Over the years, Rick Martel‘s brother Michel Martel has become little more than a footnote in the annals of professional wrestling, a forgotten name in a long list of people who made a living at the grappling game. He is only remembered in story and rumor, as recollections of wrestlers who died in the ring are spilled out.

It is sad that someone with a rich, 10-year career full of good times, friendships, championship titles and trips around the world is only recalled for the way his story ends-dying in the arms of a friend on the road after a match in Puerto Rico.

As the saying goes, out of tragedy can come triumph, and Michel Martel’s legacy lived on through Rick Martel and Frenchy Martin.

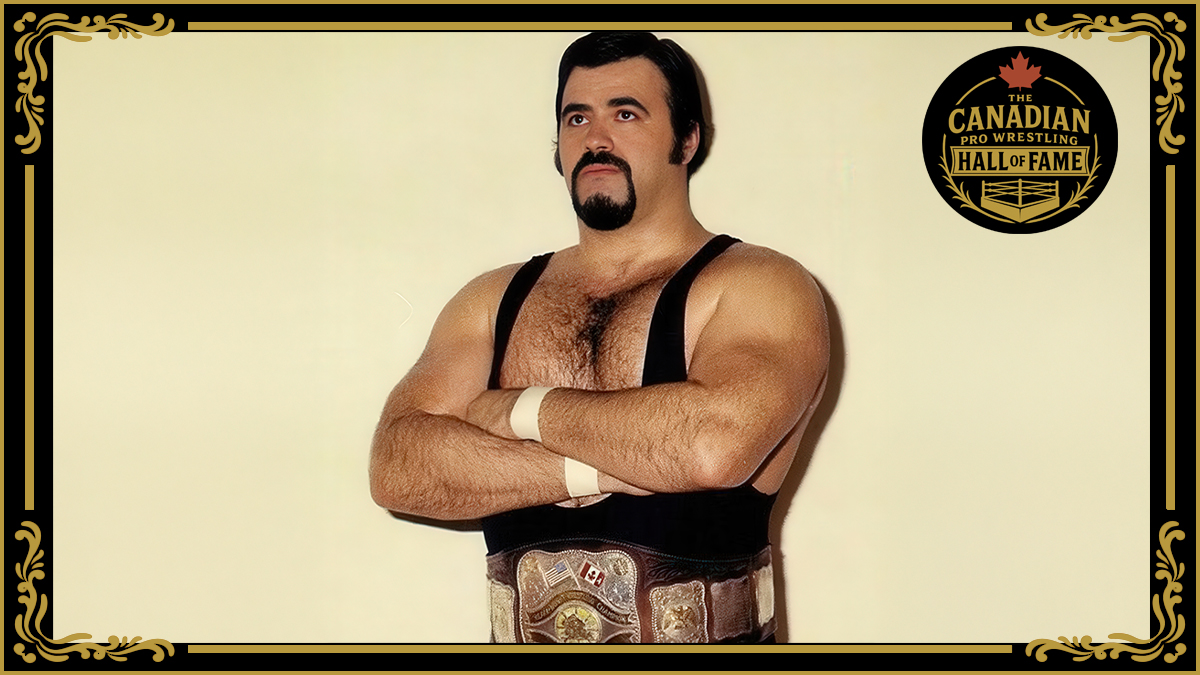

Rick Martel would rise through the ranks to become AWA World champion, among dozens of other top titles he held throughout his Hall of Fame career. Michel Martel’s long-time tag team partner and best friend Frenchy Martin-often working as his ‘brother’ Pierre Martel-had a solid career following Michel’s death as well, with long-running blood feuds in Puerto Rico that used Michel’s death as a part of the storylines.

When talking about Michel, 12 years his senior, Rick Martel’s tone can venture from plaintive and painful to loving and awestruck.

“Michel was my idol, my teacher, my mentor. He was everything to me. He started me. In fact, he made a point of making me get in touch with the wrestling world. I remember when I was 12 years old, he would bring me with him to the wrestling, bring me into the dressing rooms, make sure I meet the guys,” Rick Martel told SLAM! Wrestling. “He’d say, ‘You know one day, you’re going to be in professional wrestling … we’re going to team up.’ He really gave me that fever, that passion. He was a very passionate guy, Michel. That’s the one word that you can use to describe him the best.”

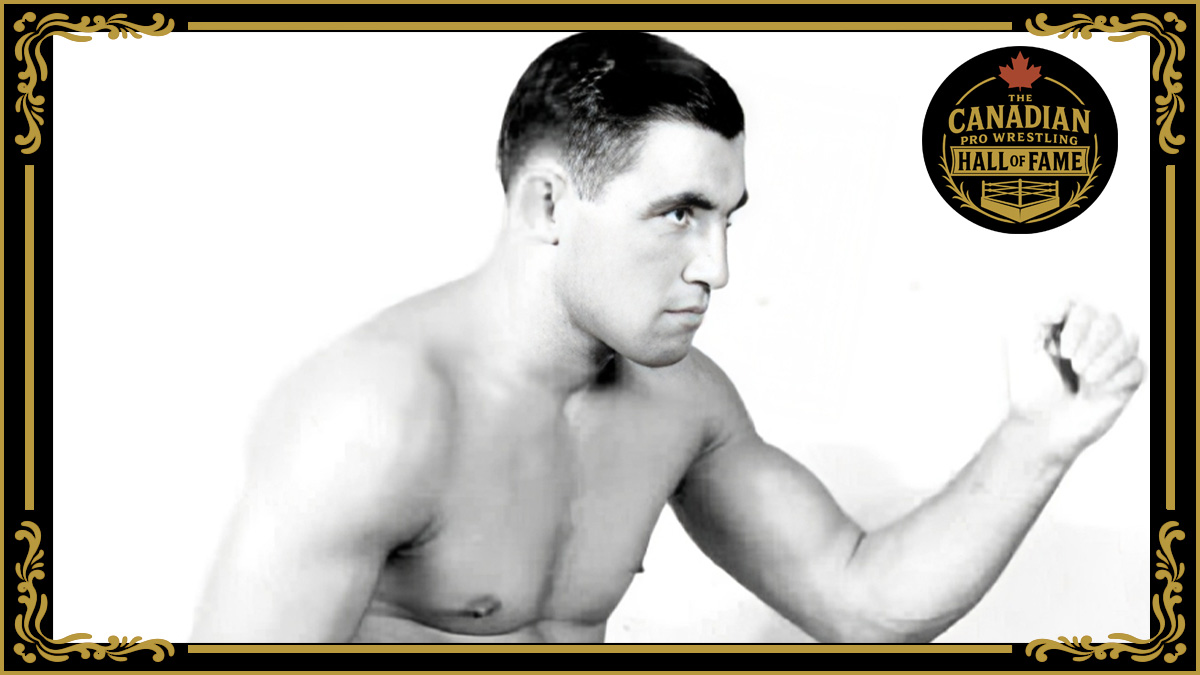

Michel Vigneault was born in October 1944, in Quebec City, the first of six Vigneault children, two boys and four girls, born to Fernand Vigneault and Evelyne Harvey. The patriarch, Fernand, died in 1956, when Michel was 12. Evelyne was to remarry Daniel Lachance.

Michel fell in love with power lifting while in high school, and with his thick shoulders on his 5’10” frame, took to competing a little. At night, he was a good time guy, working around the club scene as a bouncer, bartender and later even as an owner.

“He was the type of guy you liked to have along. He had a lot of jokes. He liked to have a good time. He was always a good-living guy, a happy go-lucky guy,” said Rick Martel.

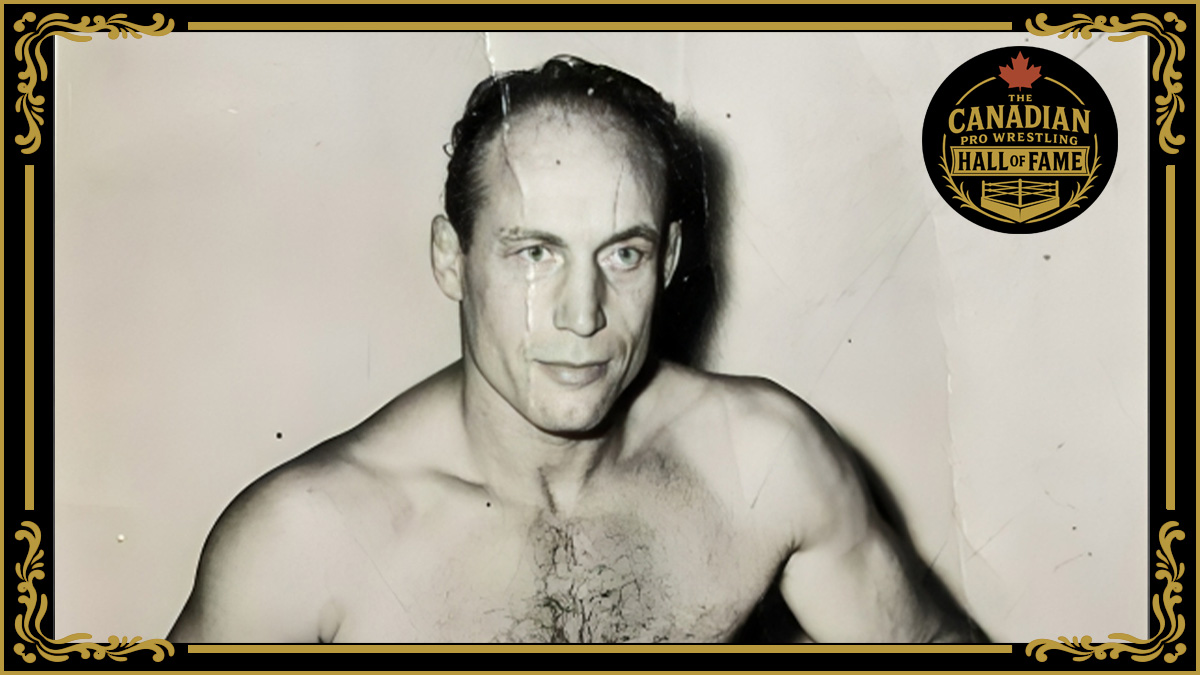

Frenchy Martin (aka Don Gagne) met Michel around the clubs of Quebec, a fun place to work for two fit, healthy, young men. Michel would be instrumental in Martin getting into pro wrestling, and together, they would form a tag team known as The Mercenaries. Frenchy would be there at Michel’s end too.

“The day we met, we both had, I don’t want to say an edge to be pretentious, we were club guys. We were with the program. We could see the program happening anytime,” said Martin. “In the sense of getting together and wrestling, we would look at each other and know what was coming. Michel knew exactly where we were going, I knew where we were going.”

The Vigneaults had two uncles who dabbled in pro wrestling, Real Choinard, aka Bob Casino, who was married to Evelyne’s sister and worked fairly often, and Aldrick Harvey, who was Evelyne’s brother, and was primarily a bodybuilder. Neither uncle ever did much more than local stuff around Quebec. “They worked a little bit for Johnny Rougeau, years ago, just a few matches. They were in touch with that world for a while,” said Martel.

The uncles presented the option of a career in pro wrestling to their nephew. “Michel liked the idea, because he liked power lifting. My uncle said, ‘You should try wrestling. Why don’t you try it?’ He tried it one summer and fell in love with it, so he decided to go into it full time,” said Martel. He was sent up to Larry Kasaboski for a summer tour of Northern Ontario to learn his new craft in 1968. His primary trainer was a wrestler named Vic Tanney, and his first gimmick was with a shaved head as a Mongol. After the tour ended, Michel worked a bit for Johnny Rougeau around Quebec, then got his big break, heading to Stampede Wrestling for Stu Hart.

In Calgary, Michel Martel’s career accelerated, exposed to some of the top names around. And he was smart enough to listen and seek out advice while working as both a face and a heel during his time there.

“He once paid me the highest compliment I got in the business. He came to me, and he said to me, ‘I’d love for you to be my mentor.’ I said ‘Why?’ He said ‘the way you think, your ideas and all that,'” recalled ‘Cowboy’ Dan Kroffat, who feuded with Michel in Stampede.

According to Rick Martel, his brother treasured his time battling Dan Kroffat. “That was a period of his life that he really enjoyed,” he said. “With Dan, he did all kinds of matches, boxing matches, and kinds of gimmick matches with him. They really had good chemistry together. I remember watching them, and those guys could just look at each other and know what to do. Sometimes it happens, you have a guy and everything just flows.”

Also on the Stampede roster was Leo Burke, who would later go on to book Stampede, Puerto Rico, New Zealand and the Maritimes. “I can’t say one bad word about him. He was a professional in the ring and outside the ring. He was the type of guy that always gave 100%, gave the fans what they came to see, whether there was 20 people or 20,000, he never changed. That pretty well puts it in a nutshell. I think he was a great worker as well,” Burke said. “Ricky was more flashy. Michel was great to work on the mat. He was very solid. You couldn’t see through his work, which was the case for more than 90% of the guys!”

Earl Black teamed with Tiger ‘Tweet Tweet’ Tomasso for the Stampede tag titles in 1971, losing them to Michel Martel and Danny Babich. “Michel was a lovely lad, always smiling and great company,” said Black, adding that he used to ride Babich mercilessly, as his English was terrible.

“He was very young and an excellent wrestler. He drew a lot of people,” said Tor Kamata. “He was fun. He liked to party. He liked to get out there. We had a good time.”

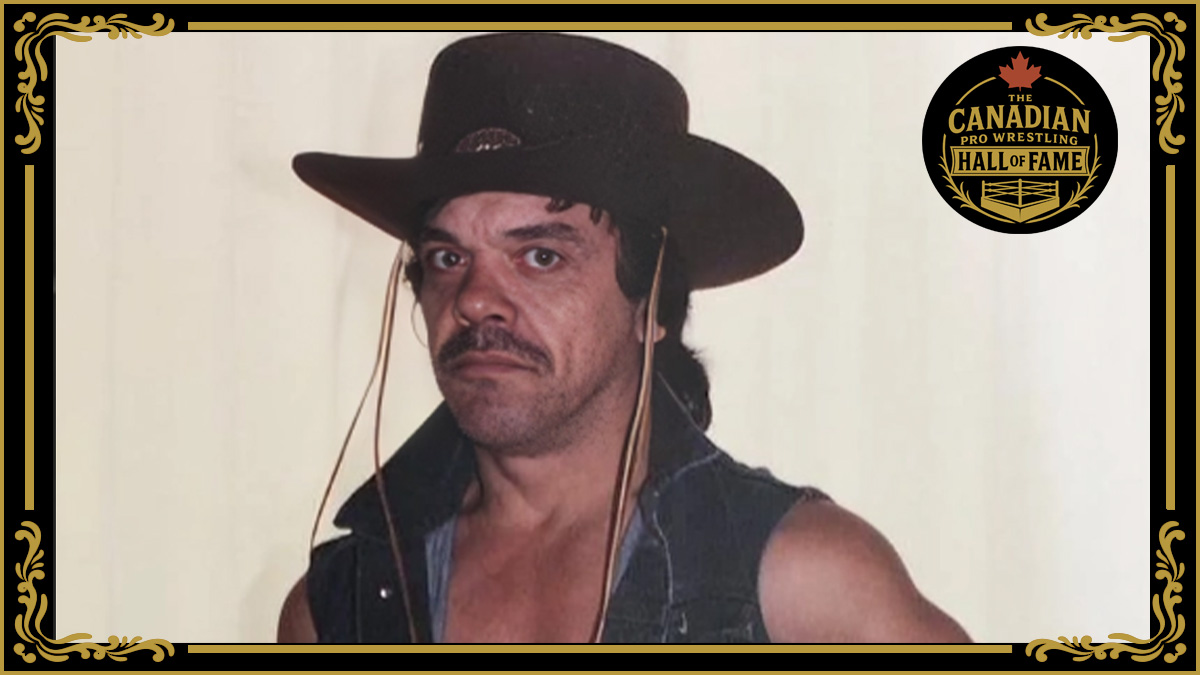

Besides Calgary, and the occasional work around Quebec when he was home, Michel Martel’s other early notable venture was to Mexico, where he wrestled as The Lumberjack. “He had the whole thing, the axe, the toque,” said Martel.

Once established, Michel encouraged his friend from the hometown bar scene to get into the business too. “He just told me he was going to be a wrestler. I went one time to see a match, because I didn’t know about wrestling. I saw Jos Leduc against Maurice Vachon in a cage. I said, ‘Fuck, I’m going to do that!'” said Frenchy Martin. He trained with a few oldtimers around Quebec, then arrived in Calgary as Don Gagne thanks to Michel’s hook-up with Stu Hart. “He booked me into Calgary. I wasn’t really ready, but I still went.”

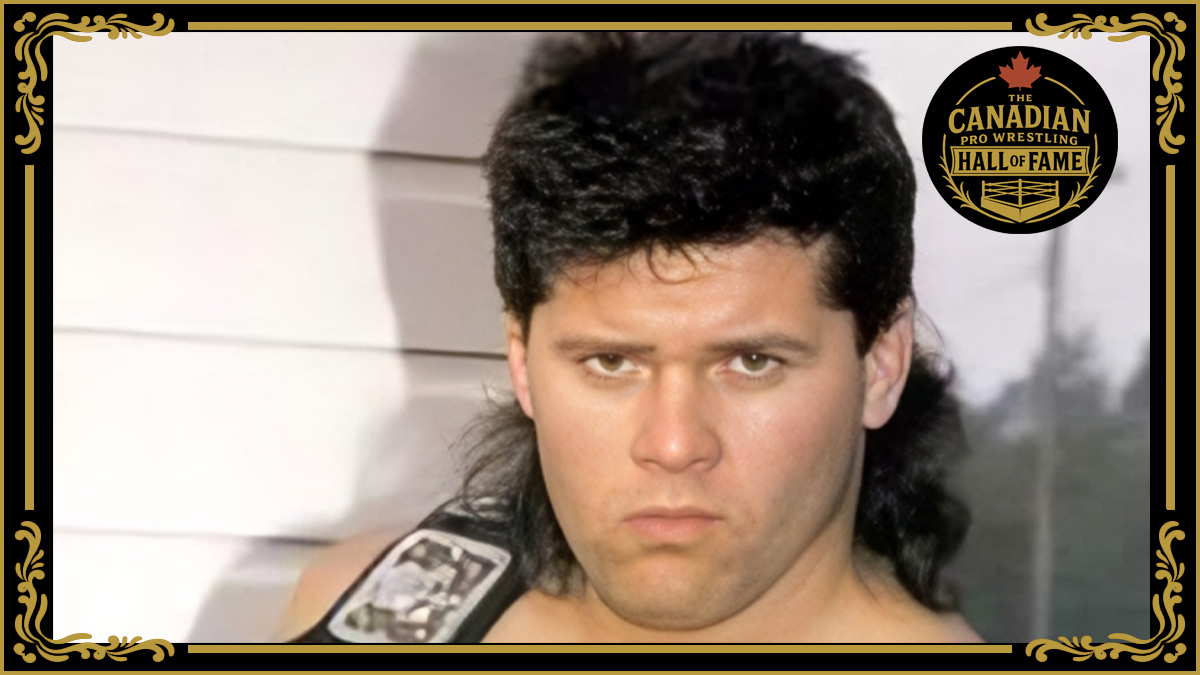

Besides Frenchy Martin, Michel also brought his brother Rick into the sport. Rick idolized his brother, and followed his advice as best he could, even at 12 years of age. “All of my friends were playing hockey and Michel had me doing boxing to learn my way around a ring, it didn’t have to be a wrestling ring. In boxing, at least you learn the balance, the control of your movements in a ring,” he said. “He had this whole plan made for me. If I became any good at all in this wrestling business, it’s strictly because of Michel.”

Rick’s break would come in 1973. “Michel was in the Maritimes and a wrestler got injured and they needed a wrestler within 24 hours. And they couldn’t find one. So he ventured, ‘my kid brother, he wrestles’ and I was 17 years old. I had wrestled amateur, Olympic-style, Greco-Roman style, but I had never wrestled professional. So he called me up on a Friday night and said ‘I’d like you to get on a plane tomorrow and start professional wrestling.’ And I said ‘whoa, I’ve never wrestling professional.’ He said, ‘that’s alright, you’ve wrestled Greco-Roman, and all that. You’ll do alright.’ So I got on the plane and wrestled that night.”

Rick won that first match in North Sydney, Nova Scotia. “I got a great feeling and loved it right away. And this is what I wanted to do. In fact, I did it for the summer and then I was supposed to go back to school in the fall. So I went back to school for one day and that night, I went to bed and I kept thinking, ‘wow man, I miss it already.’ The next day I went back to school and went to see the principal and I told him, this is it for me, I’m quitting. He said, ‘after one day?’ ‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘I know I’m not going to finish the year because I miss wrestling already. That’s what I want to do. This is it.’ My parents were shocked. And I went back into wrestling, and I never regretted it.”

As his brother had predicted many years before, the siblings would team on numerous occasions, especially in Stampede over the next few years.

But it is with Frenchy Martin as a tag team that Michel Martel is best remembered. The Mercenaries, with their black berets, were Frenchy’s idea, based out of the “Quebec shit” of the highly-politicized nationalist movement in la belle province. Billed as Michel and Pierre Martel, they worked for Montreal’s Grand Prix Wrestling and out in the Maritimes, feuding with The Beast & Rudy Kay and Leo Burke and a newcomer named Rod Piper.

They also worked in the IWA, run by Pedro Martinez and Eddie Einhorn, said Rick. “Michel and Frenchy went to work for these guys. But unfortunately, that didn’t work out. The problem, at that time, was the paperwork. For a while, he couldn’t get anybody to get him in contact, I’m talking about at the very beginning, to get a visa and stuff. He couldn’t get the right contacts, so it seemed, so he decided to go to Japan. He used to go to Japan quite a bit. Then Carlos (Colon) and Victor (Rivera) started in Puerto Rico, and he was real good friends with those guys. That’s when he concentrated on going there. He went to Puerto Rico quite a bit.”

Together, The Mercenaries traveled the world. “We did it happily. We had a good time. We were the same kind of people, the same spenders. Michel wasn’t close with his money, nor was I, nor am I,” said Martin.

Frenchy Martin’s career was really made in Puerto Rico, thanks to Michel. “He gave me a call that we could go to Puerto Rico together in ’75. We went down there and it was nothing but success because we popped the place right out. The Martel Brothers just kept on going a long time.”

In Puerto Rico, The Mercenaries worked against natives like Jose Rivera, Johnny Rivera, Carlos Colon, and foreign imports like the Moondogs. For a time, Michel’s old tag team partner in Stampede, Danny Babich, was brought in as a third Martel brother, Daniel.

From 1975 to 1978, The Mercenaries were regulars in Puerto Rico. Frenchy recalls those days very fondly. “We just knew each other, we just clicked together. There was no animosity, there was no, ‘Who’s the brain?’ No competition at all, compliments all the time. I complimented his ideas or if I came up with one, he’d put it aside and then later on, he’d come back and grab it and use it. … he was very intelligent. And naturally, when I was booking, I was very good too because I kind of followed his idea. In a way, we had the same mind, really. We didn’t have the same life, but we had the same mind.”

Rick Martel agrees with his ‘brother’ Frenchy Martin. “Michel was a great thinker of this business, angles and stuff. Him and Kroffat used to talk a lot about that stuff. He loved it. He loved that aspect of it, interviews. … I wish I could have had him as a manager. That would have been great.”

“I know, having been around him and now, with all the experience I have in this wrestling business, having been on both sides as a promoter and a booker and a wrestler, I know that Michel would have been a great asset for this business. His discipline and his ideas would have been great for the business. He was an innovator,” Martel said. “I remember him and I sitting for long hours talking about ideas, about different things. Of course, a lot of my ideas, a lot of the stuff that I later was able to lay down, in 1979, I was the booker in Hawaii. Michel had passed away in ’78, so when I took the book in Hawaii, a lot of what Michel taught me, I used a lot. At that time, I just 22 years old. I was directing men that were much older than me. But with the teaching of Michel, it helped me a great deal.”

It’s interesting, and very indicative of pro wrestling, that the details of Michel Martel’s death have remained hazy to both the wrestling community and the public for years. Some of the variations uncovered:

- He died in the ring, a victim of Invader #1’s (Jose Gonzales) heart punch.

- A botched knee drop ruptured his aorta.

- A broken rib punctured his heart.

- He passed out in the shower alone and was discovered by the cleaners and was rushed to the hospital.

None of these are correct, but the first version is important to make note of for two reasons. One, the heart punch was banned by the World Wrestling Council promotion to further publicize Invader #1 and continue the feud with Pierre Martel, and two, Gonzales was later accused of the dressing room murder of Bruiser Brody.

On Friday, June 30, 1978, Michel Martel was in Ponce, Puerto Rico, having been in the country for a couple of days, living it up with Pierre Martel and Jack Lafarb. The match that night at the hot and humid arena had Carlos Colon and Invaders 1 (Gonzales) and 2 (Roberto Soto) against The Mercenaries and Lafarb.

Dick Steinborn was at the show that night, and wrote about his memory of it on the Georgia Wrestling History Message Board. “There was so much action and fast moves that I believe they were all trying to outdo each with fast tags and a lot of high flying maneuvers,” he wrote.

Frenchy Martin said that Michel never complained about anything in the ring that night, but back in the dressing room, it was a different story. Their routine was to take a shower, sit on the bench for 10 minutes or so, then shower again in an attempt to deal with the incredible heat of Puerto Rico. “As we came back a second time, he said, ‘Jesus Christ, I thought I was going to fucking die.’ I said, ‘You’re fucking kidding.’ He said, ‘No, no. I thought I was going to die.’ I said, ‘Jesus Christ, let’s go to the hospital.’ He said, ‘No, no, I’m alright.’ So it stayed like that. ‘If you want, we go right away now after the shower.’ ‘No, no. I’m okay, but I really thought I was going to go.’ … no more than that, because we got hurt many times and everything is always alright the next day, so we never think about it.”

They got into the car to go back to San Juan, Puerto Rico. “All of a sudden, he says, ‘Stop the car, stop the car. I need to puke.’ He tried to puke, but nothing would come out. Then he got back in the car and the blue started coming to his mouth,” Martin said, his voice trembling and a shudder running through him. “Just a nightmare. The hospital was maybe five minutes from there and he didn’t make it.”

“He died in my hands, really. They took him into the hospital, they tried to re-animate him and they couldn’t do it.”

Rick Martel had spent some time with his brother in Quebec, and then they were in Georgia together for a brief while in the couple of months preceding June 30, 1978. Michel hadn’t been wrestling very often during that time period. “Wednesday night, [Michel] had just had a meeting with [WWC owner] Carlos [Colon] and called me up. I was supposed to go there later. He told me of the plans they had for him. He was very excited. Then the Friday, two days later, I received a call from Frenchy telling me that Michel had had an accident and to get on the plane as soon as possible. So I didn’t think of an accident (death), I thought of a car accident,” Martel said.

It was 3 a.m., and he began trying to work the phones for a reservation for the trip from Atlanta to Puerto Rico. He had no success, so he turned to promoter Jim Barnett, who had connections with Eastern Airlines. “He got me on a flight, even though it was full,” Martel said.

Next, he spoke with Frenchy Martin again to tell him about his flight details, which was leaving at 7 a.m. “When I called back and told Frenchy that I had the reservations, then I asked him, ‘Tell me, what is the accident? What happened?’ Then he told me that Michel was dead. That was quite a shock.”

Michel Martel was 33 years old, and his 21-year-old brother was now charged with the duty of bringing him home.

“Michel hadn’t worked much in the past few months. He went that night, apparently he ate before he went in the ring. I believe that’s what happened. I was told by Frenchy, and some of the guys who were there, he apparently ate just before he went in. Too late. When he went in, his main artery blocked and he suffocated,” said Martel.

Both Martel and Martin dismissed drugs and alcohol abuse as a contributing factor. “Michel liked to have a good time, he wasn’t like a partier every night to excess. First of all, there were no drugs at all. He was against drugs. I remember him telling me, ‘Don’t ever touch this.’ He was strictly a guy who liked to have a few drinks once in a while. He wasn’t a guy who would be by himself drinking. He’d be drinking if there was party going on with all the guys. He wasn’t the type of guy to drink every night,” said Martel. Martin concurs. “A couple of drinks, and that was it. In the team, I was the drinker, according to the people who know.”

The plane arrived in San Juan with Martel on it early on Saturday morning. He tried to call Frenchy on the number he had, and it wouldn’t work. Then he tried the WWC office, which was closed. Martel didn’t know Spanish and tried Frenchy and the WWC office again and again throughout the day. Having been up more than 24 hours, Martel decided to get a hotel room and asked the clerk to wake him every hour so he could try to call again. Still nothing.

Sunday morning, he went to the police and explained his case. “I said, ‘Look, I’m a wrestler, my brother’s dead, I don’t know who to contact.’ One guy says, ‘I think I know where some wrestlers live, in an apartment building.’ Sure enough, lucky for me, it was the right building where Frenchy and Michel had their apartment.” The caretaker opened the door. “We walked in with the police, and Frenchy was under the kitchen table, lying there, just sleeping there.”

Hugo Savanovich, who was staying with Frenchy during the ordeal, came out of the bedroom, and said, “Man, Rick, what’s going on? We’ve been waiting for your call all night. Frenchy didn’t want to move from that table until you called.”

Frenchy had sat at the table, having drink after drink, awaiting Rick’s call. “When Michel died, I just drank myself to death. I was in the closet when he came in. It was terrible. I was so close, then boom. Life is like that,” said Martin.

Martel went with Carlos Colon to identify his brother’s body in Ponce. “You should have seen the hospital where he was. Unbelievable. Unreal. … First off, I was in shock from the whole thing. Then when I walked into this hospital and they opened the freezer where he was, to get him out of there, it was like a thing for veterinarians. I couldn’t believe where they had him. And also, when they got him embalmed, he was all white … it was horrible. We had to have people work him over a little bit before my mom saw him.”

The coroner’s report came later in the mail, written in Spanish. “Frenchy translated it. I didn’t really have any confidence in what they said, so I just let it go. I was in shock even for years after, especially weeks after,” Martel said.

Having done the necessary paperwork to get his brother home, Rick arranged for a tiring series of flights home-San Juan, Puerto Rico to Philadelphia, Philadelphia to Montreal, Montreal to Quebec City.

It didn’t work out as planned, said Martel. “I get into Quebec City. We’re waiting for Michel. The Eastern Airlines people come to me, ‘Mr. Vigneault/Martel, your brother is still in Philadelphia. We didn’t have time to switch him planes.’ Now my family is there, the funeral home people are there. ‘He’s still in Philadelphia. Tomorrow morning at 10 o’clock he’ll be in.'”

The funeral home agreed to return the next day to pick up the coffin. “A guy calls me up at 10 o’clock that morning from the airport and says, ‘He’s not on the plane.’ I said, ‘What?’ I called Eastern. Eastern said they sent him to … Delta. ‘We sent him to Delta.’ I called Delta, and Delta had no records of him. So my mom was going crazy. They lost him for a while. It took all afternoon before finally he arrived in Montreal. The guy called me from Montreal, 4 o’clock in the afternoon. ‘Okay, he’s finally here. He’s going to be there at 7.’ What a weekend that was!”

The funeral was held in Quebec City, and Frenchy Martin, Mad Dog Vachon and a host of other local wrestlers were in attendance. “For several months after I was on the road, a lot of people got in touch with me, a lot guys that knew Michel called me up, gave me their sympathy. He was well liked. Michel had a good reputation,” Martel said.

Longtime Stampede Wrestling promoter and photographer Bob Leonard recalled how the promotion dealt with Michel Martel’s death. “We were good friends during his many months here over the years, and it was a really hard jolt when I heard of his sudden passing. I was on the loop that week, and Stu asked me to deliver the news and do the ten-bell for him each night,” he said. “That, of course, was before death became such a regular visitor to the business, and I felt some very genuine shock and sadness in all the arenas as the people here knew him so well and had a great measure of respect for him, and I feel always really liked Michel whether he was working heel or face.”

In Quebec City, Rick was determined to keep wrestling. “My mom and my family, with me having to go back on the road after that was pretty touchy. My mom didn’t want me to keep wrestling after that,” Martel said. “But I made her understand that Michel did so much to get me into wrestling, that the last thing he wanted me to do was to quit. It’s an accident, just like in any kind of sport or drive a car. … after a few weeks, I was able to go back.”

His brother had taught him well. “There wasn’t one move I wouldn’t do before calling him,” Rick said. “When I left Georgia or Texas, I said, ‘Michel, what do you think I should do? Should I go there?’ ‘Oh yeah, do this.’ … The one thing that Michel did that really helped me a lot, and in fact when he died, I was able to deal myself with promoters. I remember my first ever long distance call I made to a promoter. It was Stu Hart, and Michel was right beside me. … He got me confidence in dealing with promoters right off the start. So that helped me a great deal because, as you know, I was 21 years old. When he left, I still had the confidence in me. It’s not like I lost somebody that spoke for me and now I couldn’t handle it. He passed on some great value to me.”

As with the death of anyone so young, there is much question of what could have been. “I think Michel was just about to crack the nut. I think he would have made a tremendous manager or a wrestler-manager. In fact, I have a tape here of him that I picked up from his personal affairs from his apartment in Puerto Rico. He had laid out this program, this six-month program,” Rick said.

Once he returned to Puerto Rico, Martin never questioned the use of the tragedy in the storyline. “We were right in a big program and we were drawing money, so naturally, that’s wrestling. … In wrestling, they take every opportunity they have to make a dollar,” he said. “Gonzales, he just took the gravy out of it, he didn’t push the boat, he just got on the boat when it was going. Bad luck happened and that’s what made him”

Thrust further into the headlines in Puerto Rico and deeper into a feud with Invader #1 that would last years, Frenchy Martin believes The Mercenaries could have gone further than Puerto Rico. “We would have gone to the top. … We were THE team then. Jesus Christ, everything just clicked, everything was so perfect. … no pulling on either side. … never any arguments, which is what destroyed teams all the time, when one was torturing the other, which was not the case with us. We were good friends when we went there, and when we came out of there.”