‘Playboy’ Gary Hart, one of the most hated managers of the past 30 years, is finding out that he’s not so hated after all. Only in wrestling could a man be booed and cursed for almost all of his 40-year career and find newfound respect from the fans at the end of it all.

A while back, Hart was on the radio for two hours promoting a charity show that he was running in Texas. “People were calling in and talking about wrestling and not one person, not one person said a derogatory thing about me,” Hart told SLAM! Wrestling. “The next evening, Gentleman Chris Adams and Kevin von Erich were on the show. It sounded like they were the bad guys. People were calling in and saying horrible stuff to them. So I told my kid, I guess I failed as a bad guy. I should have been a good guy, then they would have ended up hating me!”

Of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Hart WAS a very hated man, with some of the most imposing stables of wrestlers ever assembled. He was of the belief that there was no point in just managing one wrestler in a territory – you may as well manage a whole bunch.

“I usually had a crew of five guys that I kept with me, that way you could control the town. I learned from Buddy Rogers that ‘he who surrounded himself with the best talent controlled the town,'” Hart said.

He sighs now when asked to remember who he managed. Hart started with Angelo Poffo, then went on to, in no particular order, George ‘The Animal’ Steele, The Kangaroos (Al Costello, and Karl von Brauner), The Missouri Mauler, Brute Bernard, ‘The Spoiler ‘ Don Jardine, Mark Lewin, Curtis Iaukea, the Great Kabuki, the Great Muta, Bob Orton Jr., Dicky Slater, Buzz Sawyer, Bruiser Brody, Gino Hernandez. In all, Hart guesses that he managed probably 25-30 wrestlers during his career. “My deal was that I always had four or five guys with me, and we would do what was best for the town and ourselves.”

The 59-year-old Hart started in pro wrestling in 1960, but had been interested in it for years before. His uncle, Billy Gales, was the booking agent for Fred Kohler in the Chicago area. One night, Angelo Poffo was looking for someone to be a second to him, as Bronko Lubbich had gone to the Carolinas. “I started as his second. As time went by, he liked me, I became his tag team partner, then I became his manager.”

Hart looks back fondly now on all the time he spent with his uncle. “I would go to the Marigold on Saturday mornings with my uncle, then on Wednesday mornings with my uncle, and I’d beg him to get in the ring and work out with me. So I started when I was only 18 years old, but I had been trained since I was 15.”

After starting in Chicago, Hart went to Detroit where he worked under Bert Ruby until The Sheik Ed Farhat took over the territory. “[The Sheik] was really cheap, man. That’s why I left. You could sell out the Cobo Arena, and he would give you $300. And I would sell out the Sam Houston Coliseum, and I’d get $1,000. So I knew that every time I worked Detroit, I was losing $700.”

But The Original Sheik wasn’t all that bad. “I liked him a lot. I think he was a great guy. But he’s the type of guy that would buy you a $100 dinner, and a $50 payoff. So I didn’t really care for the way he paid, so I didn’t spend a great amount of time with him. My thing was, if I filled up your building, and you didn’t pay me, my boys would leave. Because in those days, if you had a good crew with you, there were always promoters. Some place would be down. If Texas was hot, Florida would be down, if Florida was hot, Georgia would be down. There was always a promoter that needed someone to fill up his arena. That was the part of the business that I was best at. I knew how to get talent over, I knew how to take empty buildings and make them full.”

True to his philosophy, Hart packed up and went to Texas where Morris Siegel was getting ready to get out of the wrestling business, and Ed McLamore was taking it over. Hart was approached to bring some talent in. Following his uncle’s footsteps, Hart got involved in the booking of talent which led to meeting Jim Barnett, who controlled Australia, Atlanta and Florida.

Hart worked off-and-on in Australia for seven years, coming back and forth to Texas. “Australia was an ethnic country for wrestling,” Hart explained. “You had a guy like Spiros Arion who was a Greek, and you needed a Greek. You had Mario Milano, Dominic DeNucci, Tony Pugliese at different times as the Italian wrestlers. A few Americans were the fan favourites, but mainly it was the ethnic groups.”

In Australia, Hart became great friends with Brute Bernard, Skull Murphy, Tony Parisi, Dick ‘The Bulldog’ Brower, and The Spoiler Don Jardine. In fact, he made many friends. “I had a good rapport with all my guys. I was very selective. I wouldn’t take a guy unless I really got along with him really, really good. I was a primadonna when it came to guys who I would manage. I can’t really think of anyone, even to this day, that I was with that we weren’t good friends, and still don’t have a good rapport with. I didn’t have any of those ‘I hate you’ type things.”

Besides managing, Hart is best known for helping to make Dusty Rhodes the star that he was. Rhodes had just left football and he came to Dallas wanting to start wrestling. Hart helped him get booked, knew that he had some talent. “He had fantastic charisma, and I told him the name Virgil Runnels wasn’t very good,” he remembered with a laugh.

Hart had just watched the Andy Griffith move A Face In The Crowd, and one of the characters’ name was Lonesome Rhodes and something just clicked.

Rhodes was in Texas with Hart for about half a year, and then was sent to Kansas City and Australia for a year. “Then he went to Florida and became a big heel. I came into Florida with a guy named Pak Song Nam, a big Korean. And Dusty switched then, and I named him The American Dream. We did capacity business in Florida for 26 weeks in a row, he sold out every arena that he appeared in. … I’m more proud of what he accomplished than anything else.”

In the Carolinas, Hart went to work for the Crocketts. “I really worked for only four offices. I didn’t work for a lot of places.”

He spent less than a year in the NWA. “I said this isn’t going to work. I was on tour for 50, 55 days at a time. It just had a full cup. I had had enough. It just was no fun for me no more. I said that when this thing becomes like a job to me, I ain’t interested in doing it no more on that scale.”

Hart remembers quite clearly was he was doing when he heard about the sale of the NWA to Ted Turner. “We were doing $100,000 a night with Jimmy Crockett. He had a G1 that took 15 of us, and he had a Lear jet that sat 10 of us. One day they came on the G1 and said ‘Great news! Ted Turner’s buying the business.’ I looked at Al Perez and Dusty Rhodes and said ‘This is the worst f***ing thing that could possibly happen.’ And within six months, they proved me right.”

It was the arrival of corporate wrestling, and it changed everything. “Before, if you didn’t draw money, if you didn’t fill the seats in the arena, you had no power. When corporate wrestling got involved, and people that had no knowledge of what it took to manipulate talent, develop talent and sell out buildings. They look at a guy and go, ‘Hey I like the way he looks, I like his outfits. Let’s give him a name.’ A person that really that had a background, that had some experience with how to do these things, that’s why Vince is so successful, because him, Gerry Brisco, Pat Patterson, Sgt. Slaughter, Tony Garea. All these guys, they can watch you walk to the ring and know if you’re capable or not. That’s why Vince is successful. The reason that Atlanta isn’t successful is if you know what’s going on, they don’t want you around.”

Hart considers himself a pretty good judge of talent too, and has been training the youngest of his two sons, Chad, for a career in pro wrestling. He sees nothing but good things ahead. “Judging talent the way that I judge talent, he has been trained properly. I think that he has an excellent shot. He understands modern-day wrestling, he understands everything that you need to know to make it in big-time wrestling.”

Chad Hart 198 pounds now, and his father things that he needs to add another 20 pounds before he can have a shot. But on the indy shows “he steals the show every time” says dad.

Like his father, Chad started wrestling young, at 17. Now 21, he’s listening and learning from the veteran. “I’m molding his mind to accept the corporate way. I had been in wrestling for 30-some years when I went corporate,” said Gary Hart. “If you don’t know what was before … I had control. I could go to a promoter and say, ‘Look, I can bring you five guys. I can make your town draw money.’ So if I could, in fact, do that, then I had the power. But when you got into corporate wrestling, they didn’t care. They didn’t care if the box office was slush or not. They wanted to do what they wanted to do. And when you don’t have the power of persuasion, then you have no power at all. I just couldn’t see myself, after all the years of getting my way, and that sounds selfish I know — getting my way meant making money for me, the town and my boys.

“Chad, I have told him that wrestling is not what it used to be. It’s not a serious sport, it’s more of a show today. That’s the way I have groomed him. I want him to understand what he’s going into. But I have no problems with him doing it.”

In fact, Hart himself is still involved on occasion with pro wrestling, running a few fundraising shows for organizations like the food bank or women’s shelters. After running the much bigger Sportatorium and Metro Plex facilities for a couple of years, he’s enjoying the smaller scale shows. “I’m happier this way. I do it when I want to.”

Of course, his head is still bald and after more than 20 years on TV, he’s still recognized almost everywhere he goes. “It’s pretty hard to go some place where people don’t say, ‘Hey, you’re Gary Hart.'”

But despite the continuing celebrity, Hart insists that he wouldn’t go work for Vince McMahon and the WWF if they called tomorrow. “Hey man, I’m 59 years old. But if wanted my son, I’d put him on a plane immediately, tell Chad to keep his mouth shut and do what Vince asks.”

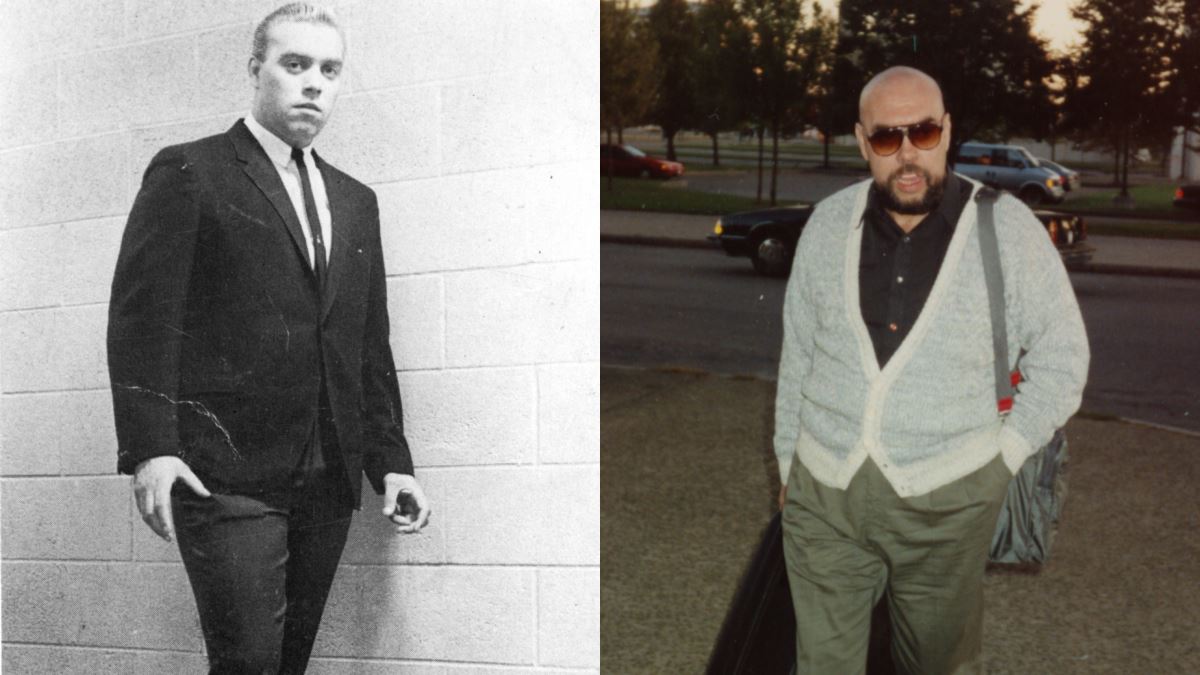

TOP PHOTOS: Left, Gary Hart in 1960; right, Gary Hart in 1989 by Terry Dart.

RELATED LINKS

- Oct. 27, 2009: Posthumous Gary Hart autobiography one of the best ever

- Oct. 21, 2009: Help from friends and family got Gary Hart’s book to market

- Oct. 28, 2008: Gary Hart Guest Booker DVD a bittersweet masterpiece

- Mar. 17. 2008: Gary Hart: ‘With a little help from my friends’

- Mar. 17, 2008: Manager/booker Gary Hart dies