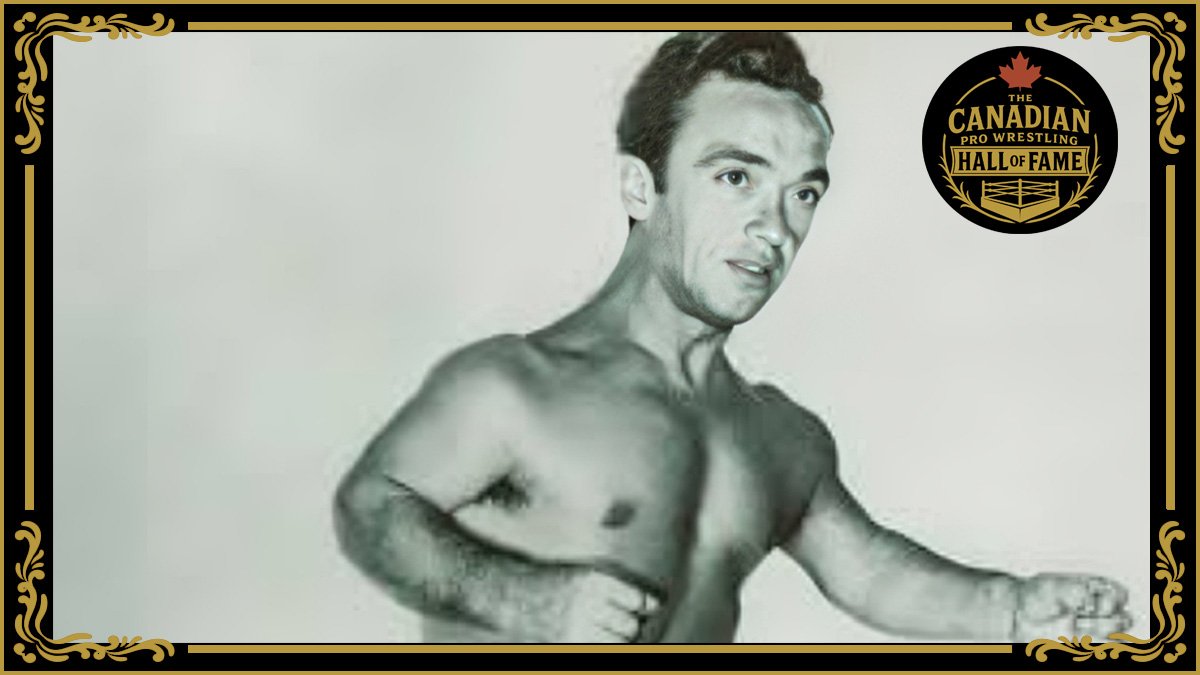

The great Yvon Robert burst upon the scene in the mid-1930s and in quick order established a solid reputation. At the height of his fame, he became a Quebec folk hero, rivaling hockey star Maurice “The Rocket” Richard as the most popular sports figure in Quebec.

Robert was a mainstay at the Montreal Forum for promoter Eddie Quinn but also headlined cards throughout North America. I first became familiar with Robert in the early 1950s after reading newspaper accounts of his exploits at the Ottawa Auditorium. Quinn promoted Ottawa as part of the circuit and brought in the top names of the day. Sooner or later they all faced Robert including Wladek Kowalski, the Great Togo, Lou Thesz, Honest Johnny Valentine and the Duseks from Omaha. Others who made appearances were Don Leo Johnathan, Manuel Cortez, Bobby Managoff and the show stopper, “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers.

Robert was to French Canada what Whipper Billy Watson meant to English Canada and the pair often teamed together as well as opposing each other in singles matches.

Robert also teamed with Larry Moquin and Johnny Rougeau against the top teams. It was always the intention to groom Moquin and Rougeau as his successors but those plans were slightly altered when the acrobatic Edouard Carpentier arrived on the scene and became the new favourite among francophone fans.

Yvon Robert retired in the late 1950s and died in 1971 at the age of 56. His younger brother Maurice Robert was also in the game at one time but never achieved the status of his more famous sibling. According to sources, the younger Robert never quite reached stardom nor was he a force in the wrestling rings, preferring to work locally in the Quebec area.

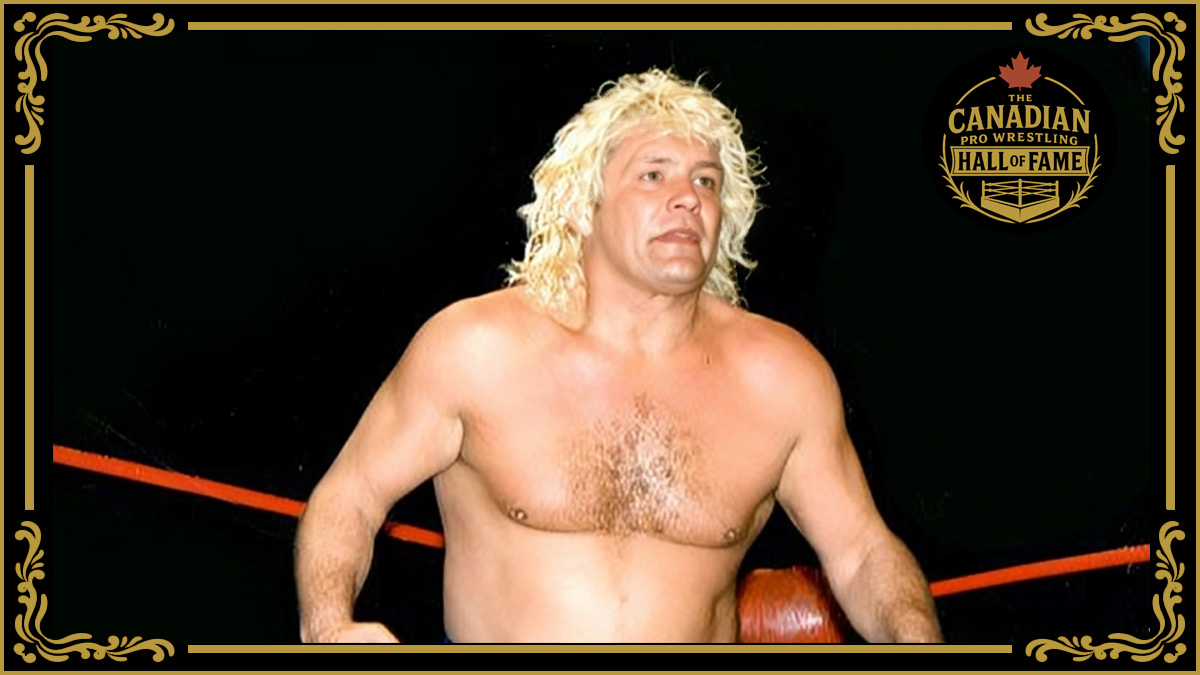

In the 1940s a young wrestler named Maurice Boissy was breaking into the game and quickly adopted the name Maurice Roberre, no doubt to take advantage of the popular Robert name at the time. His career is also an interesting study.

According to his son Gerard, the family moved to the Chicago area where his father pursued his ring career.

“My mother Eveline was also trained as a wrestler and traveled with my father throughout the U.S… She worked under the name of Miss Atlas, Girl Wrestler and along with my dad were a very unique husband and wife team.” The younger Boissy remembers a lot of his father’s contemporaries including Mad Dog Vachon and Verne Gagne.

“I know my dad wrestled all over the U.S. and Canada, plus Cuba and Venezuela. During his time as a wrestler he joined the Chicago Police Force. He retired after 25 years of service,” Gerard recalled. “The Chicago Tribune called him the Wrestling Cop.”

During Roberre’s career, the family moved from Chicago to Spooner, Wisconsin. Roberre retired from the ring in the early ‘60s but whipped himself back into shape and resumed his career for another year or two before finally calling it quits in 1969.

“My friends and I would go watch him. It was pretty cool,” Boissy recalls fondly.

Finally, Maurice Roberre retired completely, remarried and moved back to Quebec, out in the country near Shawinigan. He died in April, 2007.

“I would visit him most summers,” concluded his son. “He lived in a beautiful little town and was happy living near two of his brothers.”

When I began researching the career of Frenchy Roberre I quickly discovered that his real name was Yvon Losier before he adopted the surname Roberre. Although he also worked under his real surname of Losier in the Martimes it was as Yvon “Frenchy” Roberre that he made his mark and is best remembered.

Born in 1930 in New Brunswick, he was well traveled and seems to have struck most acquaintances as an easy going guy with a good French-Canadian sense of humour and a photogenic memory.

He earned his ring scars in Northern Ontario, the Gulf Coast and in the Pacific Northwest where he finally settled in Portland after he retired.

Life-long wrestling observer Art Nelson has vivid memories of Roberre. Nelson has been watching the game for almost a half-century and was in Portland the night promoter Don Owen tagged the fierce Maurice Vachon with the “Mad Dog” monitor. He has retained those treasured memories when you could meet wrestlers face to face around town or at the arena without fear of being impeded by security guards.

“When Frenchy decided to stay in Portland, he took up bricklaying as a profession,” Art recalled. “So large were his hands that he could pick up two bricks with one hand. He used to say bricklaying was so much easier when you had that advantage.”

Roberre was also part owner in a local tavern called “Frenchy’s Villa” and had a musical side to him.

“He was quite skilled at playing the spoons,” Nelson continued. “He would often show up at a local pub and give an impromptu performance but not with ordinary tablespoons. Rather, because of his large bear paw-like hands, he would use a pair of 18-inch wooden salad spoons and play them to perfection.”

While a wrestler’s career can be fondly remembered by fans and dissected by historians, it remains for family members to give a truly insightful look.

“I have so many memories of wrestling matches over the years,” stated Frenchy’s daughter Annette. “Many times as a child, we would have wrestlers as our guests. My dad always opened his home to them. The midgets used to tend bar for him when they were in town. They would run up and down the top of the bar serving beers. Later they could be found under the bar after some beers were consumed.”

His humane side was evident when he volunteered once or twice a week to deliver food to the hungry at soup kitchens. He believed no one should ever be hungry. Friends he had known in the 1950s always received a Christmas card from him.

Later in life he was diagnosed with diabetes which eventually resulted in the amputation of one leg.

“Even this didn’t slow him down,” laughed Annette, “or dull his sense of humour. He would joke about putting on his prosthetic backwards to kick his own butt.”

For the last three years, Frenchy lived in an assisted living facility, surrounded by his wrestling memorabilia and often giving visitors a tour and a good dose of his humour. He died in hospital from complications due to a fall he took out of his motor chair. A broken rib led to more severe illnesses that claimed his life on July 13, 2008.

“I had him cremated,” concluded Annette. “I will bring him back to his hometown of Tracadie, New Brunswick next summer to be buried.”

Some of Frenchy’s ashes will be spread over the Gorge in Oregon where he did a lot of work and camping. He once received a plaque from the State of Oregon for his work on the restoration of the scenic highway up to the gorge.

He was not the biggest of stars in the wrestling ring but to his friends and family he was bigger than life.

To his daughter Annette: “He was the biggest man ever in my life.”

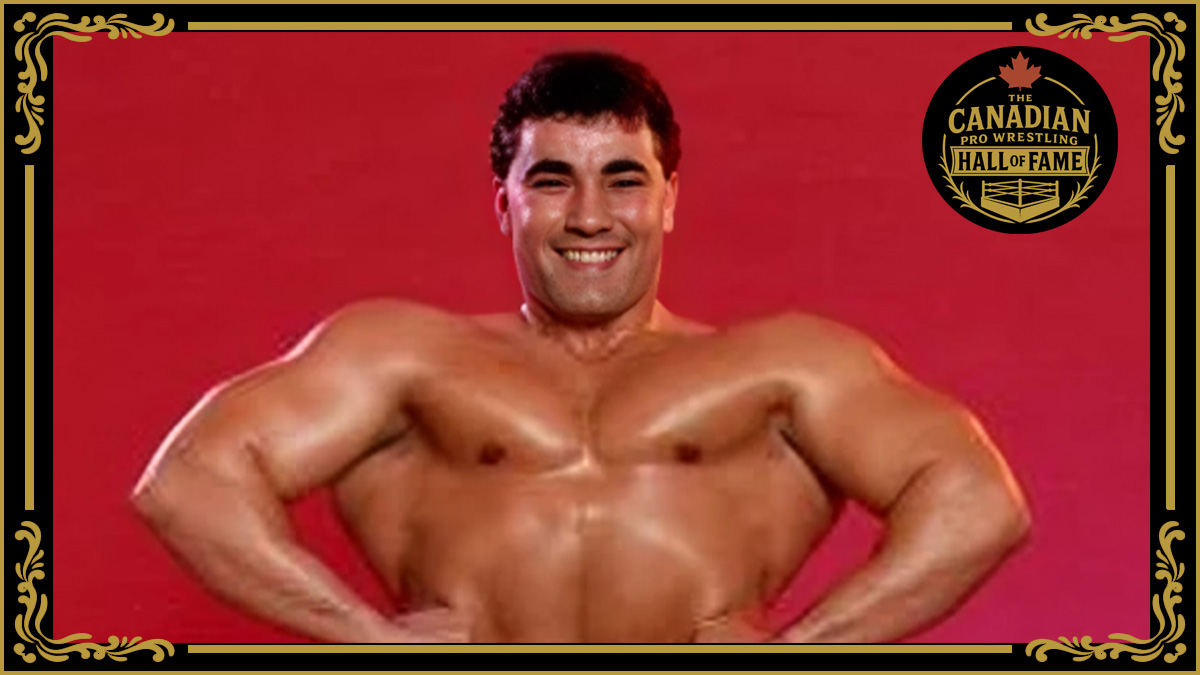

Yvon Robert Jr. may have had similar sentiments when he followed his father, Yvon Robert Sr. into the pro ranks. Yvon Sr. was the biggest star in Quebec wrestling in his time and the emergence of Yvon Jr. to the mat wars kept the Robert legacy alive.

Not only was the younger Robert a successful wrestler but along with Paul Vachon, they revitalized wrestling in Quebec when they formed Grand Prix in 1971, the same year Yvon Sr. died. Most memorable televised match I recall was a slugfest between Yvon Jr. and partner Edouard Carpentier against the Hollywood Blondes, Dale Roberts and Gerry Brown. The bout typified the Grand Prix style of knock ‘em down, drag ‘em out action that captured the imagination of the wrestling world in that era.

The promotion perked up interest for a short period but in the tired and turbulent times soon disbanded and Yvon Jr. quit the business entirely in the late 1970s.

The Robert-Roberre saga remains one of the more interesting and intriguing wrestling stories, not only because it showcased the rich talent that came out of Quebec but also because it underlines the distinctiveness of the wrestling business in general.

In the kayfabe era, nothing was ever as it seemed and it could never be for certain that everyone was really who they said they were. Promoters and wrestlers delighted in keeping fans guessing in the wacky and whimsical world of pro wrestling.

Whether it was Yvon Robert Sr. or Maurice Robert or Yvon Robert Jr., or Yvon Roberre or Maurice Roberre, when the opening bell sounded all was forgotten by the fans save for the action in center ring.

Everyone concentrated on the evening’s matches; it was preferable to leave others worry about the intricacies of the game.