It was 1968 in Eastern Europe, and Soviet tanks were crushing the Prague Spring reform movement. Individual freedom was virtually unknown. Repression against students and dissidents everywhere was commonplace, and advocates of democratization landed in jail, if they lived at all.

Josip Nikolai Peruzovic, an elite teenage weightlifter and wrestler of Russian and Croatian blood, had seen enough. So the young man made a fateful and solitary decision. When his Yugoslavian weightlifting team prepared to return home after an international competition in Austria, Peruzovic balked.

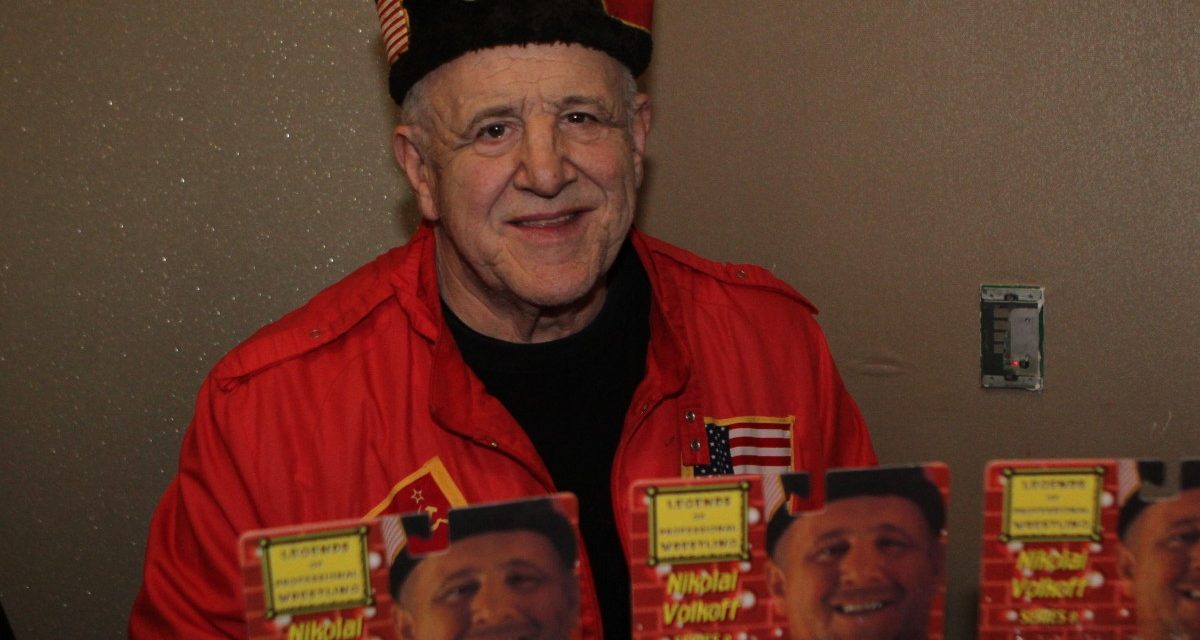

Nikolai Volkoff (left, seated) was a top heel in the WWWF for two decades. (Photo: Steven Johnson, SLAM! Wrestling)

And then he was gone for good.

Thirty-five years later, Peruzovic is telling this story softly, in heavily accented English — how he left Yugoslavia and his family to defect to the West without benefit of the English language or money. He speaks matter-of-factly as he describes the conditions that caused him to flee, and only at one point does a trace of anger creep into his voice.

“Those communist bastards,” he said. “I hated them.”

* * *

Even in the bizarre world of professional wrestling, it sounds curious to hear a bitter denunciation of communism from Peruzovic, better known to the wrestling community as Nikolai Volkoff.

As a monstrous villain from Russia, Volkoff was a headliner against the likes of Bruno Sammartino, Gorilla Monsoon, and Hulk Hogan in the WWWF and elsewhere for most of the 1970s and 1980s.

To his legions of friends and family, though, Volkoff is neither monstrous nor a villain. Nor is he from Russia, though he speaks the language and his mother is Russian.

In fact, he was just an emigre hoping to turn his amateur wrestling background into work when he landed in Calgary after his defection to train with the legendary Stu Hart.

At 300-plus pounds of rock-hard muscle, Volkoff had size, athletic ability, and great bloodlines — he was trained by his grandfather, a one-time bodyguard for Austrian monarch Franz Josef.

But he had no real expectations, and his cover story, to protect his parents from possible harassment at home, was that he was merely traveling and would return to defend his country’s honor in event of a war.

“I was just so happy to get out from there,” said Volkoff, who chose Canada as his destination because it processed immigrants quickly. “Here, with freedom, you can say what you think. There, they go behind your back, and the next thing you know, you’re going to Siberia to cool off for the rest of your life.”

Working with Hart, Volkoff quickly caught the attention of Newton Tattrie, aka Geeto Mongol, who wanted a partner for a tag team idea that occurred to him while he was browsing through books at a Calgary library.

With their partially shaved heads and fearsome visage, the Mongols — Volkoff was called “Bepo,” a term of endearment from his mother — were an instant in-ring success.

The food and the language — that was another matter.

“Man, I could not eat any food,” he recalled. “Chicken, meat, oh, it tasted terrible. From where I came from, it’s all natural food, you kill a cow and eat the same day because there was no refrigeration. It’s all nice and fresh. When I came here, I could not eat.”

And what he could take in was severely limited by the communications barrier.

During their time in Montreal, Geeto, his restaurant interpreter, had to leave his young charge alone for a few days. Before he left, he taught him “When you’re hungry, ‘apple pie and coffee,'” and that’s what Bepo ordered for several meals.

After a few days, he grew weary of the same bland diet and spotted a woman nearby eating a tasty hamburger steak. Bepo looked at the waitress and pointed to the woman and her meal.

“What is it you want, then?” the waitress asked.

He kept pointing, grunting, and gesticulating toward the steak to no avail. Finally, he abandoned hope. “Apple pie and coffee,” he told the waitress.

After prepping in Montreal, the Mongols invaded the WWWF in 1970 after a carefully planned, three-month program of television exposure. “He caught on pretty quick. He was a good athlete and he was in good shape. He was very easy to train,” Geeto said.

The Mongols captured the International tag championship, the highest WWWF tag belts at the time, from Victor Rivera and Tony Marino in June 1970. They held them for a solid year, an eternity by today’s standards, and enjoyed another four-month reign in the late summer of 1971.

With that success as a Mongol, Bepo understandably recoiled at being packaged as a ruthless, methodical Soviet destruction machine when the Volkoff persona arose in 1974.

But the legendary Freddie Blassie, who was retiring to become a manager, persuaded him that aggrandizing the Soviet system could actually serve Volkoff’s anti-Soviet ends.

“He told me, ‘The more you say about that, people are going to hate you more.’ I said, ‘But I hate Communism.’ ”

Responded Blassie: “Then if you hate Communism, that’s how you destroy it. Tell people how good it is over there, so they know you’re lying.”

Volkoff followed his manager’s advice and became the wrestling caricature of a Soviet tool for more than 15 years.

“If you say something truthful, there is no heat. Nobody cares,” he said.

“But if you say, ‘In Russia, people buy cars only until the style wears out, then they drive it right to the junkyard to be melted down for military purposes,’ then people know you are lying. Then you get the heat and the people say, ‘That is ridiculous!'”

Volkoff established himself as a major player for years to come in March 1974 when he battled to a one-hour draw with WWWF champion Bruno Sammartino at Madison Square Garden.

The match set a gate record for the famous arena and the duo continued their feud up and down the East Coast for years. Blessed with long fingers and a vise-like grip, Volkoff could crush an apple with one hand — on televised interviews, he said the apple represented what he planned to do to Sammartino.

In reality, his admiration for Sammartino knows no bounds. “He was the greatest,” Volkoff said. “He was the greatest wrestler who ever lived.”

Volkoff also had successful runs in the Southern U.S. and Japan, holding the NWA Mid-Atlantic tag title with Chris Markoff and the NWA Georgia Heavyweight title.

In 1983-84, he started using an ingenious gimmick developed by promoter Bill Watts. Before his matches, Volkoff insisted fans stand and respectfully observe the singing of the Soviet national anthem.

When he re-entered the WWF in 1984, frequently teaming with the Iron Sheik, a former WWF champion, Volkoff continued to belt out the Soviet anthem before each match.

With Blassie earnestly standing by, hand on heart, and the hated Iron Sheik in the ring, Volkoff’s vocals attracted enough debris from irate fans that Monsoon once commented, “There’s no need for a food drive when this guy starts to sing.”

“Oh, the heat that drew,” Volkoff remembered. “It was unbelievable. People hated me and they hated Russia. So that worked.”

At WrestleMania I in 1985, Volkoff teamed with the Iron Sheik to beat Barry Windham and Mike Rotundo for the tag team championship he had first held with Geeto 15 years before.

He later paired with Boris Zhukov as The Bolsheviks, a thoroughly despicable pair of Soviet sympathizers that was a fixture on television, pay-per-views, and house shows from 1987 to 1990.

On a televised Superstars of Wrestling show in the spring of 1990, Zhukov entered the ring first and delivered an indifferent version of the Soviet anthem. As Volkoff grabbed the microphone, he pledged to show Zhukov how to sing properly.

To stunned fans, Volkoff launched into a stirring rendition of The Star Spangled Banner to wild applause, setting up a feud with Zhukov and cementing one of the most memorable turns in years.

Ironically, political developments in Eastern Europe, which once sent Volkoff fleeing for the West, facilitated his transition to wrestling hero.

The Berlin Wall fell in 1989. Reformers in Poland and Czechoslovakia drove communist leaders from power. The Balkan republics started to declare their independence from Russia, and, in 1991, Soviet communism collapsed.

And Volkoff joyously ended his days as a staunch Russian heel.

“When Russia fell down, I said, ‘That is enough for me. There’s no more reason for me to be a bad guy. I don’t have a reason to be a bad guy.’ Communism was gone and I was so happy,” he said.

Volkoff did a final stint with the WWF in 1994-95 as part of “Million Dollar Man” Ted DiBiase’s stable, and still occasionally wrestles on weekends. He also has started his own one-man show on stage called ‘An Evening With Nikolai Volkoff’, sharing the story of his escape from Communism. He also performs magic tricks and sings.

As his career wound down, he became one civil servant that no one wanted to anger, as a code enforcement inspector in Baltimore County. He lives on a sprawling, 50-acre farm near Baltimore with Lynn, his wife of 33 years, and looks back fondly on his long and amazing journey.

“When Russia was in power, I did everything I could to make them look bad. Then one day, Russia was gone, and I said, ‘My job is done.'”

RELATED LINK