Bill Anderson never wrestled a championship match in New York’s Madison Square Garden. Nor did he aspire to become champion of the world. His goals were relatively simple: to work his way up the ranks of the local promotion, to build a career, and to wrestle in Japan. If one were to tell Bill Anderson starting out that he would end up impacting the world of professional wrestling decades after he retired as a wrestler, he would have said you were nuts.

But he did all that, and more. It’s a story as unique as he is.

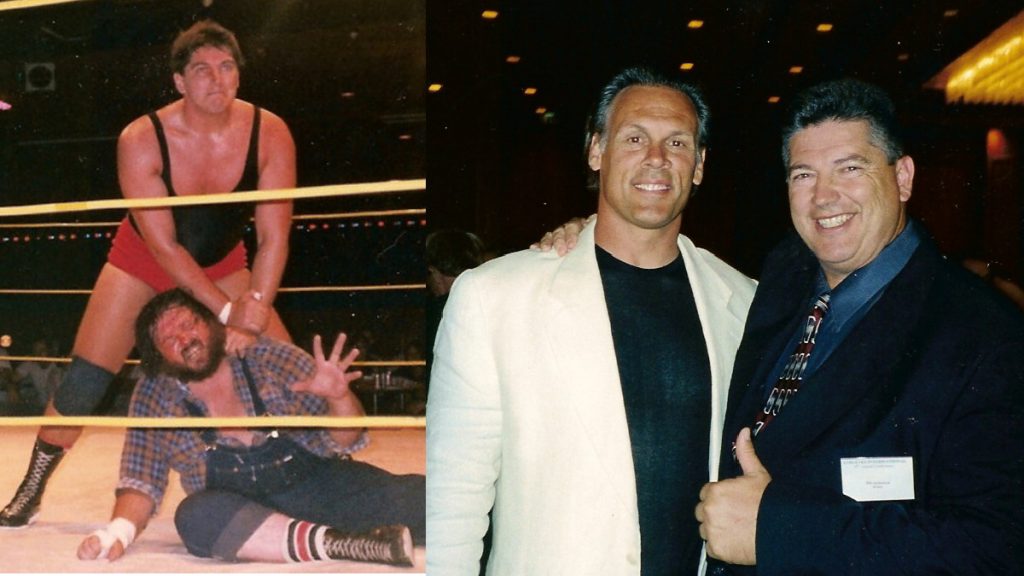

Bill Anderson and Roddy Piper

Anderson’s ability to adapt with the times and to develop genuine relationships with people were instrumental factors throughout his career. Anderson not only would become one of the biggest babyfaces on the SoCal circuit, he would pass on his knowledge of the business as a trainer, molding and preparing future legends such as Sting, The Ultimate Warrior and the late Louie Spicoli, among many others. Even the bright lights of Hollywood would beckon Anderson, as he appeared on the big screen in over 12 movies, including director Tim Burton’s Ed Wood.

“He was good at making friends in the business. Networking wasn’t my high point,” said his longtime tag team partner Tim Patterson. “That was one thing he helped me out a lot on when we were working together and stuff because everybody got along with him. It was cool being on the road with somebody you could get along with.”

Anderson was born November 12, 1956 in Detroit as Bill Laster. His parents divorced when he was six years old and was raised by his mother in California for a time before settling in Goodyear, Arizona, about 15 miles from Phoenix.

He recalled the moment that sparked his interest into wrestling. “The big event in my life was one day in ’71 when watching TV one day in California and John Tolos threw that white Monsel’s powder into Freddie Blassie’s eyes. I was watching it live on TV,” he reminisced to SLAM! Wrestling. “Kurt (Von Steiger) thought Blassie was going to Japan, but I didn’t know that. I thought the poor guy was blinded like all the other fans did. It hooked me right there on that TV show and I told Tolos this story many times; we’re still friends to this day.

“That was the event in my life as a 14, 15-year-old that just totally hooked me. There was something about this business, this sport, that I really want to do this and I know that it sounds like a fan thing to say, but that’s really where I came from and my mentality and I just wanted to do that,” he said.

Anderson became serious about becoming a wrestler. He began checking out the main arena in Phoenix called the Madison Square Garden (named after the famous arena in New York). Built in 1929, it was where all the stars wrestled when they came to Phoenix before being torn down a couple of years ago.

“It was here as a fixture in Phoenix for many years and that’s where I trained for wrestling in ’73. But in ’71 I saw guys like Cowboy Bob Ellis, Ben Justice, Arman Hussian, and Don Arnold used to wrestle as ‘Dr. Death.’ Chris Colt, Ron Dupree, there were a lot of guys who came through here,” said Anderson.

That Ernie Mohammed promotion would eventually shut down but a new one came in and with that Anderson would get his break in 1973.

“I was a junior in high school, and this guy named Kurt Von Steiger (Arnold Pastrick) started running shows,” said Anderson. “He came from Amarillo but he was living in Portland at the time so he was back and forth in those territories. He started promoting and I got to know him, and I started setting up the ring for him and ended up becoming a referee and ring announcer for him in ’73. And my deal with him was he would train me for free as long as I worked for him for free, which I gladly did. I set up the ring, I worked concession, I did whatever he needed, I was just thrilled to death to be around the guys.

“And he was using guys like the Afa and Sika — The Samoans — here. Bobby Jaggers got his start here in Phoenix when he worked as Bobby Mane at that time, a rip-off of Lonnie Mayne. There was just a bunch of guys who came here from the Amarillo territory, Karl Von Steiger, Apache Gringo, different guys like that.”

Bill Anderson wrestles Adrian Street.

“I first met him in Detroit, Michigan at a WFIA Convention (Wrestling Fans International Association) in the early ’70s,” recalled professional wrestling historian Tom Burke. “He was going into his first year as a high school freshman at the time, visiting his dad who lived in Michigan. He lived with his mom in Arizona and his step dad and brother Bobby.”

Burke elaborated on how he became acquainted with Anderson. “What sparked our friendship was my needing a correspondent in Arizona,” he said. “Little did I know that our initial contact would last to this day. It was while he was in Detroit that two friends of mine were wrestling in Arizona at the time – Chris Colt and Ronnie Dupree. They were working for promoter Ernie Mohammed at the time. Bill knew both of the wrestlers and was in awe of Chris Colt’s working style.

“Chris Colt was on top, running a feud with Ronnie Dupree,” continued Burke. “Billy, at this point, was a junior in high school. Bobby Jaggers, Chuck Karbo, a real vet and great guy, Tito Montez, Marylin Bender, Princess Tomah and others were some of the main guys in the Arizona territory.

“He finished up high school with Jesse Barr in his graduation class.”

Von Steiger left for Portland after about six months with Anderson tagging along for the ride. The plan was for Anderson to work as Wilhelm Von Steiger — Kurt’s German son — in 1974 but real-life problems between Von Steiger and his wife Teri turned the 17-year-old Anderson into a third wheel and he returned to Phoenix in May of 1974, arriving to yet another new local promotion to which he joined.

It was Harvey Kramer, the new Phoenix promoter who gave Anderson his first moniker “Flying Billy Anderson” as it personified his all-American babyface look.

“I was 6-2, 175 pounds soaking wet,” Anderson recalled. “Boy, I wish I was 175 again.”

His first match was against Buddy Rose (not Paul Perschman) in Tucson on June 16, 1974. After a year of breaking in and working three to five shows a week, another opportunity presented itself.

“In August of ’75, Chris Colt was working this territory and he said ‘I want to go back down to Tennessee and work for Nick Gulas and Jerry Jarrett, do you want go with me? You could be my brother; you can be Bill Colt. I’ll bleach your hair blonde and that sort of thing.’ And I thought, ‘Well, why not, it sounds like an adventure.’ And it sure was, for a kid that was, you know, 18 years old, it was a big adventure,” Anderson said.

“So I went down there and I got to work with Jackie [Fargo], Don ‘Roughhouse’ Fargo, and Bobo Brazil. We worked everywhere from Indiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, Kentucky to Alabama.

“There were about eight or nine states we could go into. We were wrestling seven days a week, three times on Saturdays. Monday night we’d be in Memphis, at the Mid-South Coliseum, Tuesday might be the Louisville Gardens in Louisville, Kentucky, Wednesday might be Nashville at the Fairgrounds, Thursday we might be heading to east Tennessee to some of these real redneck towns, and Friday probably down to Alabama, and Saturday in Alabama for Birmingham and TV in the morning, and then like Huntsville, Alabama TV in the afternoon — and then go to Chattanooga, Tennessee for a house show that evening.

“There was a lot of driving. They used to call it the ‘Ol’ Gasoline Circuit’ back in the ’70s and it really was. We would just drive our butts off. It was usually 500-mile trips a day. You just did it.”

Anderson’s days in Nashville were some of the most enjoyable — and lucrative — of his wrestling career, but the mental and physical demands were taking a toll.

“Of course, that was my introduction to speed and things like that, because as a kid I didn’t know any other way other than I was told ‘Take this, it’ll help you drive.’ You just do it, and I was never much on alcohol or anything, but I started taking that kind of stuff just to get through the days, because we had hundred and hundreds of miles between shows.

“In Tennessee, I was making about $500-$750 a week. As a kid that was big, big money back in ’75,” Anderson continued. “I didn’t know what do with it, making that kind of money. In those days you’d get paid well for Memphis because it would usually be a sellout. So maybe $175 for Memphis, Nashville might be a $50 or $75 payoff. Some of the other towns, might be $25, unless you’d get to Chattanooga might be a $100 payoff. It all came out to a pretty decent week. That was me; some of the other guys of course were making a lot more than that. Tommy Rich, he was just starting out there, he was making a lot more than me. He was driving a brand new Cadillac, so I think he was.

“I spent probably four months down there, and I just couldn’t handle it. I was burned out at 18, I mean all that traveling. And Chris Colt was just a wildman, drinking and drugs and everything and he just couldn’t get along with anybody.”

Booked to wrestle for promoter Dean Silverstone in Seattle, Anderson — on the spur of the moment — decided to take a sabbatical while changing planes at O’Hare airport for a year and stayed in Chicago with his sister for six years.

After a year of the regular life, the intrigue of wrestling slowly came back.

Working a full-time job, he wrestled part-time for Dick the Bruiser’s promotion in Chicago but grew tired of the brutal winters, so he moved back to Phoenix in 1981.

Anderson sent his 8×10 picture to Mike LeBell’s promotion in Los Angeles and was hired by the booker Tom Renesto on August 26, 1982. He worked with Chris Adams, Adrian Street, Tim Flowers and Hector Guerrero but stumbled upon a discovery that would fundamentally change the wrestling business as he knew it.

“We used to go down to a Hispanic station and do our promos for the TV and all of a sudden, we got down there, we weren’t taping TV anymore, Mike was showing tapes from guys back east,” he recalled. “S.D. Jones, you know, and Adrian Adonis and different guys like that and it was like ‘Wow. This is really strange.’ And Mike says, ‘Yeah, this is the way it’s going to be. I’m selling out to Vince and I’m in a non-compete clause for ten years. Vince is going to come in here in March of 1983 and start running at the L.A. Sports Arena. I’m going to be in charge in booking some talent. I can’t use everybody on these shows but I’m going to use some key people.’

Bill Anderson and Vince McMahon Jr.

“Luckily, Mike booked me every single time on every show for several years that he was in charge of. That was my big break because I got to become friends with Jay Strongbow, one of the road agents, Pat Patterson, Tony Garea, Jack Lanza. All of the agents, Rene Goulet, they all became friends and that really helped me a lot.”

Anderson usually worked the opening matches. In those days, the WWF was still an unknown entity outside its north-eastern territory. “That’s why Mike had to show those tapes, to get the people familiar with Tony Garea wrestling and a lot of these names from the east coast. There were many nights where I’d go out and get introduced and get as big a pop as a Don Muraco would. It was amazing,” said Anderson.

This would lead to the next phase of Anderson’s career with the WWF.

“In ’85, Red Bastien was opening up a wrestling school in Los Angeles, and he needed somebody to get in the ring and train the guys, because he really couldn’t do it. He had artificial hips and as tough as an old bastard Red is, he just still, he couldn’t do a lot of that physical labor at his age and with his health at that time. I was actually living with Red; we had an apartment together. Red says, ‘Bill, I’ll let you move in with me on one condition — I’m going to be opening up a school and I’ll let you stay rent free; but I need some help in the ring.’

“I said ‘Yeah, I don’t care.’ I was young, like 28 – 29 years old at that time. I said, ‘Yeah Red, whatever you need brother, I don’t care.’

California Training: Left to right, Mark Miller, Dave Sheldon, Bill Anderson (kneeling), Steve Borden, Steve DiSalvo, Jim Hellwig, Red Bastien (kneeling), and Garland Donoho.

“And that’s where that class with Sting – Steve Borden, The Ultimate Warrior, The Angel of Death, and Steve DiSalvo. Strangler Steve DiSalvo and two other guys that didn’t really go anywhere, a guy named Garland Donoho, and another guy Mark Miller. Those two never really achieved much greatness after that.”

The training was an intense crash course six to eight weeks in length and six hours a day a night, six days a week.

“So the six of those guys, I was in the ring with them a lot. Red did bring in some other guest trainers on an odd night here or there. If I told Red, ‘Hey, I have a booking somewhere, I have to wrestle or something.’ Red would let me take my booking and do it. And he’d bring in John Tolos, or Armando Guerrero or Professor Toru Tanaka; he’d bring them in and be a guest trainer for the night, to let the guys learn different techniques and stuff. So it was kind of cool for them.”

Four of the students — Miller, Donoho, Borden and Hellwig — had their training sponsored at $2,500 each by Rick Bassman, who was looking to book them afterwards as Powerteam USA. DiSalvo and Dave Sheldon, aka The Angel of Death, were not sponsored.

“In those days, it was really unheard of to bring four guys in with matching outfits into a territory. It was really unheard of,” said Anderson.

“What ended up happening after the end of training was done, Red wanted to book all the guys up in Canada to get them experience, for Stu Hart up in Calgary. But Sting and Warrior, they came to me and they asked me my advice. They said, ‘Look, Bill we don’t want to go up to Canada if we can avoid it — it’s cold up there.’ They liked the southwest type of temperatures. They said, ‘Do you have any other ideas?’ And I said, ‘Well, there’s other promotions in the U.S.’

“They told me that they had sent pictures out to Jerry Jarrett and Jerry Lawler at the time. They said, ‘Would you recommend us to go there?’ I said, ‘Hey, it’s a great territory. I worked there a few months. You might burn out, but it’s a great experience. You guys need experience. You need to wrestle everyday and get experience or you’re never going to get better. You can only learn so much training in the ring and without a crowd there. You need to learn that on the road, you need to learn just being on the road, and all the good and bad that goes with it.'”

Borden and Hellwig took Anderson’s advice and headed out for Nashville, while DiSalvo and Sheldon ventured north to Calgary for Hart.

They would eventually find success as Sting and the Ultimate Warrior, respectively.

DiSalvo, who now works as a technical IT workforce recruiter in Minneapolis, fondly recalled his days of training with Anderson and Bastien. “I love both of these guys. Red and Bill were the best. I have spoken to, met and worked with thousands of people since my days with Red and Bill. All these years, I still have not come across two people that cared more and helped strangers advance their careers than the both of them.

“I never did learn how to take a bump, or learn how to wrestle, which is no reflection on both of their abilities, they tried to teach me. What I did learn from them were the finer, more subtle approaches of wrestling. Work the crowd, play to your strengths and most of all communicate facially, bodily and vocally. Always respect and take care of your opponent, and always remember you are there to entertain and have fun. I still use those ideas and concepts in my business today. Voice reflection, facial changes, etc.

“I can only thank Red and Bill for teaching me the skills I needed to excel outside of wrestling and be a success.”

Asked to compare Bastien and Anderson’s styles, DiSalvo complimented both of their all-around approaches. “Red with two bad hips was still able to bump better than me. Bill could do everything.”

Anderson continued to wrestle and referee for the WWF in California until 1988, when ring announcer Lee Marshall bolted the company over a dispute, leaving a ring announcing vacancy. Strongbow asked Anderson to replace Marshall at the Los Angeles Sports Arena that night.

Bill Anderson, WWF ring announcer, poses with The Blue Blazer (Owen Hart).

He recalled being a nervous wreck before his first announcing gig. Things went well however, and he went on to do much of the ring announcing across southern California, much like his colleague Michael Porter did in Northern California.

“I had the job for many years after that,” Anderson said. “They flew me all across the west coast; they even flew me to Vegas, Denver and some different arenas. They even flew me to Hawaii, six to eight times to the Blaisdell Arena in Honolulu. Because I’d had wrestled there in the late ’80s for Leah Maivia and so I was familiar with that building. I’d fly in at five in the evening, get to the arena for like a 7 o’clock start of a show and then have a 10:30 flight out, so it really wasn’t spending much time on the islands,” he laughed.

“My wife used to go crazy. She would be like, ‘Why can’t I go? I want a vacation like you,’ and I would say, ‘Vacation, are you kidding me? I’m on the island literally for like six hours to do a three-hour show. It’s not a vacation!’ She never understood. Never.”

Anderson started up his own wrestling school around this time called the Bill Anderson School of Wrestling. One of his first prized students — a young 17-year-old up-and-comer who sought him out after a show after talking to Jack Armstrong about becoming a wrestler — would later become his best friend and have a major impact on his life.

His name was Louis Mucciolo, who became Louie Spicoli. February 15, 2008 marked the 10th anniversary of his passing.

“Louis was one of the most natural guys I ever trained. It’s just a shame he let the business catch up with him too much and he got caught up with the wrong people. He was hanging around with Scott Hall and Kevin Nash, and Sean Waltman and all those other clowns in WCW and got caught up with too much drugs and stuff,” Anderson said somberly.

Anderson’s school was turning out good wrestlers like Ricky Ataki, and finding work primarily in the WWF, UWF and Mexico. His friendship with federation bigwigs Patterson and Terry Garvin came in handy, as arrangements were made for Anderson to supply his wrestlers to do the jobs for the WWF Superstars and Wrestling Challenge tapings.

Louie Spicoli and Bill Anderson signing autographs in Tijuana, Mexico.

In fact Spicoli wrestled his two matches in the WWF in Minnesota, wrestling “Outlaw” Ron Bass in Duluth, and Greg Valentine the very next night in Rochester. Knowing Strongbow would never allow a rookie to wrestle, Anderson put his reputation on the line, putting Spicoli over as an experienced wrestler to the Chief.

“Ron Bass even came back after and said, ‘Hey that kid is good man! You need to keep bringing him.’ Strongbow then said to me, ‘Billy, good job! I like this kid. Start bringing this kid around. When we do California tapings like next month, bring that kid,'” Anderson said.

He confessed to a shocked Strongbow ten years afterwards.

Anderson had a knack for turning out wrestlers, but what made his school so special that CNN and Time Magazine did feature stories?

“I credit a lot of my training to Bill and Louis collectively,” said the now retired Jason “Primetime Peterson” Peters, who trained for a year and half with Anderson beginning in 1991 at the Slammers Wrestling Gym which at the time was owned by Verne Langdon in Sun Valley, California.

“They did everything, as far as just getting connections. One thing right off the bat was we’d go to training and then you know there would be The Undertaker sitting there. We’d go in there and one night here’s Missy Hyatt and Jason Harvey or Susan Sexton. It was just crazy and it was right away and Louis was already working the tapings so right away he kind of took us under his wing and we became friends. So I credit the both of them, and Louis, he just had that charisma factor right from the get go. But Bill had the connections, and that was one of the initial things, just the big time connections right away. They’d take us to the WWF shows and get us backstage, but just the basic stuff and they always took care of us.

“We’d always go out to train and then afterwards we’d all go out to eat at Denny’s. That was always the thing that happened. Within two or three months I had my first pro match, so they really looked out for us, the both of them.”

Patterson, who would occasionally stop by to say hello and help out, noted Anderson’s gift of the vernacular. “I would do the move and say, ‘Try to do it as I do it,’ while he was able to put into words what they were doing wrong and put into words how to fix things,” he explained. “I think what helped a lot with him being a trainer was he was good at communicating the things for them to do to make it where they could follow step by step on how to do those moves properly or how to correct something they were doing wrong. It was the communication.”

Perhaps the final ingredient was the fun.

“Bill was just a comedian, that was one thing,” laughed Peters. “If you were going to be around Bill he was always going to be joking around. I can just hear his laugh now. You were always going to have a good time.”

With his school established, 1991 marked the first opportunity for Anderson to wrestle in Japan for Frontier Martial Arts Wrestling (FMW). It offered a wide variety of wrestling matches to its fans, from boxer-wrestler matches to midgets. He wanted to take Spicoli with him, but he was having “girlfriend problems” so he took Lou Fabiano, a worker who was from the east coast. They were called The Mercenaries, modeled after Anderson’s trio Los Mercenarios team in Mexico.

“We were gone for a month and got to wrestle The Sheik — Eddie Farhat the Original Sheik, Sabu, his nephew, Tiger Jeet Singh and his son Tiger Ali Singh.

“I was thrilled, because growing up in Detroit and as a teenager, I had gone back to visit my Dad. I had seen the Sheik and Tiger Jeet Singh and people like that wrestle. I was a fan of theirs and now I’m in the ring with them. It doesn’t get much better than that,” marvelled Anderson.

“I was like, ‘Wow, I can’t believe it, I just can’t believe it, I mean, this is so cool.’

“I had wrestled the Sheik twice; even one time he was my partner on a show. I ended up doing in ’91, ’92 and ’93. I did five tours of Japan; they were three to four weeks each. That was a real highlight, getting to do that.

“It had been instilled in me in the ’70s, when I was first breaking in, that there was no higher thing in the business you could do than to go to Japan.”

WWA Champs Bill Anderson Louie Spicoli and Tim Patterson as Los Mercenarios (The Mercenaries) in Mexico.

Anderson also ended going to Mexico early and often, including a two-and-a-half year title run in as World Wrestling Association (WWA) Trios Tag Team champions Los Mercenarios in 1989 and a separate stint as WWA Heavyweight Champion in 1986.

Los Mercenarios was a stable, usually consisting of Anderson, Spicoli and Patterson. They defeated Chavo, Mando and the late Eddie Guerrero on July 4, 1989, to become one of the most hated teams in the country. Their legendary rivalries with the Mexican teams of Los Villanos, Los Brazos, Mil Mascaras, Dos Caras, and El Sicodelico, and the trio of Rey Mysterio Sr., Kiss & Karizma sold out arenas all across Mexico and Southern California.

Anderson graced the cover of Lucha Libre — one of Mexico’s most prestigious wrestling magazines — three times; once as himself and twice as Los Mercenarios.

He had accomplished his modest goals in the beginning, set into motion by the vicious act of the Monsel’s powder perpetrated 22 years earlier.

However, it would also mark the beginning of several periods of adversity, some of which would take Anderson to his limit.

Ironically, it would start with the most blissful of events in 1987.

** CONTINUED IN PART TWO: Bill Anderson Part 2: Taking the road less traveled

“BIG” BILL ANDERSON STORIES

- July 17, 2013: Bill Anderson remembers fallen friends in new book

- July 17, 2013: Read Superstar Billy Graham’s Foreword to Big Bill Anderson Remembers … His Fallen Friends of Wrestling

- May 29, 2011: Big Bill Anderson’s book big on pictures

- Mar. 2008 Part 2: Bill Anderson Part 2: Taking the road less traveled