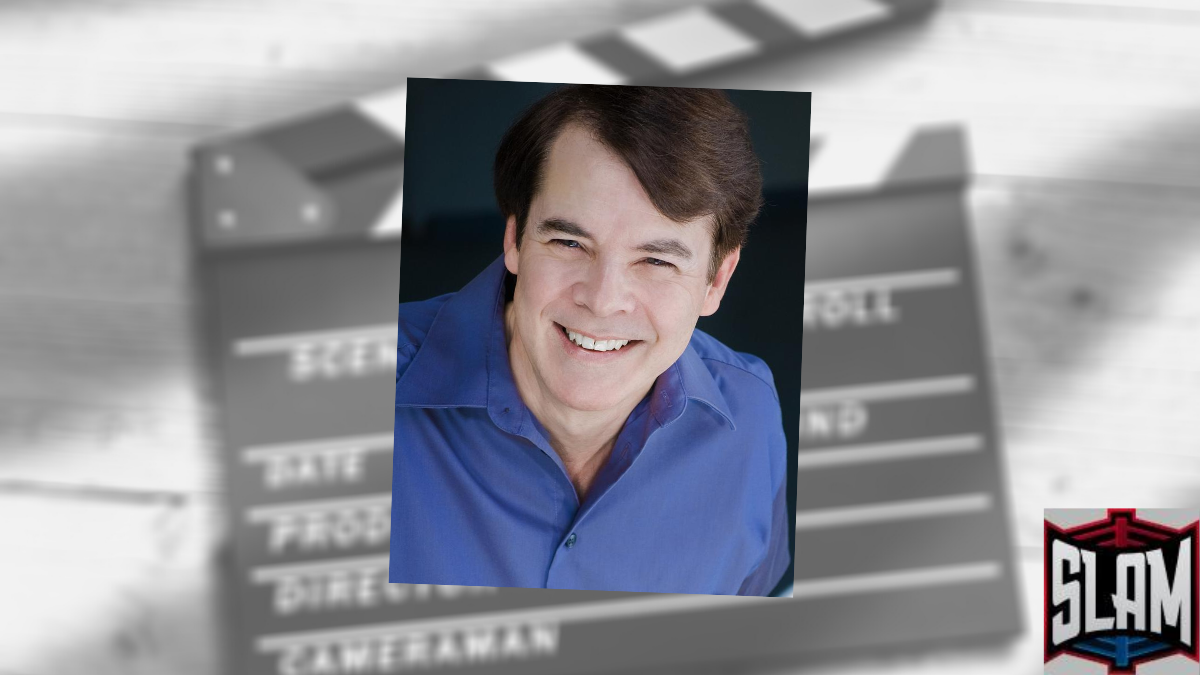

Paul Guay is a screenwriter whose films has grossed over half a billion dollars — from Liar, Liar to Heartbreakers to The Little Rascals. At a recent screenwriters’ conference at which Guay was part of a panel, Slam Wrestling had an opportunity to learn about the lost wrestling scene from Liar, Liar before the conversation turned towards all things wrestling.

In the film, one of the crucial transitional films for Jim Carrey from hyper-reality films like Ace Ventura to more thoughtful comedy and eventually pure drama, Carrey’s character is a lawyer skilled in the art of lying who is forced to tell the truth for 24 hours, as wished for by his son. In the original script, one of the last straws leading to his son making the wish has Carrey taking his son to a wrestling match, only to be so wrapped up in his work that he barely seems to be present.

“The scene was shot at the Olympic Auditorium and they had thousands of extras there,” Guay describes. “Gene LeBell played the ref for that match, and he also was the booker, so he was going through it with Sting and Big Show who was still The Giant at that time.” This wasn’t to be a scene that happened to have some wrestling in the background; this had the match front and center. “The Giant throws Sting out of the ring, right next to Carrey who barely looks up because he’s so preoccupied with his work,” explains Guay. “There’s a shot at his son looking mournfully at his dad, and of course the point is that even when you take me along you don’t have time for me.”

Don’t rent the movie looking for the scene thinking that you must have stepped out for popcorn at the time. It was cut from the film and, given the Hollywood tradition of keeping things on a need to know basis, the writers weren’t told why. Guay can only offer his opinion as to why.

“It works fine,” he begins, dismissing the idea that the scene didn’t mesh thematically or that it wasn’t funny enough. “We wrote it as one paragraph of action, because we just wanted to make the point, but once they had rented the auditorium and had the extras, the scene as filmed took much, much longer than we had envisioned. I guess they figured since we’re here, why not take advantage of the opportunity. My guess is that when they saw the footage they felt it was longer than necessary for the point we wanted to make.”

Instead, we have a scene in Fletcher’s office whereupon he receives a new case and a slew of paperwork to go with it, and his son just knows that wrestling has gone by the wayside. Guay admits that the story works without that scene, but he would have gone in a different route had he known it wasn’t going to be included.

“Since they left in all the times when Carrey’s son is talking about wrestling and going to the match, had we known they were going to cut it we would have come up with something else that paid off on screen.” There is still enough wrestling embedded elsewhere into the film to suggest that wrestling itself was welcomed by the producers (most notably, Fletcher keeps coming after his son with The Claw, which, according to Carrey himself, the comic’s dad used to do to him in real life), but it just so happened that the most in-your-face wrestling scene became expendable.

Still, Guay can’t help but lament the fact that wrestling is usually not welcome within Hollywood as serious subject matter. “It seems to me that most of the people why portray wrestling (in Hollywood films) have no affection for it and no knowledge of it,” he laments. In referencing … All the Marbles as a typical example, Guay doesn’t condemn the quality of the film itself as much as the approach most films take to showing the wrestling world on the screen. “The conceit of the movie is that wrestling is real,” he points out. “I guess in 1981 you could get away with it more, but given that the truth is certainly out there and is at least arguably more interesting, why not make a good wrestling film that goes behind the scenes and doesn’t lie to us or treat us like idiots?”

Deciding to portray the wrestling world as legitimate sport is one part of the problem, as Guay sees it. The other part is that wrestling almost always ends up being treated as comedy … and bad comedy at that. Guay chooses another wrestling film to make an example: “I thought Nacho Libre was an embarrassment,” he says matter-of-factly. “Everything about it was exactly what I don’t want to see. When I see a wrestling scene in a film it’s almost always like a bad Saturday Night Live sketch. I don’t want to just see some steroidal idiot yelling into the mic and cutting a promo — to me that’s not what professional wrestling is. It’s suspension of disbelief through athletic moves and grace and psychology. The people who short-change it are just doing the stereotype, and I have a negative interest in the stereotype.”

It isn’t even just the wrestlers that suffer from a stereotype, according to Guay: it’s the fans. “I remember Ready to Rumble treated the wrestling fans in the movie as idiots,” he says. “I thought: let me get this straight: this is your target audience, so your idea of how to market to them is to treat them like fools? I just didn’t get it.”

From Guay’s perspective, it’s clear why wrestling, and wrestling fans, exist only in stereotype in Hollywood. “I really think it’s as simple as the fact that it’s fake,” he begins. “Because it’s fake people look down on it, which doesn’t make any more sense than saying: who likes Hamlet, that’s fake!” He goes on to point out that the “real versus fake” debate simplifies the complexities of good storytelling in wrestling and gives people an easy way to label the sport-entertainment conglomerate and its fans.

“Yeah, it is fake, but is it well done? Do you get involved with the characters and their personalities? I think people stop at, ‘Oh it’s fake, therefore it’s for children and idiots.’ Well, there are children and idiots who like wrestling, but there are also intelligent people who like wrestling. Why not make a film that appeals to every semi-intelligent person out there? Those of us who fell in love with wrestling fell in love with it for a reason. Why not show the excitement of it, the ability to engage people? The experience of seeing a great wrestling match live hasn’t been portrayed anything like it could be on screen.”

Well, that makes for a good question: why not make a film like that? And who better to ask than a lauded screenwriter who has the connections and clout to pitch something like that film?

“I’ve actually pitched a wrestling film,” he replies. “I’ve pitched a movie that goes behind the scenes of wrestling. The reaction is: who goes to wrestling movies? Who are these people that watch wrestling? I don’t understand — get out of my office!” Guay is quick to make jokes and poke fun at himself, but there’s a palpable frustration behind that last remark.

French author Jules Renard noted that writing is an occupation in which you have to keep proving your talent to those that have none. Guay’s brick-walled attempts to pitch a serious wrestling film may not be a result of a dearth of talent in those he’s pitching to, but Guay does make it clear that he has been frustrated by pitching his passion to deaf ears. “I’m a nerd so I brought my 20-30 hardcover wrestling books to the pitch, because I wanted to establish myself as a bona fide expert,” he continues. “I love this stuff, and there’s a great story here. These are fascinating, larger-than-life people. What is it that drives these people to do what they do? There’s only a few hundred people in the United States who are doing this and it’s one of the last vestiges of the carny lifestyle of the circus. They are conmen who are simultaneously open about the fact that they are conning you.”

After disparaging the films already mentioned, Guay acknowledges that there may be more hope for the upcoming Darren Aronofsky film The Wrestler, possibly because of the pedigree of the filmmaker who has delivered thoughtful films such as The Fountain and Requiem for a Dream. Still, Guay points out that no matter the tone or story in upcoming drama, it still won’t fully realize the potential of the story floating in Guay’s own head. “If you’re dealing with Mickey Rourke, he’s gotta be 50-plus years old,” he points out. “I assume it’s about a retired wrestler who gets back in, so you’re already sort of doing Rocky V or VI instead of Rocky. That doesn’t mean I won’t see it but if I wanted to do the classic wrestling movie I would start with a guy who’s going in at the right age, with the right look, and ‘X’ happens to him.”

It would make for a straightforward wrestling story, one that Guay concedes would demand the loss of “nudge-nudge, wink-wink” trappings that exist today to appease knowledgeable wrestling fans who want in on the secrets. “When I started watching wrestling, it wasn’t ironic,” Guay recalls. “One of the things that Vince McMahon did is to put quotation marks around it. … When I started watching, people were trying for the suspension of disbelief. Bad guys were really trying to make you actually hate them. They weren’t tweeners, they weren’t winking at the camera. You actually believed that if you go to the Cow Palace, Dutch Savage is going to try and break the fat neck of Pat Patterson. Now that’s a promo that I remember from 1973. Thirty-five years later I remember that promo, because Dutch Savage convinced me that he meant it. In contrast, I probably couldn’t tell you what I saw on Raw on Monday night. There’s a reason for that: not only because we imprint more easily when we’re young but also because there was a sense of conviction and lack of irony.”

Admittedly, this sounds like a codger alert. It would be easy to presume that Guay is yet another in the long line of older fans who simply fail to see anything redeeming in the modern world of wrestling. As the discussion continues, though, Guay explains how pitching his film led to a spot at the WWE writing table, and it becomes clear that he has plenty of enthusiasm for many of today’s performers — just not for the majority of stories in which they are asked to perform.

“I pitched my wrestling movie to WWE Films and the then head of the film division said they’re not doing wrestling films” Guay offers, at once understanding of the mandate for WWE Films to establish itself in the non-wrestling arena, but obviously frustrated to have hit another dead end. “But, he said Stephanie McMahon was looking for writers for the TV show because at that point the ratings were not doing well (this took place in the latter part of 2002). She called and we talked briefly on the phone, then I flew out to Connecticut and interviewed with her. I told her what I would do with the WWE booking if I were God, and then she brought me the next day to meet with Vince, Paul Heyman, Brian Gewirtz, Michael Hayes, Triple H, and all the writers around the table. I sat down and Vince said ‘shoot.'” So I pitched them my approach and Vince hired me.”

So, for every fan who’s ever sat back in their living room and groaned about what a better show the WWE would have if only they could write the stories: listen up. “When I was in the writer’s room, you wouldn’t know if you were being worked or not,” Guay explains. “Part of it is political because some people want to see the new guy fail, but part if it is just fascinating because with every word that comes out of someone’s mouth you’re not sure if it’s just to see if you’re smart.”

There existed, therefore, a clear conflict between the management’s desire to bring in storytellers from the mainstream realm, and the old school mentality of the wrestling storytellers and wrestlers themselves. “Vince wanted to hire somebody and Stephanie wanted to hire somebody, but I think there’s always resistance some people at any company to the new guy coming in,” Guay explains. “Is he going to upset the apple cart? Is he trouble? Will he be here two weeks from now? I remember one of the first things I was asked by one of the gentlemen was how many bumps have you taken (done in Guay’s best gravel-laden voice), which I thought was so sweet and endearing and pertinent. I thought of offering to go in the ring and letting him stretch me, because if making me scream like a woman was going to make him feel more like a man, then let’s get it out of the way and we can move on to writing some good television.”

Guay was also on-hand to witness the tumultuous relationship between Vince and Heyman. “They’re both very strong personalities that were, when I was there, pulling in different directions, and it was clear that there were personal issues that were affecting what was going on,” Guay theorizes. During his time, though, and even after his short tenure had come to an end, Guay developed enormous respect for Heyman’s abilities behind-the-scenes. “When I talked to Paul privately, I was more impressed by what he said than by anyone else I’ve ever met in the wrestling industry,” he explains. “His ways to pitch stars, to make stars out of guys … I’ve never encountered anything like it.”

Guay quickly points out that his admiration for Heyman does not necessarily preclude admiration for McMahon, and he doesn’t feel the need to enter into an “either-or” appreciation of the pair. In fact, he suggests, he can understand why, on the surface, some may find it hard to appreciate Heyman for his talents. “You’ve got Vince, whose company is worth a billion dollars,” Guay begins. “You could say ‘What has Paul Heyman done?’ He joins a tiny company and runs it into the ground. That’s true, that’s part of Paul’s story. But the other part is that he kept creating stars who were big enough that WWE and WCW were poaching them from this guy who they don’t even admit exists, although apparently Vince is helping to fund the company under the table. What is it about this guy who hires unknowns but is showcasing them in a way that makes you want to poach them and bring them onto the main stage? This is an interesting guy. I remember when I was there and we were talking about an upcoming pay-per-view, and Paul and I were out in the parking lot. He was pitching me on how to make Tommy Dreamer challenge for the title. Before he said anything I thought ‘Why do I want to see Tommy Dreamer challenge for the title?’ Ten minutes later I was thinking I want to buy that pay-per-view, that’s a story I want to see told. Heyman is just great at creating a scenario that you’d want to invest your money to see, which is a remarkable talent.”

As for his own talents and how he influenced decision-making with the WWE creative team, Guay is matter-of-fact about his visible legacy with the WWE. There is nothing that I contributed that made its way onto television,” he states, though he did have one idea coming in that, as it turned out, the story team was already developing. “When I was there they were just making the decision to have Kurt [Angle] fight Brock [Lesnar] at Wrestlemania and, before I joined, I was going to pitch them Kurt and Brock at Wrestlemania. They actually did it to their enormous credit.”

It was the type of match that had the old-school fan in Guay understandably excited. “It was so exciting because of the legitimacy that those two had. Kurt, I think, is one of the best workers of all time, and Brock was such a massive piece of meat; he had the physique and he had the quickness, and he had titles in the amateur level that made him a completely credible contender. I remember, though, being unhappy when they were going to flip him to babyface because there weren’t enough babyfaces to fight him. Heyman was his mouthpiece at the time, and the combination of what Brock, as a heel, had in the ring and what Heyman brought on the mic was just wonderful.”

Guay also pushed for legitimacy and credibility in the oft-maligned women’s division. “I remember a couple of matches between Victoria and Trish [Stratus] on TV that were really hard-fought and really exciting, and much better than what the guys were doing at the time,” he explains. “When I was in the writer’s room they were looking for a backstory about a beauty pageant or something and I remember wondering, ‘Why would you want a backstory for something so exciting?’ Let’s not make it worse with some wrong-headed story about why they’re angry at each other — how about they’re angry at each other because they want to win a wrestling contest? How about it really matters to them? Let’s save the backstories for others who need it — these were legitimately exciting matches.”

It is this same belief in legitimacy and credibility that Guay feels elevates wrestling to its purest artistic level, and he tried to push that agenda while in the writer’s room. “My point of view was that titles matter, wins and losses matter,” he says. “You don’t have to sell twenty-one storylines in the course of two hours. You’re trying to sell a pay-per-view. You’re going to make me want to buy it with a credible main event and maybe one key supporting match.” What weighs a card down, in Guay’s view, is that it is stacked with matches, all embedded with their own detailed storylines, to the point that it de-emphasizes the main event. As to how that style of booking has come to be, Guay offers this estimation: “My guess is that on the writing staff everyone wants to keep busy and everyone wants to contribute, and that makes total sense. But if you have a title match, the importance of the title is such that you don’t also need a personal story line. These should be the best wrestlers in the world competing. The audience should be thinking ‘That wrestler is holding the belt for a reason. If he’s a heel he may have cheated his way into it but he’s incredibly smart and sneaky, or if it’s a babyface it’s because no matter what the heel does he can find his way to win. The title should matter and it should actually matter who holds it.”

Ultimately, Guay is a fan. He’ll continue to follow WWE and there is always the chance to work with the world’s biggest wrestling company down the road. And if his wrestling movie ever comes to the theatres, don’t worry, he doesn’t plan on treating you like an idiot.