I’m on a bit of a heel kick lately. Last time out I wrote about my preference for complex villains, especially those who rightly or wrongly see themselves as the heroes of their lives.

Pure evil generally holds less interest.

Very few people are so misanthropic that they walk around congratulating themselves on their badness, like Beastly, the henchmonster in the 1980s Care Bears cartoon, whose catch phrase was literally “Ooooooh, I’m sooooo bad.” Care Bears featured a main villain named No-Heart. I hoped he would prevail. I feel the same way about He-Man’s nemesis Skeletor, who opined during a Christmas special that he “doesn’t want to feel good, [he] wants to feel evil.” I use that line on Zoom calls at work. I also sometimes set my background to Castle Greyskull. Do with that what you will.

There are exceptions to every rule — and if heels do anything well it’s capitalizing on those exceptions. One of my all-time favorite heels was evil personified. It’s been a rough few weeks for bad guys. Kevin Sullivan passed away on August 9. There are far better obituaries and tributes out there, but for me Sullivan still stands out as the embodiment of actual wrestling evil. Sullivan started wrestling in 1970. He cycled through a series of heel and face turns and experimented with different gimmicks until he found something that worked.

In 1982 Sullivan joined Championship Wrestling from Florida and became wrestling’s preeminent face of fear. It was a savvy move. He rechristened himself the “Prince of Darkness” and played an occult-loving cult leader. Although Sullivan never outright claimed to be in league with the Devil, he regularly invoked dark spirits. He incorporated arcane symbols and mystical mumbo-jumbo into his persona, and at times added leather and spikes to his gear, much like Judas Priest’s Rob Halford (Clive Barker would make those outfits a central part of his mid-1980s Hellraiser series. Both men acknowledged they only mainstreamed a look common in London’s underground Gay club scene).

Sullivan’s brand of evil drew heavily from the so-called “Satanic Panic”, a widespread fear that devil worship and its associated depravities and abuses had gained a foothold in American society. In real life the Satanic Panic involved more than 10,000 cases of unsubstantiated ritual abuse. The panic persists to this day. It has largely been discredited as it was associated with debunked para-psychology concepts like recovered memory therapy. Claims associated with the Satanic Panic often included accounts of physical or sexual abuse as part of occult or Satanic rituals. Proponents still fold their allegations into vast conspiracy theories, alleging the existence of a global cult comprised of wealthy elites who commit atrocities against people, especially children. The Satanic Panic arguably grew out of trends in popular culture: movies like Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist and The Omen had captured the public’s imagination in the previous decade. Charles Manson emerged as a real-life monster, directing his cult members to murder. Working mostly in Southern states like Florida, where many wrestling fans were also Evangelical Christians, the intent behind Sullivan’s character was clear — even if it was lost on me as a grade schooler in Toronto. All I knew was that Sullivan was evil and, rare for wrestling, scary.

To capitalize on these associations Sullivan grew out his hair and beard and painted his face. He drew disaffected wrestlers to him including Mark Lewin as the Purple Haze and Bob Roop. Sullivan’s stable also included female talent like the Lock (Wenona Little Heart), Luna Vachon, Dark Journey and Fallen Angel (his real-life then-wife, Nancy). It was a main event gimmick that pitted Sullivan against Dusty Rhodes for years.

Sullivan moved on to Jim Crockett Promotions/World Championship Wrestling in 1987 and apart from a sojourn from 1992 to 1994 stayed on until the promotion died. He started off as the wrestler-manager of the Varsity Club stable, which at various times included Rick Steiner, Mike Rotunda, Steve Williams and Dan Spivey, a pretty impressive list of names. Sullivan was pitched as a sinister force who guided these men — especially Rotunda, who developed a thousand-yard stare and a mean streak to match after years playing a babyface. The nature of Sullivan’s control over a group of grown men reverting to their university days as heels was never clear. Maybe it was just meant to combine credibility with creepiness, since the Club’s angles often involved Sullivan’s crushes on valets.

When the Varsity Club ended Sullivan went crazier and formed the Slaughterhouse stable, which featured a revolving door of talent including Cactus Jack, Buzz Sawyer, Bam Bam Bigelow, One Man Gang, Black Blood (Billy Jack Haynes, who is scarier in real life as it turns out), Tony Atlas, the Barbarian and the Angel of Death.

Sullivan’s goofier WCW persona reflected the need to reach a broader, younger audience. It also showed some of Sullivan’s creative range. If Sullivan drew from a real life, adult moral panic for his Florida incarnation, he went full kiddie villain with WCW.

When Hulk Hogan joined WCW in 1994 Sullivan perceived the need for a broad villain to counter Hogan’s super-heroic shtick. Sullivan created the Three Faces of Fear and later the Dungeon of Doom; borrowing existing monster heels and repackaging them as he saw fit with almost childishly simple, instantly recognizable bad guy gimmicks. My favorite part of the act involved Sullivan’s interactions with King Curtis Iaukea, renamed the Master and covered in baby powder. Iaukea bellowed and growled and called “SULLIVAN, MY SON.” I do the same today, and neither of my children are named Sullivan.

If you grew up with the Prince of Darkness, this felt like a silly walk backwards. It didn’t help that the grade schoolers who feared Sullivan would have grown into surly, disbelieving teenagers, and many would leave pro wrestling entirely until Hogan turned heel a few years later. Sullivan knew what he was doing. Casting himself as the stable’s leader brought him into Hogan’s orbit without demanding a one-on-one match, the optics of which would have made the outcome obvious. Playing up the magic allowed for lapses in continuity and admitted a bizarre range of bad guys that included serious contenders like Lex Luger, Vader, and The Giant (who would win the WCW championship), supporting characters like Hugh Morris, Meng and the Barbarian, Big Bubba Rogers, the One Man Gang and John Tenta, continuity with Jimmy Hart and Brutus Beefcake, and freakshow digressions like Loch Ness, the Yeti, Tiny “Z Gangsta” Lister, and Jeep Swenson as the unfortunately named Ultimate Solution. I still don’t know where Konnan fit into the plan.

Sullivan has stated this was all intentional. When he looked at blond, muscular, one dimensional hero Hogan he saw He-Man from the recently-aired Masters of the Universe cartoons. I missed it at the time, but Sullivan in his robes and new facepaint that looked like empty eye sockets and inept rogues gallery of henchmen was channeling He-Man’s adversary, Skeletor. Zodiac. Shark. Taskmaster. Loch Ness. Yeti. Meet Beast Man, Mer Man, Trap Jaw, Stinkor and Tri-Klops. In hindsight it’s brilliant. And hilarious. And the best kind of wrestling foolishness.

Sullivan never won a world title, but I can’t think of many who carried extended feuds with two of wrestling’s most popular good guys — Dusty and Hogan, or who pulled off a strangely compelling feud between heel factions when the Dungeon of Doom turned on Ric Flair and the Four Horsemen (which would have far reaching professional and personal consequences for Sullivan and others).

Sullivan worked through 2021 on the independent scene, spreading darkness wherever he went. Sullivan had a brief run in Ring of Honor where he tried to convince babyface Steve Corino to reclaim his heel nature. He did shoot interviews and panels and signed autographs and gave fans a glimpse of the good guy who played the bad guy. One of his last appearances came in an NSFW video he shot in 2023 with Karrion Kross. In this vignette Sullivan appears as Kross’ mentor, transitioning to the role that Iaukea once played. You can see his influence over Kross’ current harbinger-of-the-apocalypse gimmick alongside wife Scarlett Bordeaux’s tarot cards and tacit Biblical references in the Final Testament. Ditto for Raven’s various stables from the 1990s through the 2010s. More recently, the Wyatt Family (and now the Wyatt Sicks) borrows heavily from Sullivan’s approach to management. AEW’s offshoot the Dark Order traded overt evil for a more corporate kind of menace, while Malakai Black has put occult references (and some truly badass Black Metal music) at the center of his House of Black stable. At this point any character who identifies as evil owes Sullivan a debt of gratitude — though they may already have struck a Faustian bargain for his approval.

I have often wondered why Sullivan never caught on with WWE. He spent three years in the WWWF early in his career, as a lower-to-mid card babyface (believe it or not). Jim Ross claimed that Sullivan’s Satanic 1980s gimmick was too evil for Vince McMahon’s cartoonish view of pro wrestling, although Sullivan disputed this. Maybe WWE’s preference for giants, monsters and bodybuilders left him on the outside-although the WWF could have used him as a manager following failed attempts with the likes of John “Coach” Tolos, Curtis “The Wizard” Iaukea (who would go on to work with Sullivan in WCW as part of the Dungeon of Doom) and even more briefly, Baron von Raschke as “The Baron” (to say nothing of the Iron Sheik or Honky Tonk Man’s managerial exploits). Maybe it was Sullivan’s thick Boston accent — out of place for a man who claimed to hail from Singapore and a promotion determined to go national. Even if Sullivan had no place in front of WWE TV cameras you’d think he would have been an asset to the writer’s room. Behind the scenes Sullivan seems to have been respected and liked.

It’s one thing to write about evil in pro wrestling terms. After all, it’s an unwritten rule in most genres (and was actually a written rule under the Comics Code of Authority, which set decency standards for superhero yarns for decades) that ‘good’ always triumphs over ‘evil’.

Here in real life, ‘good’ and ‘evil’ seem to have become much more malleable of late, and the enjoyment I took out of morally relativistic ‘villains’ convinced they’re on the side of right rings hollow when I watch the evening news.

How ironic that Sullivan’s brand of evil now feels safe in its directness.

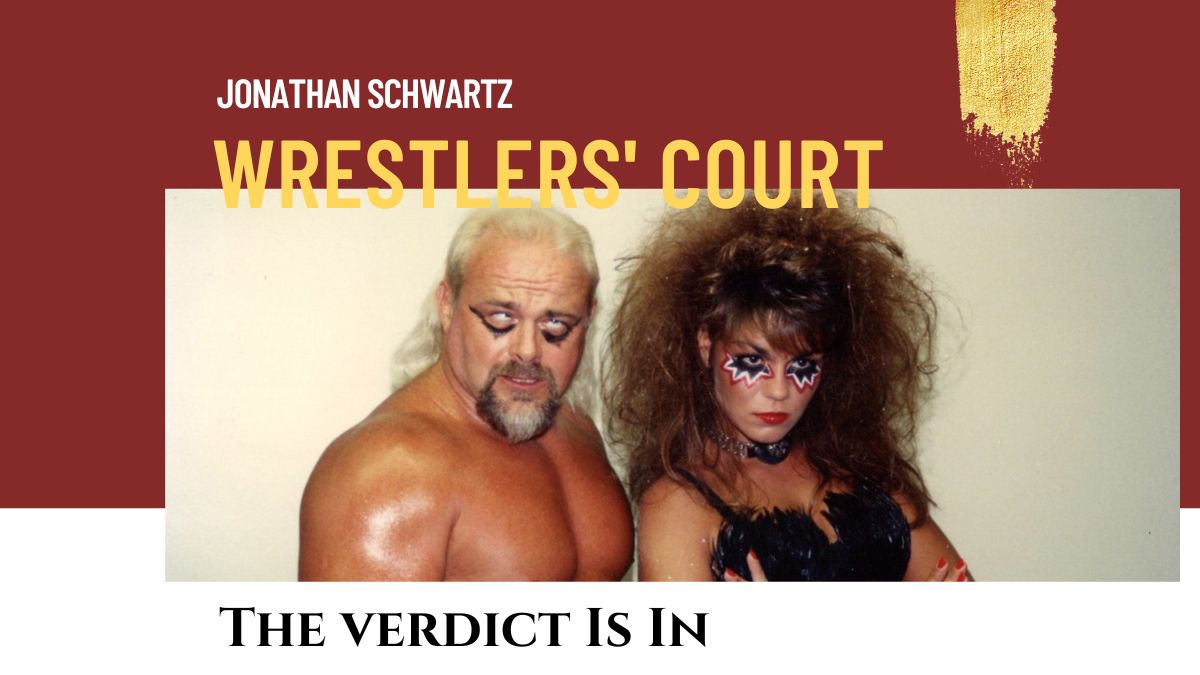

TOP PHOTO: Kevin Sullivan and Woman (Nancy Sullivan). Photo by George Tahinos, https://georgetahinos.smugmug.com

RELATED LINK