“Every day, these guys are dropping off like flies. Something has to be done!”

— Darren Aronofsky

Darren Aronofsky and Mickey Rourke take pro wrestling seriously, a distinction that sets them apart from the rest of Hollywood, and even some wrestling companies that continue to hire comedy writers for their Creative departments. In the critically acclaimed new film The Wrestler, every scene is a testament to director Aronofsky and star Rourke’s determination to make a serious, thoughtful, and sober film about the ridiculed subculture of pro wrestling.

In a film industry where the last mainstream release to prominently feature pro wrestling was Jack Black’s slapstick farce, Nacho Libre, the fact that Aronofsky was able to get a movie that profiles the wrestling industry with as much depth and insight as The Wrestler made is less an anomaly than a miracle.

“There’s a whole genre of genre of boxing movies — thousands of them — but no has ever done a serious film about wrestling,” says Aronofsky, the director of visionary films like Pi and Requiem For a Dream. “No one has ever shown the true life of a wrestler in a fiction film. A lot of people out there think wrestling is a joke and they don’t realize that it is a true athletic activity. The more I started to research the world, the more I discovered that it was a very unique universe that no one had seen on film, and that it would be [important] to bring this to the world.”

Some might question the effectiveness of a fiction film covering these problems versus a documentary, like Beyond the Mat. But by using a fiction film, one suspects that Aronofsky knows he can reach a larger audience.

The influential Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein was known for using fiction films to try and enact social change, calling his filmmaking style a “Kino Fist.” While not as preachy, by opting to address the grave iniquities of the pro wrestling business with a gripping drama like The Wrestler, Aronofsky has developed his own “Kino-Fist” to fire a heart-punch into a society that has chosen to turn a blind eye to the suffering of these “underground American heroes.

Sitting down with Rourke and Aronofsky for an interview less than 24 hours after The Wrestler‘s North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, they reveal that while they both have come to admire and respect professional wrestlers, initially Rourke was dubious about the project.

“I did not have an attraction to it, coming from a boxing background,” says the Hollywood veteran. When Aronofsky brought the script to him in Miami, Rourke says, at first he did not quite understand it. But Aronofsky’s impressive resume and passion for the project convinced him to make a leap of faith — with a little help from a wrestling legend.

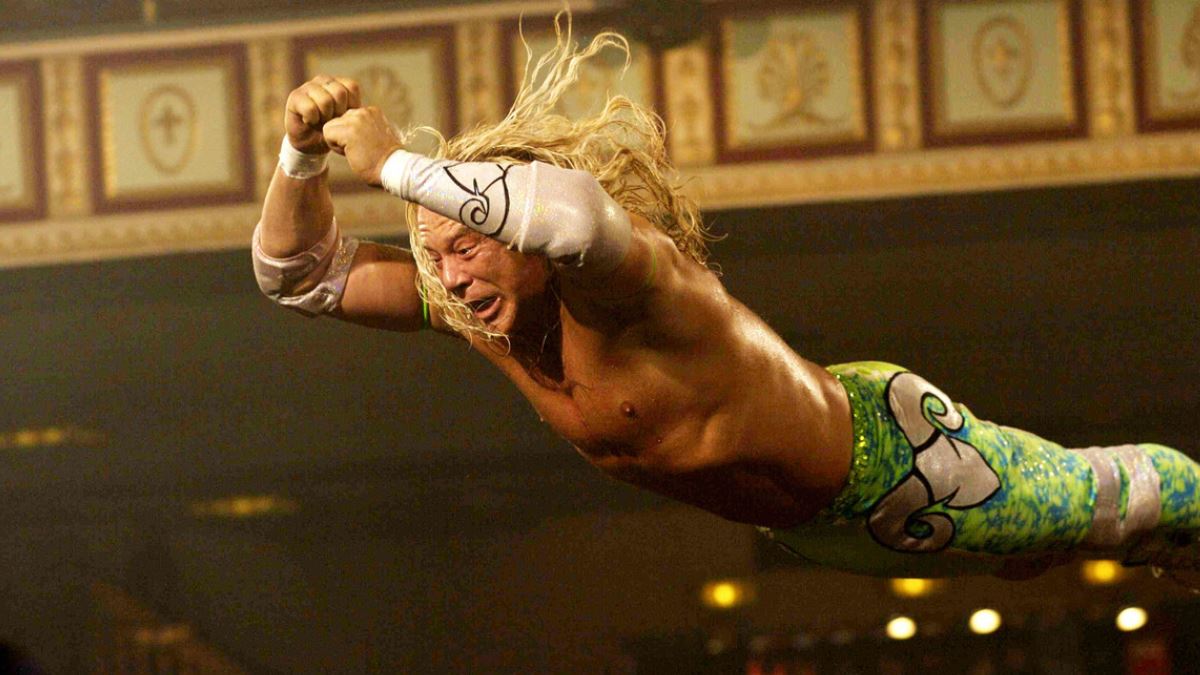

Rourke began to research professional wrestling from the ground up, beginning with meeting wrestlers. While some might think that a Hollywood actor approaching the role of a pro wrestler would model himself after someone like a Ric Flair, Rourke’s major inspiration for the role of “The Ram” came from Greg “The Hammer” Valentine, an unsung veteran of the business and gifted worker. It’s tempting to assign Rourke’s attraction to Valentine to their parallel career paths: they are both formerly hard-living, timeworn, and unappreciated journeyman professionals with limitless talent who are generally seen as never reaching their full headliner potential.

“Greg ‘The Hammer’ Valentine was this big, big guy in, maybe, his early 60s, but he was still all tanned [like he was in his heyday], and with all this long blonde hair,” Rourke says with undisguised admiration. He said this “older wrestler” still maintained a sense of dignity about him, and that impressed him a great deal. “He spoke about wrestling with such enthusiasm, and such pride,” Rourke explains, that “The Ram” character came to life for him. After the unforgettable impact Valentine made on Rourke, the actor decided that The Wrestler was a project worth developing.

With Rourke now on board, production on The Wrestler began with Aronofsky at the helm. Both men discovered many inconvenient truths about the wrestling business along the way. First and foremost was the toll that wrestling takes on the human body, which Rourke discovered firsthand while training at Afa the Wild Samoan’s famed wrestling school. “I kept getting hurt,” Rourke says, simply learning and executing the wrestling moves. When he spoke to other wrestlers, he found out that they experienced the same kind of pain on a regular basis. But where Rourke’s experience differed, he discovered, was that he had constant health care, while they did not. He winces when recalling his pain: “I had three MRIs in two months. Most of my free time was spent in doctors’ offices or making excuses to Darren [Aronofsky] why I couldn’t come to work.”

Disturbingly, Aronofsky and Rourke realized that actual working professional wrestlers are very rarely given the option to take time off to heal their serious, life-endangering injuries. To these unionized Hollywood vets, business practices in pro wrestling are shockingly primitive and cruel; they say it shocked them to discover that most wrestling promoters don’t hesitate to fire any wrestler who attempts to leave the road to recuperate his injuries, and that, as independent contractors, the wrestlers themselves by and large have to pay for the doctor visits required to treat the injuries they incur on the job. Both Aronofsky and Rourke developed such a respect for the courageous men who risked their bodies with no safety net and no support system that The Wrestler took on the qualities of a labor of love.

One such wrestler they encountered during filming was the hardcore icon, Necro Butcher. As they saw what Necro Butcher put his body through, and discovered from him and his colleagues how little financial compensation and practical support he received in return from wrestling promoters, they were deeply moved. Both Aronofsky and Rourke put Necro Butcher over with no hesitation. “Necro Butcher is a cult phenomenon,” says Aronofsky, “He’s a great, American underground hero.”

Mickey Rourke, himself a great, underground hero in a different corner of American pop culture, seemed personally insulted that wrestling promoters would not take better care of Necro Butcher. Still indignant that this “great American hero” was not provided with any health care or protection in his career as a pro wrestler by the promoters, Rourke recalls a bittersweet moment he shared with Necro Butcher. “And what did he say after the movie was finished? ‘That was my life!'” says Rourke in disbelief that such a talented wrestler could live such a hard life. “[Necro Butcher] cried when he read the script,” adds Aronofsky.

In the process of the interview, both men reveal that they are incredibly well versed with the goings on backstage at the major American wrestling entertainment companies. When discussing how Necro Butcher deserves better, Rourke brings up another man who he says should be a star today: independent wrestler Tommy Faria, who trained Rourke for the film.

“He is 5’10”, 215 pounds, which somehow doesn’t qualify him to be a star in the WWE,” Rourke says, referring to that company’s long standing policy of favoring wrestlers who are extremely tall and excessively muscled. As if lecturing, Rourke then lifts his finger, and declares, “But let me tell you something right now: there’s maybe just five guys that can do what he can do! That’s another problem [in the wrestling world]: politics.”

After considerable research, the two Hollywood outsiders concluded that politics keeps the best wrestlers from making a living in the top wrestling companies. Aronofsky quotes Tommy Faria, who said that “Mickey [Rourke] was better than 80% of the [talent roster] in the WWE,” and infers that, were he not a star, they would probably have no interest in Rourke, regardless of his obvious talent.

The conversation then turns to how their film is very close to reality, and the dark subject of the many deaths that have occurred in the world of professional wrestling. When asked whether the wrestling companies should self-regulate themselves, or if the federal government should intervene, the soft-spoken voice of Aronofsky takes on a much louder, more passionate tone:

“The [U.S.] Department of Labor should look into them. The wrestlers should be unionized. They should absolutely be unionized! The fact that they’re entertainers and athletes — doing both things — they need to be able to take care of themselves. None of them even have pensions!”

Rourke agrees that the Labor Department should immediately get involved in investigating the top American wrestling companies. “Absolutely, these [wrestling promotions] should be looked into … there’s no insurance, no pensions!” Rourke barks with unfeigned emotion in his voice. He speaks of the injured and dead wrestlers as if they were his brothers and, in a way, they are, as he joined the fraternity of wrestlers for a number of months. He will also likely be remembered as the actor who delivered the most realistic and passionate portrayal of a wrestler in film history.

“On one of the last days of shooting, ” Rourke remembers, “We saw a picture of this guy with a fantastic build, a lot of charisma. And I said “let’s Google him.” I don’t know how to Google, so he [Aronofsky] Googled him. What was his name?”

Aronofsky says, “Lex Luger.”

Rourke continues, “Yes. And you know where he is right now? Crippled. That’s how it is, and that’s troubling!”

When, in the interest of balance, it is mentioned that some wrestlers have made it big in Hollywood, and that there are some other success stories from wrestling, such as Jesse Ventura becoming Governor of Minnesota, Rourke slams his hand on the desk and takes great offense to this statement: “The majority of wrestlers don’t end up like Hulk Hogan or The Rock!” he exclaims. “They end up like this guy, Lex Luger.”

An uncomfortable silence ensues as everyone pauses to reflect upon all of this. Once everyone’s composure is regained, they are asked how they would respond to those who argue that wrestlers should not be unionized. Aronofsky counters with, “They throw their bodies around the ring and they wear their injuries for a very long time. People [who question that they need unions] can call it fake. But falling off the top rope to the ground — you show me anyone, any 20 year old, any 30 year old, any 40 year old, that does that and doesn’t wake up with bruises…”

“No, you’re going to the hospital!” Rourke finishes Aronofsky’s thought. “I went through it.”

Rourke then leans back in his chair and looks pensive, as he sadly reveals that the man who he bases much of his performance on, Greg “The Hammer” Valentine, is also one of those permanently incapacitated wrestlers. In one of wrestling’s great ironies, the man known as the Master of the Figure Four Leglock is nowadays “only walking with much difficulty” because of years of wear and tear in the ring, according to Rourke.

Despite the film shooting being over, and both men moving onto different projects, they are not abandoning the cause of wrestlers. They have been so deeply affected by the alarming number of premature deaths of wrestlers, and the easily preventable reasons for the death toll, that they continue to investigate this world that produces so many heroes, and yet so much tragedy.

Aronofsky says with great concern, “The fact that the mortality rate, the disability rate, and the fact that there is no safety net for these entertainers is tragic. And that’s why guys like Eddy [Guerrero] had tragic ends. I mean, every day, these guys are dropping off like flies. Something has to be done!”

Rourke reveals how well read he is on the topic already, and it is clear that would be able to debate the topic of professional wrestling with the top experts in the field. “We’ve talked to lots of wrestlers about this, and I’m even reading books about them. The next ones I’m interested in reading are ones I’ve heard of called Ring of Hell [by Matthew Randazzo V], and the [Bret] Hart book. I mean the story of [Chris] Benoit is just heartbreaking. He lived for wrestling, was on the top tier, and they moved him down, just like that.”

He concludes, “I wasn’t aware of how hurt these guys get after their day in the sun is over. I mean these guys, even in their 40s, can barely tie their shoes, and the reason is that they feed off the adrenalin of the crowd, and they go beyond what they should for safety matters. This is entertainment, but it’s entertainment with consequences.”

As the publicist informs them that their time for the interview is up, Aronofsky says that he hopes his film will not just be viewed as a work of art, but as something that precipitates change in the wrestling business. His passion is obvious, and as he walks away to his next interview, one could see that he still feels touched by the discussion of the maimed and the dead.

THE WRESTLER (2008) LINKS

- June 17, 2009: The Wrestler still resonates with Ring of Honor

- May 23, 2009: The Wrestler ‘really got to me’: Piper

- Jan. 20, 2009: Associate Producer of The Wrestler documents wrestling’s killing fields

- Jan. 11, 2009: Mat Matters: A Golden Globe for all wrestlers

- Sep. 17, 2008: Aronofsky and Rourke passionate about The Wrestler — and wrestling

- Sep. 11, 2008: Aronofsky’s The Wrestler an instant classic